West Africa: Silk Roads and Denim Highways

By Lieutenant Colonel Johnny Wandasan, U.S. Army; Commander Andrew Davis, U.S. Navy; Lieutenant Commander Bryan Kilcoin, U..S. Coast Guard; and Major Branndon Teffeteller, U.S. Air Force

Editor's note: This thesis won the FAO Association writing award at the Joint and Combined Warfare School, Joint Forces Staff College. The Journal is pleased to bring you this outstanding scholarship.

Disclaimer: The contents of this submission reflect our writing team’s original views and are not necessarily endorsed by the Joint Forces Staff College or the Department of Defense.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in West Africa is part of a broader effort to reshape the economic world order to suit Beijing’s aspirations for Great Power status. BRI activities directly compete with the U.S. national interest of being the African continent’s partner nation of choice. The 2017 National Security Strategy warns:

China is expanding its economic and military presence in Africa, growing from a small investor in the continent two decades ago into Africa’s largest trading partner today. Some Chinese practices undermine Africa’s long-term development by corrupting elites, dominating extractive industries, and locking countries into unsustainable and opaque debts and commitments.1

The 2019 United States Africa Command (USAFRICOM) Posture Statement raised specific concerns over China’s presence across the continent. Marine Corps General Thomas D. Waldhauser highlighted China’s considerable investments across Africa, including loans to countries in strategic locations, such as Djibouti, Sen egal, and Angola.2 Through the BRI, African nation signatories receive assurances of investments in infrastructure, defense, and cultural development, which expands Beijing’s influence, and complicates U.S. partnerships in the region.3 To effectively engage in great power

competition (GPC) with China’s BRI in West Africa, USAFRICOM needs a focused, resourced approach that is synchronized with and supported by U.S. policy.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative is expanding across Africa.

China continues to strategically utilize instruments of national power to gain status on the global stage. Most notable is the application of the economic lever of national power through the BRI. China’s BRI is a trillion-dollar program4 designed to link the economies in Asia, Europe, and Africa through various land and sea routes. China has been investing in Africa’s infrastructure for decades. However, there is concern about the legitimacy of China’s efforts to strengthen ties through development of African markets on mutually beneficial terms. China’s broad approach to unilateral investments – often bereft of transparency and accountability – and use of memorandums of understanding (MOUs)5 harbor concerns that China is utilizing predatory investment practices that take advantage of loan defaults. These MOUs reflect China’s growing in fluence across the continent, and the potential for expansion of Beijing’s power projection via access to Africa’s ports.

Africa’s economic growth depends on infrastructure development, especially projects that involve port expansion. Over ninety percent of African exports depend on ports.6 An effort that stems from BRI is the Port-Park-City (PPC) model, featuring mega logistics projects at major ports that are funded, built, or operated (often a combination of these) by China. These upgrades enhance the ability of these ports to become trading hubs, increasing the viability of trade routes along Africa’s coast. These hubs, or industrial parks, have the potential to include special economic or free trade zones.7 As a result, co-location of parks with ports create opportunities for economic growth in Africa. BRI PPC projects enable participating African nations access to global supply chains, increasing exposure of local products and maritime services to additional international trade markets.8 The branding for these projects has a captive audience. Chinese entities are actively financing, constructing, or operating 46 sub-Saharan African ports, and 10 of these infrastructure projects span the coasts of West Africa.9 China is further leveraging the PPC to gain strategic access in Western Africa through deep water port projects. A 2014 article in The Namibian referred to Chinese news commentary that suggested plans for a strategic naval base in Western Africa in Lagos Port, Nigeria.10 Although Beijing has not confirmed the Lekki Deep Sea Port project will support military operations, most Chinese-backed infrastructure development is designed to be dual-use civilian-military ports.11 This is known as China’s “First Civilian, Later Military” approach to laying the groundwork for future military endeavors without raising attention.12 Deception is a hallmark of strategy, as in a game of chess, or the more apropos game of “Go.”

Why West Africa, and Why Now?

Unveiling the significance of China’s BRI activities in West Africa and the necessity of a focused and resourced plan to address China’s expansion requires a framework for understanding Chinese strategic thought. During a 2016 National Press Club discussion on U.S.-China strategy, Willliam “Trey” Braun, a retired Army colonel and research professor at the U.S. Army War College’s Strategic Institute, used the game of “Go” to illustrate Chinese strategy.13 Go is a two- player game that uses a 7"x7" or 9"x9" board with intersecting lines that form equal grids, and sets of white and black “stones” (one color per player) for placement on grid intersections. Once placed, these pieces do not move. The goal is to “capture” and remove an opponent’s stones by blocking empty intersections of an opponent’s stone with two or more stones. The strategies of Go include keeping stones connected to each other to resist capture; avoid scattering stones across the board and making weak groups; strengthening weak groups by attaching more stones; surround empty spaces with “forts” – strong positions – to increase safe play spaces; and saving safe spaces for later use.14 Figure 1 15 depicts the concept of “forts” on a Go board. Braun explains that game play unfolds without apparent attacks, and the aim is to win without fighting. While Go produces a winner, a loser who played well is able to walk away knowing that it was not a complete loss since “wins” in various sections of the board remain.16 In this vein, competition is enduring, and influence can be maintained and leveraged later; a dynamic analogous to business, where market share fluctuates over time.

Figure 1. Depiction of “forts” on a Go board.

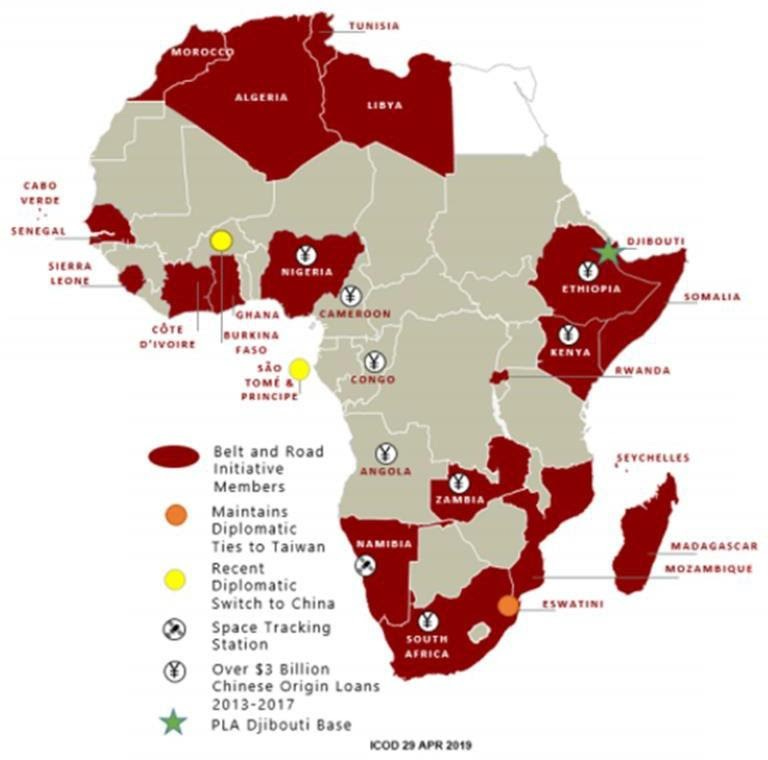

Figure 2 17 depicts China’s activities and BRI investments in Africa. Viewing the continent from a game of Go perspective, China’s strategy reveals itself by the locations of BRI investments – placement of stones – across the continent. Tellingly, in discussing overseas military expansion, Chinese officials refer to “strategic strong points” instead of “overseas basing.”18 This phenomenon is already well underway on the east coast of Africa in Djibouti, and an example of Beijing’s “First Civilian, Later Military” development approach.

Figure 2. China’s BRI members, investments, and influence in Africa.

The strategy of Go infers that China’s next moves across the continent will likely take place in West Africa. This region is rich in natural resources such as gold, diamonds, timber, and oil. Non-BRI member nations and comparatively under-represented markets are gaps in China’s execution. In 2019, USAFRICOM identified six official BRI member nations in West Africa: Cape Verde, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Nigeria.19 BRI investments in the region include the building of major dams in Guinea and Cote d’Ivoire (the latter recently garnering $7.5 billion in infrastructure investments) and the Dakar-Bamako rail line deal signed be tween Mali and China, which packages an $8 billion railway project connecting Mali to the Conakry port in Guinea.20 The burgeoning relationship between China and Nigeria is a portent of what could unfold in West Africa, absent a focused and resourced approach to competition with China’s BRI in the region.

Nigeria Case Study: A forecast for West Africa if BRI remains unchecked.

Through bilateral relations, China continues to aid the development of Nigeria’s infrastructure, and is a boon for the recipient nation. Nigeria is now the primary trade partner and the largest export market for China in Africa, surpassing Angola and South Africa.21 Nigeria makes an attractive partner for several reasons. The nation has a large population, an emerging economy, and a plethora of untapped natural resources. Nearing the capacity to produce three million barrels of exportable oil per day,22 Nigeria has the ability to negotiate equitable trade agreements. China has a high need for imported oil due to growing populations and shrinking oil reserves.

Recognizing this need and tapping into long-standing relations, Nigeria continues to build on a foundation of Chinese investments and mutual benefit. However, China’s investments in Nigeria are also self-serving. Enhancing Nigeria’s oil production capabilities and railway transportation capacity builds opportunities for economic growth, but more importantly for Beijing, facilitates transporting Nigerian oil to China. Nigerians seek to retain China as an economic partner because Beijing’s demand signal is steady, predictable, and indicative of export potential for the foreseeable future. To meet the export demands for oil, infrastructure investments in Nigerian ports make for a lucrative proposition.

China’s investment practices in Nigerian ports indicate two agendas: support for export ing petroleum products and strategic dual-use commercial and military deep-water access. As China becomes more dependent on petroleum imports, they seek to purchase petroleum mining rights and refining products for international export. With plans to increase production at three additional offshore drilling locations, the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) remains the largest offshore oil and natural gas developer and extractor in Nigeria.23 To further capitalize on these investments, China Petrochemical Corp (Sinopec) signed an agreement to purchase its first refinery on the African continent, bringing Beijing’s ambitions to extract, refine, and export petroleum products from this region closer to reality.24 These strategic investments in Nigeria and with other African nations promote China’s influence in the region.

Today, China continues to invest heavily in Nigeria’s port expansion. The Lekki Sea Port is a prime example. China’s initial $221 million funding for this $1.6 billion deep sea port will increase by an additional $629 million for the first phase, which includes a power plant and several shore-side development projects.25 The magnitude of these investments provides inherent leverage to the investors. When China Harbour Engineering Co. finishes construction, Beijing will hold majority ownership in the Lekki Sea Port, which is expected to become the deepest port in Sub-Saharan Africa.26 BRI investments have taken root over land in Nigeria as well. Breaking ground in February 2021, China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation’s $2 billion rail line project connecting Nigeria to Maradi, Niger will bolster transportation of commodities from within Africa for export.27 Beijing’s investments in projects that boost capacity for the extraction of Nigeria’s natural resources are clearly intended to increase Chinese economic prosperity. This economic boost, in tandem with strengthened bilateral relations, provides Beijing with options for future military expansion.

Port development and infrastructure investments in Nigeria support Beijing’s secondary agenda in the coastal nation: dual-use commercial and military access. China’s political and military affairs continue to make inroads with the Nigerian government, and the Nigerian military view China as a strategic partner in security and maritime stewardship. Over the last decade, at least two new Nigerian offshore patrol vessels were built by Chinese companies,28 and the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has participated in several military-to-military engagements with Nigeria. In 2018, the PLAN’s Yancheng frigate participated in the Nigerian-led mari time conference, along with other West African nations, in an international maritime conference and regional naval exercise hosted by the Nigerian Navy.29 Beijing’s focus on security cooperation and military engagements will likely increase as China invests more in the region. Beijing’s agenda is to ensure the security of Chinese investments in strategic seaports, offshore petroleum exploration, and extraction of natural resources. In the context of Chinese strategy, this blended application of economic and military instruments create “forts” on a Go board, representing strategic moves aimed at deterring influence by competing nations, preserving China’s political position, and ensuring that the BRI remains the preferred partnership mechanism in Nigeria.

China’s soft-power activities in Nigeria serve as a forecast of what could continue to play out across West Africa if the BRI remains unchecked. USAFRICOM’s current efforts in the region appear to focus primarily on building partnerships through military engagements, and there are no clear indications that a focused and resourced approach to GPC with China’s BRI is in place.

What are USAFRICOM’s current operations, activities, and investments in the region?

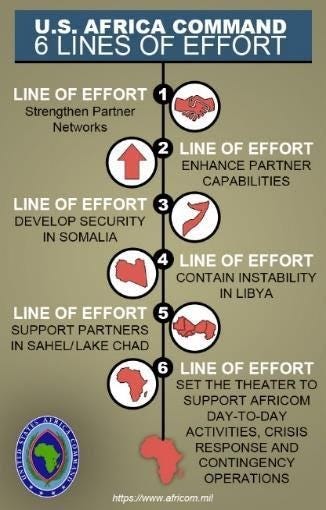

Since its inception as a command in 2007, USAFRICOM has applied a partner-centric, interagency approach to achieving U.S. foreign policy goals.30 The command capitalizes on military support to diplomacy and development by conducting security activities that complement Department of State (DoS) and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) efforts that enable economic advancement,31 and more direct competition with China’s BRI activities through soft power. Figure 3 32 depicts USAFRICOM’s lines of effort (LOEs). In West Africa, the following LOEs are the most closely-aligned mechanisms that set conditions for GPC with China’s BRI:

LOE 1 – “Strengthen Partner Networks,”

LOE 2 – “Enhance Partner Capabilities,”

LOE 5 – “Support Partners in Sahel/Lake Chad,” and

LOE 6 – “Set the Theater to Support AFRICOM Day-to-Day Activities, Crisis Response, and Contingency Operations.”

Figure 3. USAFRICOM LOEs

Episodic interactions and forward basing of resources underpin USAFRICOM’s operations, activities, and investments (OAIs) that support LOEs 1, 2, 5, and 6 in West Africa. These periodic engagements and exercises entail heavy application of diplomatic, information, and economic levers interwoven with military-focused events. Investments in infrastructure for forward-basing of resources primarily focus on increasing USAFRICOM’s capacity to counter violent extremist organization (VEO) activities through military means.

USAFRICOM OAIs include three programs supporting LOEs 1 and 2 through periodic engagements in West Africa: Africa Partnership Station (APS), African Maritime Law Enforcement Program (AMLEP), and the State Partnership Program (SPP).33 These programs demonstrate the strong commitment of U.S. support to the region. During an APS engagement in 2019, the USNS CARSON CITY deployed a training team to several West African nations, focusing on small boat repair, maritime security, first responders, and clinical care.34 The AMLEP is a robust five-phase program that aims to enable partner nations to independently conduct maritime law enforcement operations and counter threats along their coasts.35 The National Guard’s SPP is also an enduring program, described as “a key U.S. security cooperation tool that facilitates co-operation across all aspects of international civil-military affairs and encourages people-to-people ties at the state level.”36 Together, these activities directly strengthen relationships, increase capacity, and build capabilities of partner nations to lead crisis response and stabilization efforts in the region. Access, basing, and overflight often result from these heightened relationships.

In 2014, the Niger government approved the development of a forward operating base (FOB) and subsequent overflight access to support U.S. forward basing in Agadez.37 This FOB became the second largest U.S. footprint in Africa by 2016 and U.S. UAVs provided support for partnered counter-VEO operations since. This forward basing takes a partner-centric approach and affords USAFRICOM a mechanism to directly execute LOEs 1, 2, 5, and 6. The base serve s as an aerial port of debarkation, capable of supporting force flow for a host of crisis scenarios be yond personnel recovery. By blending foundational soft power efforts with a partner-supporting military one, USAFRICOM can achieve all of its LOEs in West Africa.

China’s BRI and USAFRICOM LOEs share the same end states and similar ways or mechanisms to achieve these goals. However, the means to conduct OAIs contrast in application and priority. China’s approach is to limit the operational reach of its military to maintain a strong presence close to its homeland, relying on soft powers through the BRI in Africa to set conditions for future military expansion. Conversely, the U.S. applies the strength of U.S. military power projection by way of USAFRICOM first, to augment and support the application of U.S. soft power instruments of national power. To maintain its competitive viability, China leverages influence through non-military partners such as The Commission on the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). While USAFRICOM’s OAIs broadly serve to set conditions for the application of soft power, to engage in GPC below the level of armed conflict, opportunities exist to implement refinements based on a BRI-focused approach.

What would a more effective approach to competition with BRI in West Africa require?

GPC in West Africa requires a BRI-focused approach, and requisite resources to execute the approach. USAFRICOM’s OAIs associated with LOEs 1, 2, 5, and 6 aim to set conditions for security and stability in West Africa by increasing and enhancing counter-VEO capabilities. Accomplishing the intermediate objectives of these LOEs directly support interagency actions to effectively compete below the level of armed conflict through diplomatic and economic means.

Good governance and security are key requirements for economic development through U.S. investments and trade agreements. However, according to a DoD Inspector General report, violence stemming from VEO activities accelerated during 2018-2019, requiring USAFRICOM to shift from a “degrade” strategy to a “containment” strategy, and suspending USAID humanitarian programs due to the deteriorating security conditions in the region.38 Maintaining or increasing the current force posture in Africa is vital to enabling U.S. interagency mechanisms to work, and accelerating Africa’s self-sustaining prosperity. While USAFRICOM’s campaign plan lays out counter-VEO objectives, great power competition with China’s BRI activities in West Africa is not specifically addressed. An updated assessment of ways and means needed for USAFRICOM to expand the competitive space and outpace China39 is required. The 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS) provides a blueprint for what is needed: Adopting a paradigm shift in burden-sharing for security and stability in West Africa, and enhanced application of the information instrument of national power, while engaging in competition activities, are potential ways to update USAFRICOM’s approach in order to “compete to win”40 more effectively against China’s game of Go in West Africa. Adversary stones of the game – BRI investments – are already in place, and given Beijing’s strategy, a growing military presence on the continent is all but certain.

As the Joint Force continues to align with the NDS for GPC, force posture adjustments to rebuild readiness may lead to further decreases in capacity for security cooperation and assistance efforts in West Africa. Countering VEOs remain a priority, and options for managing risks from further posture reductions will require tough decision-making across the DoD and USAFRICOM. The NDS offers a potential way to mitigate these risks by supporting relationships to address “significant threats” in this AOR:

We will bolster existing bilateral and multilateral partnerships and develop new relation ships to address significant terrorist threats that threaten U.S. interests and contribute to challenges in Europe and the Middle East. We will focus on working by, with, and through local partners and the European Union to degrade terrorists; build the capability required to counter violent extremism, human trafficking, trans-national criminal activity, and illegal arms trade with limited outside assistance; and limit the malign influence of non-African powers. 41

In the 2020 USAFRICOM Posture Statement, General Townsend relayed an African leader’s concerns to illustrate the risks in gapping U.S. assistance: “a drowning man will accept any hand.”42 Since West African needs outpace infrastructure investments, acceptance of assistance from Beijing will continue. However, opportunities for the U.S. to advance its interests through aid and investments remain, despite China’s presence. A win-win situation may result for West Africans, who can reap the benefits of competition. From a business model perspective, this dynamic yields better products at competitive rates over time. In some cases a third party may win a bid, presenting wins to Africa as well as the U.S., as this stymies China’s influence as a result.43 Indeed, not all BRI investments are detrimental; some may even be essential44 especially when U.S. policy limits access to loans and grants.

In the realm of security cooperation – during competition below the level of armed conflict – there is potential for a business model approach as well. Another facet to the game of Go that Braun illuminates is the idea of engaging in dialog with China, including military-to-military engagements45 that could lead to mutually beneficial multilateral cooperation in the region. A point of departure on this endeavor could be where U.S. and China’s interests converge: peacekeeping operations. Both countries recognize that security and stability are inherently linked to development. Conditions for these kinds of engagements have a precedence founded in academia. In October 2016, the DoS sponsored a two-day exchange in Washington, D.C. for a delegation of peacekeeping and stability experts from the People’s Republic of China, hosted by the U.S. Army War College’s Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute (PKSOI).46 Accepting the reality of China’s presence and activities should give pause to reconsideration of USAFRICOM’s LOE 1 – “Strengthen Partner Networks,” and reassess what it means to “counter the activities of external actors such as China,”47 whether being the “preferred security partner in Africa”48 is truly binary, and if there is room to share the security burden through the formation of a carefully defined new relationship with China. As previously recognized, Africans welcome Beijing’s assistance, making China a de facto local partner, at least with a growing number of African nations. Should U.S. policy adjust to these realities, USAFRICOM and its interagency partners should continue to leverage a whole-of-government approach, applying the information instrument across all levers to synergizing efforts for greater effects.

The informational instrument of national power is vital to strategy. Effective use of this lever entails creating, exploiting, and disrupting knowledge49 to gain advantage over an adversary through the power of influence. In his testimony to the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Dr. Ely Ratner, Maurice R. Greenberg Senior Fellow for China Studies, Council on Foreign Relations, made several recommendations for U.S. policy. He presented the need to “[r]ebuild institutions for U.S. information operations,” citing that China’s influence gained through BRI, and the ancillary effects on important U.S. security and military matters far outweigh the economic value of the projects.50 While the U.S. continues to rebuild its post- COVID19 economy, low-cost, high benefit solutions remain paramount. Engagements by USAFRICOM civil affairs teams to advise and assist West Africans with transportation infrastructure improvements, and partnership building activities of the SPP are viable options.51 Unlike the Army’s nascent Security Force Assistance Brigade (SFAB), which provides full time security cooperation capacity during unit rotations, SPP employs teams at all echelons (up to and including key leader engagements at the senior general officer/flag officer level) to engage with partner nations, and do not require a logistics footprint to support the program’s episodic engagements. Previous research assessing the cost-benefit, effectiveness and perseverance of the SPP supports the viability of expanding the program in West Africa.52 While civil affairs teams and SPP activities provide long-term sustainable solutions, U.S. branding efforts at every touch point with West African partners require coordination and synchronization to achieve unity of effort and resultant synergy.

When the full measure of U.S. application of the informational instrument of national power is brought to bear, what was once opaque becomes clear. Where there is clarity, the solu tions for Africa’s unfolding opportunities for prosperity become evident, and USAFRICOM’s ability to consolidate gains in its on-going effort to compete and win in great power competition with China increases. The next moves need to be made in West Africa, where the intersecting lines of competitive space for U.S. influence remain open.

The Way Ahead... African Solutions for African Opportunities.

As an economy of force geographic combatant command, applying sound business sense during planning for competition below the level of armed conflict in West Africa can be beneficial at USAFRICOM. All levers of national power are incorporated, and the application of force – the military lever – is used judiciously, and in this context, plays the role of security elements that oppose malign forces that intend to cause harm to U.S. and partner establishments. The economic lever represents bankers, and the diplomatic lever represents clientele services. Each touch point between the U.S. and host nation partners is an opportunity to expand the marketing reach of the U.S. brand, and its core values of democracy. The information lever is the marketing campaign, which if executed properly, gains influence and market share. Combined, a focused information campaign and high-quality relations between U.S. and African partners will create opportunities for repeat business, and through transparency, increase repute as Africa’s partner of choice. Fostering these relations require adept application of all available resources in concert to achieve the best results for all parties. Warfighters, regardless of service, should recognize that force application and heavy reliance on the military instrument as the lead effort is not always effective; neither feasible, acceptable, nor suitable given the operational environment. In the game of Go construct, Chinese strategists have been developing and applying these tenets for millennia.53 Development of joint planners must continue to emphasize methods for leveraging all instruments of national power in order to enhance the Joint Force’s ability to compete in com plex operational environments such as GPC with China and the BRI.

Caveat emptor – let the buyer beware – remains the standard caution to the nations of West Africa, where the opposing marketing campaign for BRI investments continues to loom. USAFRICOM, in coordination with interagency partners, should craft a focused approach to competition with China’s BRI, and this approach should be resourced at the very least, by reprioritizing efforts in this region. At the time of this writing, the Biden Administration has not yet promulgated its recalibrated strategy for West Africa. However, it remains likely that the U.S. will continue to carry forward its principles under-girding African solutions for the problems inherent in the opportunities that lie ahead in West Africa. USAFRICOM, in close coordination with ECOWAS partners and allied nations, should continue to leverage corporate talents, and potentially welcome new partners to the table. Collaborative competition can be good for the prosperity of Africa, and will serve to prevent miscalculation with China in the region. The time to make the next move is now.

About the Authors:

Lieutenant Colonel Wandasan is assigned as the J359 Global Force Management and Readiness Branch Chief at the National Guard Bureau.

Commander Andrew Davis is assigned to the JSOC Intelligence Brigade at Fort Bragg North Carolina.

Lieutenant Commander Bryan Kilcoin is assigned to Maritime Security / Law Enforcement section at Coast Guard Atlantic Area.

Major Branndon Teffeteller is assigned to the Operational Contract Support Integration Cell at United States Central Command.