The Strategic Advisor: Charting a Path from Concept to Reality

By Colonel Mark Sturgeon, U.S. Army

(Image: United States European Command courtesy photo by Tomislav Brandt, Croatia Ministry of Defense)

Disclaimer: The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. The U.S. Army War College is accredited by the Commission on Higher Education of the Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools, an institutional accrediting agency recognized by the U.S. Secretary of Education and the Council for Higher Education Accreditation.

The Strategic Advisor: Charting a Path from Concept to Reality

There is little doubt that the U.S. Army recognizes the need to develop leaders who can effectively advise senior decision-makers on matters of strategic importance. Indeed, the U.S. Army War College (USAWC) touts that its graduates “[p]rovide strategic context and perspective to inform and advise national-level leaders -- providing sound, nuanced and thoughtful military advice.”[1]In addition to its standard resident course of instruction designed to prepare students for service at the strategic level, USAWC offers special programs which focus on developing strategically-minded thinkers, including the National Security Policy Program and the Advanced Strategic Art Program, the latter of which explicitly seeks to produce "strategic advisors."[2]

Despite the Army’s emphasis on ensuring its senior leaders have the capability to advise decision-makers within the national security establishment, the Service has not formally defined what this advisory role entails. No single, authoritative Army policy or regulation defines the specific qualifications or competencies required to serve in an advisory capacity at the strategic level. Similarly, the Joint Force offers no clear direction to the Services regarding such qualifications and competencies. Based on the lack of official guidance on the roles and qualifications of a “strategic advisor,” one can surmise that the Army views this duty as just one of several that its senior leaders must be able to perform, regardless of position or formal responsibilities—a kind of universal additional duty.

While the Army expects senior leaders to think and operate effectively at the strategic level, this paper argues that strategic-level advising requires specific expertise and experience beyond the professional military education provided by the Army War College and other Senior Service Colleges. It further asserts that the Army should seek to create a cadre of strategic advisors and employ them in designated positions where they can most impact the development and implementation of national security policy and strategy. The paper also argues that the ideal population from which to draw this cadre exists in the Army’s Foreign Area Officer (FAO) Corps, the Service’s “premier U.S. defense and security policy experts.”[3]

To support the above arguments, the paper first defines the role of the Army strategic advisor and explains how the strategic advisor contributes to the formulation and effective implementation of national security policy and strategy. It includes a model illustrating how the strategic advisor can and should fit into the process of effecting desired change in the strategic environment. The paper then examines the Army’s accession, training, utilization, and management of FAOs to demonstrate why they are ideal candidates to meet the Service’s need for strategic advisors. Finally, the paper presents several recommendations on how the Army, drawing upon the expertise and experience resident in its FAO Corps, should develop, manage, and employ a cadre of strategic advisors.

The Strategic Advisor

What exactly is the role of a strategic advisor? As previously noted, official Army and joint publications do not provide a clear answer to this question. The term “strategic advisor” appears to be most strongly associated with the corporate world, and one can find advice on developing the skills and attributes to serve as a strategic advisor in business literature. However, the limited body of literature addressing this topic devotes little effort to clearly defining the role of the strategic advisor. According to Patrick M. Wright et al. in the book The Chief HR Officer: Defining the New Role of Human Resource Leaders, “the strategic advisor role consists of all activities that focus on attempting to influence the strategy of the firm.”[4] While succinct and reasonably accurate, such a broad and imprecise definition has little value in describing the role of the strategic advisor in the military context.

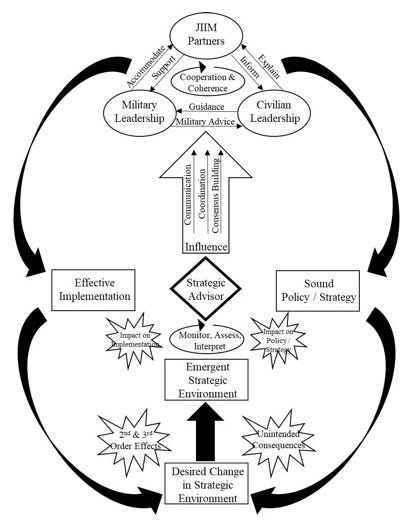

To make the case for the importance of properly developing and employing strategic advisors, the Army must clearly articulate what they need to do. To that end, this paper defines Army strategic advisors as officers possessing extensive expertise, training, and experience in political-military affairs, suited for service in select advisory positions to enable the formulation and successful implementation of sound national security policy and strategy. Figure 1 builds on this definition by depicting the integral role of the notional strategic advisor in policy/strategy formulation and implementation.

(Figure 1)

The model depicts the strategic advisor engaging in the strategic appraisal process, assessing the strategic environment in the context of national interests and developing an understanding of the key strategic factors at play.[5] Guided by this understanding, the strategic advisor influences senior Department of Defense (DoD) leaders, both civilian and military, as well as Joint, Interagency, Intergovernmental, and Multinational (JIIM) partners through communication, coordination, and consensus building. The strategic advisor’s influence helps facilitate constructive interaction and ameliorate impediments to cooperation among these actors, thereby enabling the formulation and effective implementation of sound national security policy and strategy. The strategic advisor continuously assesses the resulting change in the strategic environment, encompassing desired outcomes, effects over time, and unintended consequences, as well as the impact of this change on the validity and implementation of the catalyzing policy or strategy, as part of the aforementioned strategic appraisal process. The circular form of the model shows how outputs and inputs overlap and captures the non-linear nature of the strategic advisor's work, which requires the constant and concurrent applications of environmental scanning, strategic appraisal, and influence activities. The model is further examined below.

Making Sense of the Strategic Environment

One of the essential tasks of the Army strategic advisor is to help senior U.S. government leaders interpret and manage the strategic environment in which they operate. High levels of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity characterize the environment.[6] The formulation and effective implementation of sound policy and strategy requires an exceptional understanding of the various forces at play in the strategic environment and how they affect the interests and behavior of key actors. From the DoD perspective, the most salient aspects of the strategic environment include security threats, international alliances, the federal budget, public opinion, the military-industrial complex, technology, the rest of the federal government, and the internal environment.[7] The strategic advisor should “understand these elements and monitor them while helping to guide the organization through this ever-changing environment.”[8]

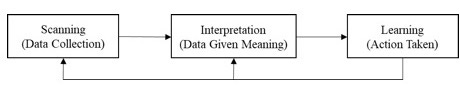

Comprehending the strategic environment requires more than simply keeping abreast of current events and assessing their impact on one’s organization, however. Richard L. Daft and Karl E. Weick conceptualize organizational interpretation of the external environment as a three-stage process in which scanning (stage 1), interpretation (stage 2), and learning (stage 3) are interconnected through a feedback loop, as shown in figure 2.[9] In this process, one collects data (scanning) and gives it meaning (interpretation), which then serves as the basis for organizational action (learning). The ability to accurately interpret data to inform policy and strategy requires impeccable judgment and extensive knowledge of the strategic environment. This competency is critical for the strategic advisor if one accepts that interpretation is “the unique responsibility of the senior leader.”[10]

(Figure 2)

Assigning meaning to information gathered through environmental scanning is central to the strategic appraisal process, which seeks to “quantify and qualify what is known, believed to be known and unknown about the strategic environment in regard to a particular realm of strategy and identify what is important with regard to such strategy’s formulation.”[11] This step involves assessing information in the context of strategic interests to determine key strategic factors—those factors which serve as the basis for a strategy’s ends, ways, and means.[12] Realizing success in this challenging task requires the strategic advisor to possess proficiency in applying strategic thinking competencies, including critical thinking, creative thinking, systems thinking, thinking in time, and ethical thinking.[13]

Exercising Influence Through Communication, Coordination, and Consensus Building

Regardless of how well one can interpret the strategic environment, the Army strategic advisor will not be successful unless also able to translate their interpretation into meaningful decisions and appropriate actions. Doing so requires the strategic advisor to exercise influence over key stakeholders, including senior civilian and military DoD leaders and JIIM partners, involved in the process of formulating and implementing policy and strategy. The strategic advisor exercises such influence via various means of communication, coordination, and consensus building and, through these activities, fosters cooperation as well as policy/strategy coherence.

While the Army expects its senior officers to possess superior communication skills, the ability to communicate effectively is essential to the success of the strategic advisor. Besides understanding the external environment and how it impacts strategic interests, the strategic advisor must clearly articulate this knowledge and convey their recommendations for decisions and actions to ensure that policy/strategy is advancing these interests in light of environmental changes. The strategic advisor cannot force decisions or generate action unilaterally given the nature of their position in the military hierarchy and the lack of authority to direct JIIM partners. Rather, the strategic advisor must seek to persuade key stakeholders by presenting “evidence and a sound argument to prove what is proposed will actually contribute to solving identified problems.”[14]

While the Army strategic advisor uses communication to inform and persuade key stakeholders to obtain decisions and generate action, the purpose of coordination is to ensure that any decision or action taken to address a policy/strategic issue (or set of issues) is well-executed. Realizing effective coordination requires that the strategic advisor be thoroughly familiar with his/her organization’s internal processes, the equities of higher and subordinate headquarters, the interests and concerns of relevant JIIM partners, and the ways in which these actors interrelate with one another. Leveraging this knowledge enables the strategic advisor to facilitate shared understanding and unity of effort among key stakeholders. Through these efforts, the strategic advisor contributes to effective coordination across organizational lines, which is a prerequisite for achieving coherent policies and strategies.[15]

Given the differing perspectives and divergent preferences that often exist within DoD organizations and the JIIM environment, successful coordination on matters of policy/strategy generally requires a significant amount of consensus building. Indeed, consensus is "probably the most critical aspect of accomplishing national objectives during an interagency operation.”[16] The Army strategic advisor must therefore be adept at working with key internal and external stakeholders to build consensus for decisions and actions that advance U.S. strategic interests. This competency requires the strategic advisor to possess a profound appreciation of stakeholder viewpoints (i.e., empathy) and the nuances involved in the policy issues at play to determine trade space and areas of potential compromise.

Effecting Desired Strategic Outcomes Through Cooperation and Policy Coherence

As noted above, the Army strategic advisor’s application of influence through communication, coordination, and consensus building fosters cooperation among key stakeholders and policy coherence. The strategic advisor thus helps ameliorate sources of friction and misunderstanding that can hinder cooperation between distinct stakeholder groups and undermine collective efforts to address complex problems. These stakeholder groups include civilian DoD officials, senior uniformed leaders, and JIIM partners (e.g., the National Security Council, the State Department, foreign allies) that shape the crafting and implementation of U.S. policies and DoD strategies. Close cooperation among these actors and the resulting benefits in policy coherence contribute to the realization of desired strategic outcomes.

One way in which the strategic advisor fosters cooperation is by helping to bridge the civilian-military divide that exists in the U.S. national security establishment. Janine Davidson describes this divide as a "broken dialogue" in which differing expectations for civilian control of the military, combined with institutional and cultural factors, hinder effective decision-making regarding the use of military force.[17] A central feature of the broken dialogue is the “chicken and egg” dilemma wherein civilian leaders do not receive the advice they need from the military to provide useful guidance, and the military does not receive the guidance it needs from civilian leadership to provide useful advice.

Although this dilemma represents a wicked problem that defies an easy fix, the strategic advisor can help lessen its impact by leveraging interpersonal, communication, and empathic skills to serve as an effective conduit between civilian and uniformed stakeholders. The strategic advisor should, for instance, help articulate to uniformed stakeholders what the civilian leadership needs in terms of military advice, as well as translate military advice into information that civilian officials can use when making decisions. In addition, the strategic advisor should play an active role in explaining to civilian stakeholders the military’s critical guidance requirements and ensuring that their guidance enables the military to move forward with planning and execution.

The strategic advisor also facilitates cooperation between the DoD (both civilian and uniformed stakeholders) and JIIM partners. Such facilitation can take several forms. It might, for example, involve the strategic advisor working with foreign representatives to secure commitment to a strategy whose success is contingent upon the support of their nations. It might also involve negotiations with the U.S. Department of State on how best to implement a security cooperation program that contributes to the achievement of DoD strategic objectives but carries some risk from a foreign policy perspective. By virtue of their access, placement, and expertise, the strategic advisor can identify areas of common interest for both DoD and JIIM stakeholders and use them to generate support for the formulation and implementation of policies and strategies that account for U.S. defense policy goals while also accommodating the concerns and desires of JIIM partners.

The close cooperation among key stakeholders enabled by the Army strategic advisor contributes to coherence in U.S. policies and strategies. Guillermo Cujedo and Cynthia Michel define policy coherence as "the process where policymakers design a set of policies in a way that, if properly implemented, they can achieve a larger goal."[18] Coherence thus requires the government to ensure that policies and strategies are complementary and synergistic, as well as implemented in a coordinated and effective fashion. Such coherence is contingent upon the involvement of all stakeholder groups, with civilian leadership (both in DoD and elsewhere in the interagency) having the lead on policy and strategy formulation at the national level, while uniformed stakeholders, supported by JIIM partners, are primarily responsible for the implementation of these policies and strategies, as well as the development of subordinate strategies. Note that the model of the strategic advisor found in Figure 1 attempts to reflect this division of labor in the placement of the two arrows depicting policy/strategy formulation and implementation.

Ensuring Strategic Success Over Time

If properly implemented, sound policy/strategy has a reasonable chance of achieving the desired strategic outcome. However, the dynamic nature of the strategic environment, characterized by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity, means that the success of a given strategy is never certain and often not enduring. Sudden or gradual changes in the external environment can render an appropriate and well-implemented strategy less effective or even counterproductive. Policy priorities and interests can change over time, leading to divergence between the stated ends of a strategy and the strategic outcomes desired by the national security establishment.[19] A strategy's actual or perceived success or failure creates feedback that may serve as an impetus for revision or replacement.[20]

The outcomes brought about by the implementation of a given strategy, including unintended consequences and effects over time (i.e., second and third-order effects), along with unrelated changes to the external environment, create an emergent strategic environment. The strategic advisor, as part of an ongoing strategic appraisal process, must continuously monitor and assess this emergent environment and its impact on both the suitability and implementation of the strategy. Based on their interpretation of the environment, the strategic advisor must further determine whether observed and anticipated developments warrant adjustments to the strategy and/or its implementation, or potentially even a new strategy. This determination serves as the basis for the strategic advisor’s recommendations regarding decisions and actions that leaders should take to ensure that U.S. strategic interests are protected and advanced.

Why FAOs?

Given the unique responsibilities and requisite knowledge, skills, and attributes of the Army strategic advisor, developing an officer to fill this vital role must be a deliberate and selective process. Fortunately, in its FAO Corps, the Army already possesses a defined and specially managed population capable of providing a steady stream of candidates particularly well-suited to serve as strategic advisors. The accession, training and education, utilization, and management of FAOs create a deep talent pool from which to select and further prepare officers for such service. Each of these contributing factors, as well as the role of the Army FAO, are examined below.

The Role of the Army FAO

The DoD describes the members of the Joint FAO Corps as “strategic effects operators” who are uniquely positioned to serve at “the highest levels of strategic decision-making.”[21] The Army further defines its FAOs as the Service’s “premier U.S. defense and security policy experts with education, knowledge and skill sets relevant to regions and countries.”[22] The primary responsibilities of Army FAOs include advising senior civilian and military leaders, developing policy and providing political-military analysis as members of strategic and interagency staffs, and building the capacity of foreign partners through defense equipment sales and combined training.[23] The role and responsibilities of the Army FAO thus clearly overlap with those of the Army strategic advisor to a significant degree.

The conceptual overlap between the FAO and strategic advisor specialties is also apparent when considering the professional expertise required by each. According to the Department of the Army, the Service’s FAOs should possess the following knowledge, skills, and behaviors:

(1) A ready facility to express ideas and recommendations accurately, clearly, and concisely in both oral and written communication at the strategic level.

(2) The capability to synthesize and apply knowledge from multiple disciplines into a coherent overarching perspective.

(3) The ability to influence, persuade, lead, and be informed by diverse teams with wide-ranging perspectives.

(4) The ability to choose between best practices and unorthodox approaches to reach a solution.

(5) Flexibility to operate independently while implementing commander’s intent.

(6) Candor and moral courage to speak accurately, and truthfully, to senior leaders.

(7) Intellectual curiosity that drives a commitment to lifelong learning and professional and personal self-development.[24]

The strategic advisor obviously needs this same expertise to effectively execute his/her duties, to include conducting strategic appraisal and influencing key stakeholders. Indeed, the above list would serve as a great starting point for the Army to use in formally defining the characteristics of a strategic advisor.

Army FAO Accession and Training/Education

In accessing officers into the FAO Corps, the Army seeks to select those who have the potential to acquire and apply the requisite knowledge, skills, and behaviors. It does this primarily through the Volunteer Transfer Incentive Program (VTIP), in which a panel considers the applications of officers who wish to transfer into the FAO functional area from other Army branches.[25] The officers selected through this process have generally completed six to nine years of commissioned service at the tactical level, including a command assignment, and are thus quite familiar with the “operational” side of the Army. FAO branch selects approximately 40 percent of those who apply through VTIP, with the top discriminator in the selection being the strength of the applicant's previous performance evaluations.[26] The competitive nature of FAO accession and the requirement to have a solid grounding in the profession of arms prior to joining the FAO Corps contribute to making Army FAOs ideal candidates for service as strategic advisors.

The specific training and education that Army FAOs receive during their careers provide them with further advantages relative to other officers in terms of suitability for strategic advisor duty. Initial training and education for FAOs typically include a year spent in their respective geographical regions of specialization (e.g., Eurasia, Sub-Saharan Africa), during which they should gain an understanding of regional U.S. policy goals and formulation, the JIIM environment, international organizations, and theater security cooperation activities.[27] FAOs must also obtain a graduate degree in a professionally relevant discipline such as international relations, geopolitics, or national security studies.[28] In addition, Army FAOs will often have opportunities to participate in other training and education throughout their careers (e.g., courses offered by the Defense Security Cooperation University) and are expected to engage in continuous self-development to hone their skills in international relations as well as joint and expeditionary competencies.[29] The training and education afforded to Army FAOs provide a strong foundation from which to develop strategic advisors.

FAO Utilization

The purpose of the Army FAO Corps’ competitive selection process and extensive program of training and education is, of course, to produce officers capable of serving successfully in a variety of FAO assignments. The Army organizes FAO assignments into three categories: (1) overseas U.S. Embassy country team, which includes attaché and overseas security cooperation (SC) assignments; (2) Army operational/institutional, which includes assignments at Army Service Component Commands, the Army Staff, and Army academic institutions; and (3) political-military, which includes assignments at joint and non-DoD organizations, such as the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Joint Staff, and the National Security Council.[30] Over the course of their career, an Army FAO should complete assignments in multiple categories and, as a colonel, should have mastery of all of them.[31]

In addition to, and as part of serving in, these assignments, Army FAOs assist DoD by incorporating strategic understanding, SC knowledge, operational planning and regional expertise, and cultural awareness to serve as strategic effects operators…collaborating with other U.S. Government agencies and with foreign governments, non-governmental organizations, and intergovernmental organizations… [and] advancing U.S. strategic security interests through the development of professional competencies.[32]

Such competencies include “(1) the ability to operate worldwide in JIIM environments and leverage capabilities beyond the Army in achieving organizational objectives, (2) a sound understanding of interagency and non-governmental organizations' capabilities and their unique professional cultures, (3) [being] well-versed in U.S. foreign policy and regional security cooperation priorities.”[33]The nature of FAO assignments, which often require in-depth policy knowledge, close collaboration with JIIM partners, and routine interaction with senior civilian and military leaders to achieve strategic effects, points to professional experience that is invaluable for the would-be strategic advisor.

FAO Talent Management: Building the FAO Colonel

Through its professional development and career management policies and practices, the Army seeks to create FAO colonels who possess true regional expertise and can effectively apply it to advance Army, Joint Force, and U.S. Government priorities.[34]Such expertise does not merely involve detailed knowledge and understanding of one’s region of specialization (known as an “area of concentration” in Army FAO parlance). It also refers to one’s proficiency in “core culture competencies,” such as organizational awareness and cultural adaptability, as well as “leader/influence function competencies,” which include strategic agility, systems thinking, and the development of strategic networks.[35] As colonels, FAOs should have attained at least full proficiency, if not mastery, in each of these competencies.[36]

The development of FAO colonels is a lengthy and costly process, involving significant investment in training and education, as well as the acquisition of practical experience in a diverse array of assignments over many years. This deliberately managed process should lead to the development of strategically-minded officers comfortable operating in the JIIM environment and capable of exercising influence across organizational boundaries to effect strategic change. It is difficult to conceive of a more qualified population from which the Army could draw to build and sustain a cadre of strategic advisors.

From FAO to Strategic Advisor

While Army FAO colonels are well-positioned to fill the need for Army strategic advisors, not all are qualified or suited for strategic advisor duty simply by virtue of their career field and seniority. A formal qualification process, additional professional development, and focused talent management would help ensure that the Army selects and effectively utilizes as strategic advisors only those FAO colonels with the greatest potential and desire to serve in this capacity. Moreover, maximizing the value that FAOs could provide as strategic advisors would require the Army to make changes to its force structure and assignment policies and practices by designating the specific billets that they should fill. The below recommendations describe in further detail the steps that the Army should take to create and effectively utilize a strategic advisor cadre.

Qualifying and Managing FAOs as Strategic Advisors

To qualify as a strategic advisor, a FAO should possess a mix of experience that fosters strategic thinking, an understanding of the JIIM environment, and the ability to communicate and cooperate effectively with key stakeholders. This mix should thus include a joint duty assignment, a political-military assignment, and an assignment involving routine interaction with interagency and foreign partners. Given the importance of security cooperation as a tool for advancing U.S. security interests in today’s competitive strategic environment, completion of a security cooperation assignment should also be a requirement. By the time a FAO is a colonel, they will almost certainly have acquired the requisite experience, particularly since an average FAO assignment can check several blocks simultaneously. For instance, an assignment to an overseas security cooperation office would likely satisfy three of the four experience requirements (joint duty, security cooperation, routine interaction with interagency and foreign partners).

In addition to meeting the basic experience qualifications, strategic advisors sourced from the FAO Corps should be graduates of a Senior Service College (SSC) resident program. Completion of a resident SSC course of study would provide a deeper understanding of the art of strategy formulation, the policymaking process, the functioning of the U.S. national security enterprise, and the nature of strategic-level leadership, as well as opportunities to refine communication skills and gain insights into the most salient defense and foreign policy issues. Combined with the joint duty experience required of a FAO seeking to become a strategic advisor, it would also provide the credentials necessary for designation as a Joint Qualified Officer, a key qualification for service at the strategic level.[37]

Finally, qualification as a strategic advisor should be contingent upon successfully completing the Colonels Command Assessment Program (CCAP). Although CCAP is generally associated with the assessment and selection of officers for brigade-level command, it is also used to determine readiness to serve in non-command key billets and is specifically designed to assess participants' "strategic potential.”[38] Given that the roles and competencies of a strategic advisor remain largely the same across different organizations and areas of responsibility, FAOs who satisfy this prerequisite would be eligible to serve in multiple strategic advisor assignments over the remainder of their careers without having to go through the CCAP process again.

By including strategic advisor positions among the key billets reserved for officers certified through the CCAP process, the Army would help ensure that the FAOs who fill these billets have a similar profile as non-FAOs selected for senior positions. This would have the additional benefit of bolstering the credibility of strategic advisors in the eyes of peers and superiors from the “operational force” with whom they would interact. Furthermore, the requirement to “opt in” the selection process for CCAP attendance would ensure that only those FAOs interested in serving as strategic advisors would have the opportunity to do so.

To track and manage its cadre of strategic advisors, the Army should create an Additional Skill Identifier (ASI) reserved for FAOs who have met the aforementioned qualifications. The FAOs thus identified as qualified would be eligible to serve in billets specifically coded for qualified strategic advisors in addition to standard FAO billets.

Effectively Utilizing FAOs as Strategic Advisors

Optimal use of strategic advisors would require changes to the Army's existing force structure and assignment policies and practices. As noted above, certain billets should be designated specifically for FAOs awarded the strategic advisor ASI. Such billets should encompass Army-sourced Senior Defense Official/Defense Attaché positions in countries that play a particularly significant role in U.S. foreign and defense policy, whether globally or regionally. This category should also include all colonel-level positions at the National Security Council, the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Policy, the Joint Staff, and each Geographic Combatant Command headquarters that are coded for Army FAOs.

Furthermore, the Army should seek to recode for strategic advisor-qualified FAOs certain positions that are not currently reserved for FAOs. Examples include Army-sourced division chief positions in the Joint Staff J5 regional deputy directorates, very few of which are currently coded for FAOs, as well as Commander’s Initiatives Group / Commander’s Action Group director positions in Army Service Component Commands.[39] Such an expansion in FAO colonel billets would require an increase in the overall size of the FAO Corps and create difficult tradeoffs, as it would potentially require a reduction in officer force structure elsewhere and certainly diminish the opportunities for officers from other branches and functional areas for broadening assignments in key billets. However, the value strategic advisors would bring to the Army and the Joint Force in these positions would justify the attendant costs and tradeoffs.

The Army should also seek to fill select General Officer (GO) billets with FAOs qualified as strategic advisors. The Army often selects GOs from the “operational force” for senior staff positions concerned primarily with strategy and policy, such as J-5 director and deputy director billets on the Joint Staff and in Geographic Combatant Commands. While these officers are certainly capable of serving effectively in such positions, the Army should view its strategic advisor cadre as the preferred source of candidates to fill them. The relatively small size of the FAO Corps and the low selection rates for promotion to and within the GO ranks, regardless of branch/functional area, would likely preclude all such billets from being filled exclusively by strategic advisors. However, the aforementioned growth of FAO colonel billets would help to mitigate this constraint. Furthermore, the increased opportunity for FAOs to serve at the GO level would likely coincide with higher GO promotion rates within the FAO Corps given the stringent qualification criteria for strategic advisors.

Addressing Bureaucratic and Cultural Obstacles

The implementation of these recommendations for establishing and utilizing a cadre of strategic advisors sourced from the FAO Corps would undoubtedly create consternation within the Corps and among other Army stakeholders. Human resource managers are often reluctant to assign junior FAO colonels to the most demanding assignments based on a belief that these officers must first prove themselves in "easier" colonel-level assignments. By not assigning the most capable FAO colonels to key billets as soon as possible, the Army underutilizes their talent and fails to gain the maximum return on the Service's investment in them.[40]The force structure changes and rigorous selection process for strategic advisors described above help prevent such underutilization by enabling, respectively, the identification of the most critical FAO billets and the officers best qualified to fill them. Proponents of the strategic advisor concept should emphasize its benefits in terms of FAO talent management to garner the support of those responsible for colonel assignments in the FAO Corps. This effort should also seek to foster a greater appreciation for the importance of enterprise-level staff assignments and other non-embassy assignments for FAO professional growth and career progression.

Beyond the potential bureaucratic and cultural resistance within the FAO Corps, other Army branches and functional areas would likely object to the implementation of the strategic advisor concept as described due to the recommended force structure and assignment policy/practice changes that would reduce the opportunities for their officers to serve in key senior staff positions. In response, proponents of the concept could consider compromising on the proposal to code select staff positions on the Joint Staff and elsewhere exclusively for FAOs qualified as strategic advisors. The continued assignment of officers from other branches/functional areas to these positions would prevent the Army from realizing the full benefit of its strategic advisor cadre, but not to an unacceptable degree, particularly if it gave strategic advisor-qualified FAOs priority in the assignment process. Indeed, the challenges inherent in maintaining a sufficiently manned strategic advisor cadre would likely require the Army to fill these billets with other officers on a regular basis anyway.

Bridging the Gap

Although the Army acknowledges the importance of having senior officers capable of providing strategic-level advice, it lacks a deliberate, formal process for developing, certifying, and managing talent to perform this critical function. The gap between what the Army says it wants from its officer corps and what it actually does to realize this aspiration is clearly illustrated by the fact that the role of a strategic advisor is not defined in Army policy or regulation. While the Army promotes the virtues of joint duty experience and provides its senior leaders with PME opportunities designed to foster strategic thinking and an understanding of the JIIM environment, these efforts alone do not ensure competency in strategic advising.[41] As a result, the Army is not leveraging its human resources as effectively as it otherwise could to effect strategic change for the benefit of the Service, the Joint Force, the Department of Defense, and the nation.

This paper attempts to address the gap first by clearly defining and modeling the roles and responsibilities of the Army strategic advisor, as well as describing the essential skills and expertise required of an effective strategic advisor. It further seeks to explain why the FAO Corps serves as an ideal talent pool from which to create a strategic advisor cadre and suggests steps the Army should take to develop, manage, and utilize strategic advisors sourced from the FAO Corps. While not providing a perfect or comprehensive solution, the ideas presented in this paper can serve as a useful starting point for an Army effort to maximize the value and impact of its senior officers who serve in an advisory capacity at the strategic level. The Army must undertake such an effort if it is to leverage its full potential to enable the U.S. government to successfully manage the challenges facing the nation in the volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous strategic environment of today and the future.

About the Author

Colonel Mark Sturgeon is a U.S. Army Europe/Eurasia Foreign Area Officer with significant experience in the USEUCOM AOR. In June 2023 he assumed duties as U.S. Army Attaché to the Netherlands. His prior FAO assignments included South Caucasus Country Director at the Office of the Secretary of Defence (OSD Policy), Chief of the Office of Defense Cooperation in Slovakia, and Assistant Army Attaché in Poland. He completed the U.S. Army War College in June 2023.

END NOTES

[1] “MEL-1 Resident Education Program,” U.S. Army War College, https://ssl.armywarcollege.edu/rep.htm.

[2] “The Army War College Experience,” U.S. Army War College, ttps://www.armywarcollege.edu/experience/seminarExperience.cfm#four.

[3] Department of the Army, Officer Professional Development and Career Management, DA PAM 600-3 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2021), 23-1 https://api.army.mil/e2/c/downloads/2022/08/03/8dc3f824/1-fa-48-foreign-area-officer-da-pam-600-3-as-of-23-apr-21.pdf

[4] Patrick M. Wright et al., The Chief HR Officer: Defining the New Role of Human Resource Leaders (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2011), 42.

[5] H. Richard Yarger, Strategic Appraisal: The Key to Effective Strategy, vol. 1 of U.S. Army War College Guide to National Security Issues, 4thed., ed. J Boone Bartholomees Jr. (Carlisle Barracks, PA: U.S. Army War College, Strategic Studies Institute, 2010), 53.

[6] T. Owen Jacobs, Strategic Leadership: The Competitive Edge, (Washington, DC: National Defense University, 2009), 11.

[7] Rod McGee, Murray Clark, and Craig Bullis, “The Strategic Leadership Environment (faculty paper, U.S. Army War College, Department of Command, Leadership, and Management, Carlisle Barracks, PA, 2021), 5.

[8] McGee, Clark, and Bullis, 5.

[9] Richard L. Daft and Karl E. Weick, “Toward a Model of Organizations as Interpretation Systems,” Academy of Management Review 9, no. 2 (April 1984): 286.

[10] Craig Bullis, “An Interpretive Model of Managing the External Environment,” (working paper, U.S. Army War College, Department of Command, Leadership, and Management, Carlisle Barracks, PA, 2015), 4.

[11] Yarger, Strategic Appraisal: The Key to Effective Strategy, 53.

[12] Yarger, 58.

[13] Yarger, 61.

[14] William J. Davis, Jr., “The Challenge of Leadership in the Interagency Environment,” Military Review 90, no. 5 (Sep/Oct 2010): 96.

[15] Guillermo M. Cujedo and Cythia L. Michel, “Addressing Fragmented Government Action: Coordination,

Coherence, and Integration,” Political Science 70 (2017): 754.

[16] Davis, “The Challenge of Leadership in the Interagency Environment,” 96.

[17] Janine Davidson, “Civil-Military Friction and Presidential Decision Making: Explaining the Broken Dialogue,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 43, no. 1 (March 2013): 129-145.

[18] Cujedo and Michel, “Addressing Fragmented Government Action: Coordination, Coherence, and Integration,” 755.

[19] J. Boone Bartholomees, Jr., ed., U.S. Army War College Guide to National Security Issues, (Carlisle Barracks, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2012), 2:417.

[20] Sam Sarkesian, John Allen Williams, and Stephen J. Cimbala, U.S. National Security: Policymaker, Policies, and Politics (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2013), 202.

[21] Department of Defense, Management of the DoD Foreign Area Officer Program, DoD Instruction 1315.20 (Washington DC: Department of Defense, 2022), 11, https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/131520p.pdf

[22] Department of the Army, Officer Professional Development and Career Management, 23-1.

[23] U.S. Army Human Resources Command Foreign Area Officer Branch, “FAO Tome of Knowledge,” (PowerPoint presentation, distributed to U.S. Army FAO population via e-mail on October 25, 2022).

[24] Department of the Army, Officer Professional Development and Career Management, 23-1.

[25] Department of the Army, 23-3.

[26] U.S. Army Human Resources Command Foreign Area Officer Branch, “FAO Tome of Knowledge.”

[27] Department of the Army, Officer Professional Development and Career Management, 23-6.

[28] Department of the Army, 23-6 – 23-7.

[29] Department of the Army, 23-9.

[30] Department of the Army, 23-3.

[31] Department of the Army, 23-11.

[32] Department of Defense, Management of the DoD Foreign Area Officer Program, 12.

[33] Department of the Army, Officer Professional Development and Career Management, 23-1.

[34] U.S. Army Human Resources Command Foreign Area Officer Branch, “FAO Tome of Knowledge.”

[35] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Language, Regional Expertise, and Culture Capability Identification, Planning, and Sourcing, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction 3126.01B (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2020), H-1, https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Library/Instructions/CJCSI%203126.01B.pdf?ver=UAzs6l7A8qVx_3DQ6Er7-Q%3d%3d.

[36] Department of the Army, Officer Professional Development and Career Management, 23-4, 23-11; Joint Chiefs of Staff, Language, Regional Expertise, and Culture Capability Identification, Planning, and Sourcing, I-1.

[37] Drew Lanier, “The Strategic Importance of Joint Qualification,” LinkedIn Pulse, June 13, 2022, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/strategic-importance-joint-qualification-/?trackingId=6pNLb4hcoJY4vd0ucsplcQ%3D%3D.

[38] “Colonels Command Assessment Program Begins in September,” U.S. Army War College News Archives, July 9, 2020, https://www.armywarcollege.edu/news/Archives/13642.pdf.

[39] “All Authorizations,” U.S. Army Human Resources Command, accessed January 24, 2023, https://aim.hrc.army.mil/portal/officer/portal.aspx.

[40] Ian Murray, e-mail to author, February 13, 2023.

[41] Lanier, “The Strategic Importance of Joint Qualification.”

Bibliography

Bartholomees, J. Boone, Jr., ed. U.S. Army War College Guide to National Security Issues. 5th ed. Carlisle Barracks, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2012.

Bullis, Craig. “An Interpretive Model of Managing the External Environment.” Working paper, U.S. Army War College, Department of Command, Leadership, and Management. Carlisle Barracks, PA, 2015.

Cujedo, Guillermo M. and Cythia L. Michel. “Addressing Fragmented Government Action: Coordination, Coherence, and Integration.” Political Science 70 (2017): 745-767.

Daft, Richard L. and Karl E. Weick. “Toward a Model of Organizations as Interpretation Systems.” Academy of Management Review9, no. 2 (April 1984): 284-295.

Davidson, Janine. “Civil-Military Friction and Presidential Decision Making: Explaining the Broken Dialogue.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 43, no. 1 (March 2013): 129-145.

Davis, William J., Jr. “The Challenge of Leadership in the Interagency Environment.” Military Review 90, no. 5 (Sep/Oct 2010): 94-96.

Department of the Army. Officer Professional Development and Career Management. DA PAM 600-3. Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2021. https://api.army.mil/e2/c/downloads/2022/08/03/8dc3f824/1-fa-48-foreign-area-officer-da-pam-600-3-as-of-23-apr-21.pdf.

Department of Defense. Management of the DoD Foreign Area Officer Program. DoD Instruction 1315.20. Washington DC: Department of Defense, 2022. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/131520p.pdf

Jacobs, T. Owen. Strategic Leadership: The Competitive Edge. Washington, DC: National Defense University, 2009.

Joint Chiefs of Staff. Language, Regional Expertise, and Culture Capability Identification, Planning, and Sourcing. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction 3126.01B. Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2020. https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Library/Instructions/CJCSI%203126.01B.pdf?ver=UAzs6l7A8qVx_3DQ6Er7-Q%3d%3d.

Lanier, Drew. “The Strategic Importance of Joint Qualification.” LinkedIn Pulse, June 13, 2022. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/strategic-importance-joint-qualification-/?trackingId=6pNLb4hcoJY4vd0ucsplcQ%3D%3D.

McGee, Rod, Murray Clark, and Craig Bullis. “The Strategic Leadership Environment.” Faculty paper, U.S. Army War College, Department of Command, Leadership, and Management. Carlisle Barracks, PA, 2021.

Sarkesian, Sam, John Allen Williams, and Stephen J. Cimbala. U.S. National Security: Policymaker, Policies, and Politics. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2013.

U.S. Army Human Resources Command. “All Authorizations.” Accessed January 24, 2023. https://aim.hrc.army.mil/portal/officer/portal.aspx.

U.S. Army Human Resources Command, Foreign Area Officer Branch. "FAO Tome of Knowledge." PowerPoint presentation, distributed to the U.S. Army FAO population via e-mail on October 25, 2022.

U.S. Army War College. “MEL-1 Resident Education Program.” Accessed November 13, 2022. https://ssl.armywarcollege.edu/rep.htm.

U.S. Army War College. “The Army War College Experience.” Accessed November 13, 2022. https://www.armywarcollege.edu/experience/seminarExperience.cfm#four.

U.S. Army War College News Archives. “Colonels Command Assessment Program Begins in September.” July 9, 2020. https://www.armywarcollege.edu/news/Archives/13642.pdf.

Wright, Patrick M., John W. Boudreau, David Pace, Libby Sartain, Paul McKinnon, Richard Antoine. The Chief HR Officer: Defining the New Role of Human Resource Leaders. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

Yarger, Richard H. Strategic Appraisal: The Key to Effective Strategy. Vol. 1 of U.S. Army War College Guide to National Security Issues, 4th ed., edited by J Boone Bartholomees Jr. Carlisle Barracks, PA: U.S. Army War College, Strategic Studies Institute, 2010.