Disclaimers:

The views expressed herein are the author's own and do not necessarily represent those of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

This article references the Defense Institute of Security Cooperation Studies (DISCS), however, as of this printing DISCS is now the Defense Security Cooperation University.

A significant part of the mission of The Defense Institute of Security Cooperation Studies (DISCS) is to conduct educational courses and provide research and other support designed to improve the knowledge and enhance the skills of a wide audience in the field of security cooperation. DISCS students include U.S. military personnel, Department of Defense (DoD) civilians, other U.S. Government agency employees, representatives of the U.S. defense industry, and military and civilian counterparts from foreign governments, Because of DISCS involvement with both civilian and military groups and institutions, as well as the very nature of 21st century security cooperation which extends beyond simple mil-to-mil contact, our instructors and students should have situational awareness of the components of civil-military relations.

Understanding the definition of civil-military relations promotes understanding between groups active in the field of security cooperation, and may help in decreasing conflict related to civil-military relations. In this article, I argue that civil-military relations are more than just a naturally occurring by-product of civilian and military interaction. Rather, understanding what comprises civil-military relations in a democracy – even a fledgling one -- involves a deeper appreciation of the role society plays in the civil-military nexus. In addition, I propose that embracing society’s role in civil-military relations can decrease conflicts in civil-military relations.

The Principal-Agent Theory

General Martin Dempsey, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and principal military adviser to President Obama, noted that “civil-military relations are a rocky road. . . . The question is how it [the relationship] is managed and understood.” No one really understands the relationship, nor the reasons for conflict between these groups, yet practitioners of civil-military relations need to understand what comprises civil-military relations to be successful in it.

Many modern civil-military theorists consider Samuel Huntington as the primary source on civil-military relations. According to Huntington, civil-military relations seek to promote the security of a nation at the “least sacrifice of other social values.” Huntington holds that civil-military relations occur between “political and military groups” and involve a “complex balancing act. Emphasizing the hierarchical nature of the relationship, at least as it exists in United States as an interaction between senior civilian government officials and subordinate military leaders, many civil-military authors have described it as “principal-agent” engagement. In the case of the United States, the political group generally has the power, with the military obeying the orders of higher authority in accordance with the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) and the U.S Constitution. Other nations have similar arrangements but may have more or less stringent hierarchies.

Western civil-military relations literature has focused on the hierarchical aspects of a subservient military serving political masters in a democracy and supports the principal-agent theory. Such theorists contend senior government officials strategize with senior military officials in the nexus comprising high-level civilian-military relations, a hierarchical, power-laden relationship revolving around discourse. The role of senior military leaders is critical: “By law and precedent, they have a right to be heard.” But are they really heard? Does the civ really hear the mil?

In civil-military contexts speaking out may be considered to border on mutiny, something to be suppressed, and is seemingly misunderstood in the military research community, suggesting incongruence with the military’s charge to give sound, practical advice. Practical military literature defines dissent through a delineation of the political boundaries between political and military groups, fodder for the principal-agent theory. That line between the groups constantly shifts and with it the definition of dissent, or speaking out, “arguing your case up to the point of decision . . . the giving of sound, accurate, fearless, objective information.” Dissent is also experientially based, a duty for the soldier to bring “professional military experience to bear in a public forum with the obligation to lead and represent the profession . . . expressly subordinate to civilian control." Indeed, dissent often begins by voice, based on experience of the dissenter who might say “based on my experience, your idea to do X in country Y will not work….”

The antithesis of conflict is groupthink and the suppression of opinions based on sound, military advice. Groups strive to maintain the illusion of consensus by avoiding open dissent and may agree too quickly. History is replete with examples where lack of dissent -- or reliance on consensus and harmony over optimal solutions -- led to disaster. The carnage of Desert One’s abortive attempt to rescue U.S. hostages held by Iran during the Carter Administration, groupthink and a feeling of invincibility in the days before the 9/11 attacks, and President George W. Bush’s consensus-seeking approach to post-war Iraq are modern instances when high-level civilian groups sought consensus -- not dissention and conflict -- in their discourse. Groups in hierarchies often display consensus-seeking approaches at the cost of poor decision-making, eliminating the benefits of dissent in organizations.

Such military theorists admit the principal-agent relationship is generally rife with conflict. Making strategy is not a peaceful process.

Conflict between Groups – Understanding Conflict in Civil-Military Relations

In conflict theory, an advantage gained over one group comes at the expense of the other, yet the theory holds that conflict ultimately preserves and strengthens the group. The struggles for collective goals are more militant than conflicts over personal issues. This is because people feel greater freedom to take extreme measures when they act as representatives of a group. Such action grants them a degree of respectability since they are perceived as altruistically working for others.

Social friction over hierarchy and power in the principal-agent theory leads to strain and conflict. Coser draws on seminal conflict theorists who argue social issues, interaction, power, authority, and hierarchies are vital, interrelated components in conflict theory. Social conflict theory components thus resonate well in civil-military contexts, where power and hierarchy play vital roles. For those that subscribe to the principal-agent theory, modern military theorists recognize the role of conflict as a naturally-occurring by-product as the military subordinates itself to government officials in the hierarchical exchange of powers the political class grants the military.

Using Coser as a base in a wide-ranging study that identified gaps in the resolution of social conflict, Wagner-Pacifici and Hall clarify and update the definition of conflict to an active construct. Noting that social conflicts run the gamut from an argument at a family dinner to wars between nations, the authors address power and hierarchies, filling gaps in conflict theory, positing that to study conflict means examining the moment when a potentially historic change occurs between groups. Oberschall notes that conflict results from purposeful interaction among two or more parties in a competitive setting, once again reinforcing social aspects: “The parties are an aggregate of individuals, such as groups, organizations, communities, and crowds, rather than single individuals.” Wagner-Pacifici and Hall suggest future studies explore dissent as an overt social conflict within geopolitical national defense arenas, that conflict is ultimately a social construct, occurring in or as a result of the hierarchies of an organization or relationship. It is the communicative social interaction between individuals or groups as they struggle for resources. Resources include discourse, power, and authority.

Thus, conflict is the struggle over values and claims to scarce resources, power, and authority, the purposeful interaction among two or more parties in a competitive setting, an ultimately social aspect.

The principal-agent hierarchy in civil-military relations drives conflict over resource competition; as in conflict theory, resources beget power. According to Wagner-Pacifici and Hall, the issue of power must be counted among the most significant regarding the resolution of social conflict.

Towards a Tripartite

However, civil-military research has progressed from Huntington’s depiction of civil-military relations comprising two groups. I contend that defining civil-military as two groups represents dated thinking and actually promotes conflict in civil-military relations, as it assumes that “two distinct bodies -- the civil and the military -- are necessary for conflict to arise.” Some modern civil-military literature advances Huntington’s theories by noting that there are actually three groups in the equation: the military, the political elite, and the “citizenry. More recently, Saas and Hall refer to the military class, the civilian class, and the presidential administration as the three groups. Saas and Hall even go so far as to offer legal definitions for the separate groups, supporting evidence that three groups comprise civil-military relations. The authors suggest, based on a formal legal finding by the Washington D.C. Circuit Court, that “military bases are military domain segregated from public life,” and that there exists a public or societal domain, a military domain, and political domains.

Thus, civil-military relations are “the relationship between civil society as a whole and the military organization(s) protecting it.” And, other researchers confirm the idea that there are three groups in the equation: the military, the political elite, and the “citizenry,” or social group.

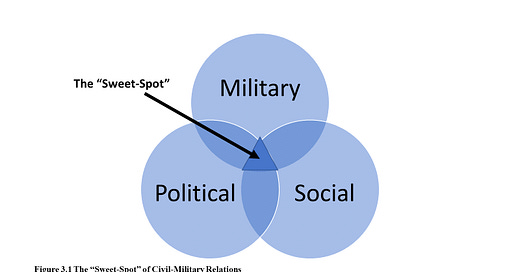

Operating in the “Sweet-Spot” of Civil-Military Relations

In the analysis of group interactions and presence of social conflict, one must give attention to the social, communicative actions between groups (i.e., the military group, the political group, the social group). Military leaders gain experience as they move through the ranks of a very hierarchical organization. The military’s value is the expertise it has in its profession, giving the military “expert knowledge not available anywhere else” when applied to civil-military relations. Conflict occurs when military leaders enter or are drawn into political processes and the civil-military relationship is treated as two, distinct bodies.

Civil-military theory generally holds that the social group, at first, remains an interested bystander as the political and military groups interact, with conflict as a natural by-product. As the political and military groups seek power to bolster their respective positions over the conflict that led to dissent, the social group becomes embroiled in a pitched battle for power. Conflict reverberates outward from principal-agent, ultimately embroiling the social group.

The “sweet-spot” of civil-military relations occurs with the understanding that there are three groups in the equation. Conflict is inevitable, but is ultimately beneficial to organizations, even civil-military ones. While the social group’s location within civil-military relations can act as a power enhancer for the dissenting group, understanding the role of the citizenry in civil-military relations can be the salve that sustains the relationship.

Practitioners of security assistance and security cooperation should seek to operate in the sweet-spot as depicted in Figure 1. This is not to denigrate security cooperation programs that focus primarily on promoting strictly military-to-military contacts, but other institutions recognize the increased civil role in security assistance and security cooperation. For example, the Center for Civil-Military Relations seeks to build partner capacity and improve interagency and international cooperation by addressing civil-military challenges. These challenges include enhancing civil-military relations and defense institution building, among others. The Management of Security Cooperation (Green Book) of DISCS notes the role of civilian (not necessarily political) managers of defense establishments in promoting military justice, codes of conduct, and the protection of human rights.

Figure 1. The “sweet spot” of civil-military relations.

Civil-military literature previously characterized civil-military relations as occurring between two groups: the political and the military. Huntington called civil-military relations “a complex balancing act between the two groups.” He may be correct. While other civil-military theorists support the diumvirate, describing the civil-military relationship as “principal-agent,” it is regrettable that civil-military literature has focused on the hierarchy of the two groups, a subservient military serving the political group. More research supporting the view of Saas and Hall and Martin is required, as these authors rightfully add the social group to the political and military groups. Civil-military literature has either skirted the importance of the social group or overlooked the social group entirely. This has serious implications for managing security cooperation.

As the political and military groups seek power to bolster their respective positions, the social group becomes embroiled in the power struggle. Such an understanding supports a basic conclusion about dissent theory: it is helpful in understanding organizations and group development.

Given the proclivities of today’s society to take sides over any issue, civil-military relations will continue to be a rocky road. Society will be increasingly involved in civil-military relations in the Twitter Age. More research is required to fully understand the role society plays in civil-military relations and what the ramifications are for practitioners of security cooperation.

About the Author

Dr. David A. “DAM” Martin, Ed.D is a retired Eurasian FAO , and is currently an instructor at the Defense Institute for Security Cooperation Studies. His prior assignments include SDO/DATT Tajikistan (2000-01) and several high-level assignments on the DoD staff.