Understanding French Defense Cooperation in Africa

By Lieutenant Colonel Andrus W. Chaney, U.S. Army

The purpose of this article is to provide Security Cooperation Offices, planners, and action officers with an understanding of French Defense Cooperation with the goal of assisting them in working more with French counterparts and to enhance U.S. and French Security Cooperation efforts in Africa. Security Cooperation efforts consistently receive increasing scrutiny at all levels of government, therefore we should look more to our allies to synchronize effects.

In 2008 France released its first defense white paper since 1994. In it, France outlined the purpose of its security-defense cooperation mission: to develop the capacity of its partner nations to respond to crises and to support peacekeeping operations led by regional or sub-regional organizations. It further defined its goal for security cooperation mission in Africa in its 2013 white paper: “Support for the establishment of a collective security architecture in Africa is a priority of France’s cooperation and development policy.” In 2014, the chief of the Direction de la Cooperation de Securite et de Defense (Directorate of Cooperation of Security and Defense - DSCD) further described the change in France’s approach to defense-security cooperation as “Structural defense cooperation in France has traditionally taken a bilateral approach: advice to the country's senior civil and military authorities, training of senior staff, and specific technical training, for example in the area of scientific and technical police. In recent years, it has been associated with a multilateral approach, particularly through the regional schools with a regional vocation, which drain students from several African countries, even from the whole continent.”

Collaboration between the U.S. and France's operational efforts are increasing in Africa through an exchange of liaison officers, staff talks, and participation in regular multilateral planning groups. However, security cooperation/defense cooperation efforts are minimally integrated at the embassy level, among Security Cooperation Officers (SCO), or at the Joint Staff and Combatant Command General Officer and Liaison Officer levels. A few of the J5 planners are also communicating together, but overall none of the G5 planners or action officers are working together, yet.

In Africa, the U.S. executes Security Cooperation through U.S. Africa Command (USAFRICOM) and Security Assistance through the Department of State’s African Affairs and Political/Military Bureaus. The U.S. conducts Security Cooperation and Security Assistance with 48 African partners of the 53 countries in USAFRICOM's area of responsibility, and has Defense Attachés who cover all 53 countries. The Joint Staff, through the National Guard Bureau, has 14 State Partnership Program agreements with African partners. Security Cooperation and Security Assistance are conducted through the Security Cooperation Officers (SCO), with oversight by their Senior Defense Officials/Defense Attachés (SDO/DATT). The U.S. does not have formal bilateral defense or security cooperation agreements with any African countries, in comparison to the accords France has with its many African partners. However, USAFRICOM does have several information sharing, status of forces, and acquisition and cross-sharing agreements with partner nations in Africa. It has signed other Memoranda of Agreement, but they are more general in scope and commitment when compared with similar initiatives completed in theater by the French.

The U.S. has contributed hundreds of millions of dollars in Foreign Military Financing (FMF), several more million dollars towards International Military Education and Training (IMET), and even more hundreds of million towards Peacekeeping Operations (PKO) in Africa over the past decade. The U.S. maintains one permanent military base in Djibouti and several contingency locations in other parts of Africa. The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) has no long-term embedded military advisors in Africa; but the Department of State (DoS) has a few civilian contractors integrated at the executive level to advise senior leaders in a small number of countries. The U.S. has 56 military observers in United Nations missions in Africa but does not contribute any troops to UN missions there. Nonetheless, U.S. is the most significant security cooperation provider in Africa when comparing total monetary contributions.

In comparison, France has 11 Defense Agreements, 17 Cooperation Agreements and 31 Defense Attachés in Africa. These agreements cover short-, mid-, and long-term timelines and are executed by 65 military cooperants and 27 police experts. Some of these cooperants are embedded in the partner nation’s military academies, others in the 15 regionally oriented schools or the five peacekeeping training centers in Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mali, and Benin. France has four permanent bases in Africa (Senegal, Cote d’Ivoire, Gabon, and Djibouti) and contingency locations throughout the 26 Francophone countries in Africa. France has 815 military members in United Nations missions, most of which are not in Africa, but in Lebanon. France executes security and defense cooperation through its Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), and military assistance through its Joint Staff Headquarters in Paris, France.

In reviewing the U.S. and French contributions to African militaries it becomes clear that France and the U.S. are the most significant external military partners to Africa. The main differences between the two are: 1) France invests more with its personnel and less with equipment; 2) the U.S., through USAFRICOM, covers the entire continent whereas France focuses mainly on West, Central, and Africa Indian Ocean Islands, or areas aligned with its colonial past; and lastly, 3) France contributes more to United Nation (UN) missions in Africa; this is logical considering that three of the current 15 UN mission are in former French colonies.

Structural and Operational

France's security-defense cooperation efforts fall into two broad categories: structural and operational. The structural category has a long-term planning horizon of five to ten years and includes activities such as building a military academy or a de-mining unit (building partnership capacity). The DCSD, under the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs (MFEA), executes these programs through the Defense Attaché assigned to the partner nation and by embedded trainers and advisors, most of whom are categorized as "cooperants." The operational category falls under their Ministry of Defense and includes activities such as peacekeeping pre-deployment training and short-term police and border security training events. It also includes military assistance activities such as Operation Barkhane, the G5 Sahel initiative, and any advise/assist/accompany missions with partner nations.

The Directorate of Cooperation of Security and Defense (DCSD)

The DCSD is an essential component of French diplomatic and development efforts in Africa. It is of one of the sub-organizations in the Directorate-General for Political Affairs of the Ministry of European and Foreign Affairs (MEFA), within their Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which is similar to the U.S. Department of State. The DCSD is responsible for structural cooperation with foreign states in military, police and civil protection areas. It implements, at the request of partner countries, targeted actions of training, advising, and material assistance (equipment and construction). This whole-of-government approach offers accomplishable solutions, combining in particular the implementation of adapted training courses and the deployment of the necessary equipment; the creation of professional military education schools and the development of professional training; and targeted projects and the insertion of advisors at the appropriate level. Organizing the DCSD under the MFA reflects the lead role the MFA plays in the bilateral and multilateral relations in the security/defense and security/development areas.

DCSD’s concept of security/defense cooperation includes areas such as military, police, and civil protection (firefighters, prison, border patrol, civil work programs, etc.). Security focuses on securing the country internally (Ministry of Interior), and Defense focuses on defending (Ministry of Defense) against external forces. DCSD comprises diplomats, military, police and civil protection experts. It consists of more than 300 personnel in 140 countries, with its primary focus on Africa. Along with the security/defense cooperation paradigm, DCSD splits its forces in each partner nation through two different Attachés: the Defense Attaché and the Interior Attaché. These are comparable to the U.S. Defense Attaché, who executes Security Cooperation for the DoD and Security Assistance for the DoS; and somewhat similar to the U.S. Embassy Regional Security Officer (RSO) who implements security assistance for the DoS for police and border forces.

The French deploy their security and defense cooperation differently based upon each region or area of the world. In sub-Saharan Africa, their projects are focused on the partner nation, preferring to include a regional or sub-regional approach, and executed through professional military education (PME) schools and peacekeeping training centers. These centers focus on UN peacekeeping training, specific military capabilities (Infantry, Engineer, Medical), or Gendarmerie (Police) academies. Initially open to mainly Francophone countries, they have now expanded to Anglophone and Lusophone countries. The French projects in North Africa and the Middle East, on the other hand, are focused primarily on stabilizing internal security issues.

Cooperants (Embedded Advisors)

Cooperants are increasingly representative of DCSD’s portfolio. These advisors come at the request of the partner nation and are usually a single embed for a defined amount of time, or multiple embeds over a period of time. These advisors can be military, gendarmerie, or police assigned to the force generation or executive management level (the Prime Ministry, the Ministry of Defense, the General Staff, the Ministry of Interior, etc.). These technical experts evaluate all or part of the security and defense realms and analyze the fundamental issues the partner nation is experiencing. Then they are challenged with providing solutions that are adapted to the partner nation. These advisors live in the country for two or three years, with their families, and wear the uniform of the partner nation. The only comparable element in the U.S. approach in Africa is the DSCA Ministry of Defense Advisor (MoDA) program, of which there is one advisor in Botswana.

Cooperation with International Organizations

The DCSD also conducts military cooperation activities with international organizations that are regional in scope. Permanent advisers are assigned to African regional or sub-regional organizations such as the African Union (AU), Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), and African Standby Forces such as the East Africa Standby Force (EASFCOM). These advisors are mainly assigned to the Executive Secretaries or their deputies in charge of political, defense and security affairs.

France has pre-deployed forces in several African Regional Economic Community states, including Senegal, Cote d’Ivoire, Gabon, and Djibouti. Each is commanded by a brigadier general who is responsible for the pre-positioned forces in the host nation as well as regional coordination with African Standby forces (ASF) in their region. In close cooperation with the Defense Attachés, each of their staffs prepares a yearly plan of cooperation that is approved by the Joint Staff in Paris. The DCSD also developed multinational cooperation projects in the region, including the Peacekeeping School in Bamako, Mali and the Ouidah Humanitarian De-mining Center in Benin. Multinational cooperation partners for these peacekeeping centers include Argentina, Belgium, Benin, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Japan, Mali, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and the U.S.

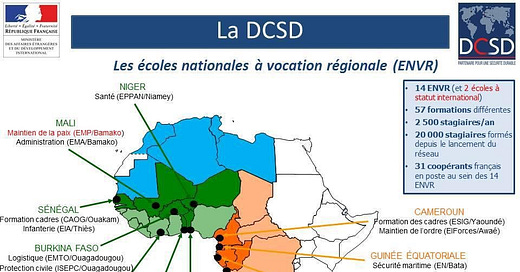

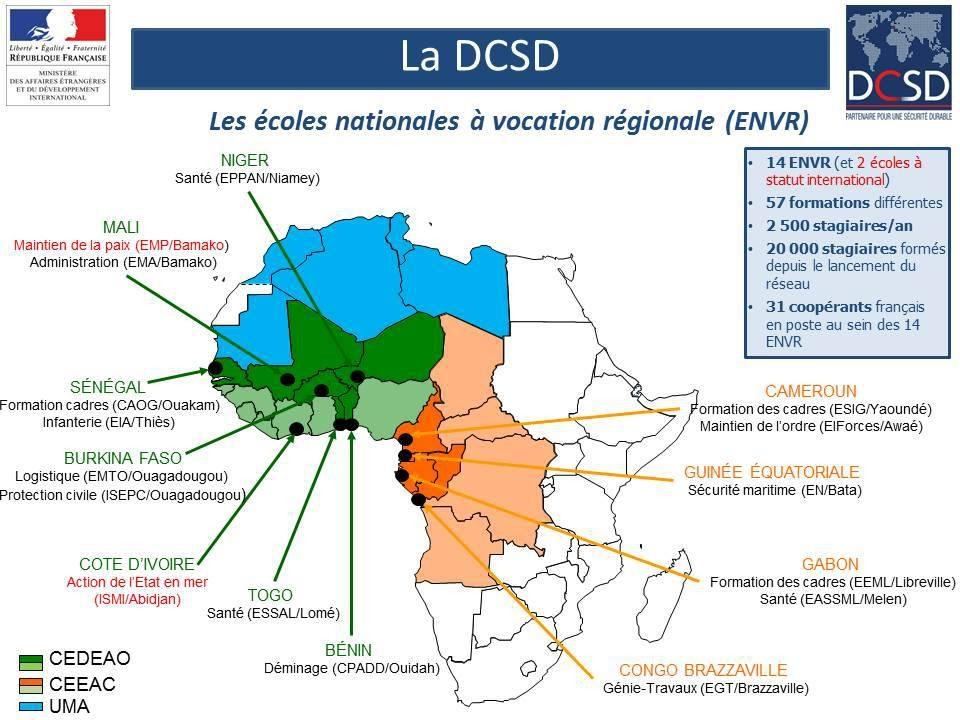

Ecoles Nationales a Vocaction Regionale (ENVR) (National Regional Vocational Schools)

The ENVR concept is designed to help a country develop a specialized military school that is open to attendees from its military as well as from other countries in the region. The host country provides real estate, buildings, resources, and supervision necessary for running the school. France also provides technical support and expertise in training curricula. The host country agrees that the school welcomes students from other African countries, whose transportation and training fees are paid for or sustained by France.

On average, ENVRs train 2,500 personnel each year in areas as varied as peacekeeping operations, internal security, health, de-mining, administration, offshore action or more recently, civil protection. They have become an essential element of French cooperation policy in Africa. Since 1997, more than 20,000 personnel have been trained in these schools supported by France.

Location of ENVR in sub-Saharan Africa

Language Training

The DCSD develops cooperation for French and non-French-speaking countries through access to various training programs in France and abroad. The Directorate coordinates French language learning programs, with the goal of providing access to national schools, regional schools or French military and security schools, and to allow better integration in peacekeeping operations. Each year, DCSD sends teachers from the National Center for Academic and Educational Works and the General Association of Retired Practitioners to instruct French as a second language.

The learning objective is for the student to reach a level of language skills to permit attendance at an ENVR, or at French military and security schools. This training allows for the integration into UN peacekeeping operations, of which three of eight missions in Africa are in French-speaking countries. More than 35,000 military and police officers around the world benefit from a training program funded by the DCSD. France regularly highlights the need of French language training for peacekeepers in UN peacekeeping missions.

Operational Cooperation

An important priority is synchronization between structural and operational efforts. The principle of setting up operational cooperation centers, which can replace or adjust the troop composition during the phases of crisis resolution, and is linked with French structural cooperation arrangements, is particularly interesting. There are operational cooperation centers in Cote d’Ivoire, Afghanistan, and Central African Republic.

Reinforcement of African Peacekeeping Capabilities (RECAMP)

Through RECAMP France supports African nations' initiatives to assume ownership of crisis prevention, participate in UN Peacekeeping missions, and to strengthen local defense capabilities. This strategic approach is based on three lines of effort: 1) education and training, 2) logistics and 3) operational support. Furthermore, to conduct the RECAMP program, France set up several depots as supply reserves, where pre-deployed equipment is warehoused until required by their African partners. Use of depots has two objectives: storage of equipment to be delivered at a later date, and facilitation of RECAMP operational training conducted by its pre-deployed forces.

Military Operational Assistance

The French Army executes Security Force Assistance through a four-stage approach. This approach is conducted by the regionally assigned forces in the four pre-positioned bases in Africa as well as through units from the French mainland.

- Basic Courses: Conducted by Technical Instruction Detachments (DIT- Détachements d'instruction technique). These are three-day to three-week courses similar to U.S. military-to-military events (M2M), Enhanced International Military Education and Training (E-IMET), or Security Force Assistance courses provided by contractors.

- Long-Term Courses: Conducted by Operational Instruction Detachments (DIO - Détachement d'Instruction Opérationnelle). These are longer term courses covering multiple branches of service. They are not permanent and are similar to U.S. Security Force Assistance/Building Partner Capacity (SFA/BPC) train-and-equip programs.

- Collective Training: Conducted by Operational Military Assistance Detachments (DAMO -- Détachement Opérationnel d'Aide Militaire). These are platoon or company level training courses conducted primarily through the RECAMP program, and also similar to U.S. SFA/BPC train and equip programs. However, these tend to be longer (over a year) than U.S. equivalents, and include a permanent staff that is augmented with temporary duty personnel for three to four months.

- Operations/Combat: Much like U.S. Special Forces the French Forces also provide advisors who advise, assist, and accompany foreign forces in selected operational missions.

Cooperation Agreements

The French Cooperation Agreement is somewhat new (emerging over the past ten years) and comprises a technical and legal instrument intended to develop and formalize the connection between France and a partner nation. It is similar to the U.S. Millennium Challenge Corporation but narrower in focus and tailored to Security Cooperation. In this author's opinion, it is the fundamental agreement that the U.S. should mirror for Security Cooperation/Security Assistance in Africa.

The Agreement is systematically structured into four components: 1) mutual interests of the two parties; 2) roles of the DCSD and the partner; 3) the general principles of the partnership; 4) the framework of the agreement and motivations each country has for the agreement. It also specifies the contributions of signing parties: 1) clarifies legal aspects for each partner and establishes the duration of the agreement (a minimum of three years); and 2) outlines a way to highlight, discuss and resolve disputes.

From the France government perspective, the Cooperation Agreement has the following objectives: 1) achieve the goals identified by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA); 2) formalize the pre-existing connections regarding information and intelligence sharing; military sales opportunities that may benefit the partner and opportunities for cooperation that benefit DCSD; and increase France’s influence in the countries concerned and international organizations (UN, European Union); and 3) complete actions agreed to for specific programs/project briefs.

These programs are the second component of the agreement. They explain on a case-by-case basis specific partnership actions: organization of a seminar day, action in one of the training centers initiated by the DCSD, joint drafting of a monthly information newsletter, and joint participation in a priority program. These briefs are signed by the MFA and the host nation.

The third component of the agreement is an ethics charter found in the annex and indicates all the main fundamental principles that should be observed, such as respecting human rights, the outreach of France’s expertise and their concern for always acting lawfully.

Funding

In 2013 France allocated $130.8 million to defense, internal security, and civil protection programs in Africa. In comparison, the U.S. DoS and DoD spent over $700 million on these missions. However, France committed over 100 permanent personnel (the same person over more than one year) to train and advise forces in West and Central Africa, whereas the U.S. employed no permanent personnel to train and advise forces in Africa.

Conclusion

The French do three things better in Africa than the U.S. in the Security Cooperation mission. First, they commit more human capital than fiscal capital because they understand that change in Africa requires relationships and time. Second, they engage in long-term agreements in Africa and commit to building defense institutions. Third, they choose the most capable candidate, not the most connected one.

The U.S. does one thing better than the French in Africa for Security Cooperation -- incorporate the experiences and lessons learned in multiple recent conflicts. Africans see Americans as the premier fighters in the world. The U.S. representatives do not talk down to their African counterparts, but, instead, view them as a partner military because the U.S. has no colonial perspective to hinder the relationships.

The time has never been better for improving Franco-American cooperation in Africa. France’s military is now consumed by Mali – it is their equivalent to our Afghanistan, yet they are still expanding into Anglophone and Lusophone countries in Africa. The challenge of synchronizing French and U.S. Security Cooperation efforts lies in how the French MFA and the U.S. DoS and DoD funding cycles are mismatched. Achieving full synchronization with the French MFA, DCSD, French Defense Attaches; and U.S. DoS, DoD, and USAFRICOM is impossible. Simply put, there are too many people and too many policy wonks who will overcomplicate the situations.

Achieving Security Cooperation synchronization in Africa must be guided by a solely military affairs strategy that can streamline, plan accordingly, and set achievable effects. If our two nations' military planners could achieve unity of effort in our long-term theater campaign plans, then we could present a more synchronized justification and plan to policymakers and funding authorities. We can do this best by first understanding each other's systems for Security Cooperation/Defense Cooperation.

About the Author

Lieutenant Colonel Andrus W. Chaney is a FAO specializing in sub-Saharan Africa and is the SDO/DATT to Cote d’Ivoire. Previously he was the Office of Security Cooperation Chief at the U.S. Embassy Djibouti, the South/East Africa Branch Chief in the Security Cooperation Directorate, U.S. Army Africa, and temporarily served as U.S. Army Africa Liaison Officer to the French Joint Staff.