Strengthening Alliances: Through the Joint Capabilities Integration and Design System

By Lieutenant Colonel Bryan “Buster” Shoupe, U.S. Air Force; Lieutenant Commander Cindy Suárez Villafañe, U.S. Navy; and Major Joseph Yurkovich, U.S. Army

Defense acquisition programs constantly draw negative attention, usually regarding cost overruns, missed milestones, and non-operational systems reliant on unproven technologies.

Headlines suggest the system is completely broken and in need of an overhaul. Despite such concerns, the current Defense Acquisition System (DAS), comprised of the requirements, acquisition and budgeting processes, helped create the world’s most powerful military. Still, the need for constant improvement of the DAS demands careful consideration of opportunities to simultaneously increase lethality and lower cost. Any improvement must also help achieve national security objectives with regard to Great Power Competition.

The 2018 National Defense Strategy presented eleven defense objectives to guide the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) in the era of Great Power Competition. The Secretary of Defense also provided the strategic approach to further those ends, including a line of effort to strengthen alliances and attract new partners. In those regards, multinational co-development of interoperable defense systems is an integral facet of strengthening and building relationships. The Joint Capabilities Integration and Design System (JCIDS) process, the requirements phase of the DAS, plays an integral part in ensuring interoperability as a capability requirement for the Joint Force. Despite the important role of JCIDS with regard to the Joint Force, there is no mechanism which allows allies and partners to directly participate and ensure interoperability with their systems is given appropriate consideration. The limitations to allied and partner participation in the JCIDS process prevent the Joint Force from capitalizing on opportunities to strengthen alliances, attract new partners, ensure interoperability, and benefit from economies of scale.

Our research shows that ally and partner participation in the JCIDS process is completely restricted, and that interoperability between their weapon systems and those of the Joint Force is often considered too late in the weapon development lifecycle. On the other hand, taking a multinational approach to defense acquisition programs can complicate development. In the JCIDS process, none of the current six acquisition pathways allow ally and partner participation, while only one pathway considers interoperability as a Joint Force capability requirement. Allies and partners participate in the F-35 acquisition program to varying degrees, but the sharing of their flight data with the U.S. and contractors as well as interoperability problems with older fighter platforms continue to complicate the program. Additionally, the Eurofighter showed promise as a multinational, co-development platform but the program suffered from too many competing capability requirements. Lastly, the U.S. Air Force’s T-X Advanced Pilot Training (APT) system-of-systems has failed to capitalize on potential economies of scale and interoperability capabilities by not including allies and partners in the process. In order to reorient the DAS to allow the DOD to strengthen alliances and build partnerships, allies and partners need to directly participate in the JCIDS process so that their capability requirements are given consideration at the earliest stages of capability requirement and weapon system development.

Points of Opportunity in the JCIDS Process

JCIDS is designed as the initial stage of development for integrating Joint Force capability requirements in order to develop future weapon systems. JCIDS incorporates input from across the services to ensure capability gaps are addressed and to inform weapon system developers of the need to initiate, continue, or modify product development.

The primary objective of JCIDS is to ensure Joint Force capability requirements are identified and validated. Before any requirement enters the JCIDS process, sponsors, usually the Combatant Commands, identify gaps and capability requirements related to their function, mission, and operational needs. In order to validate capability gaps and provide recommended solutions, a Capabilities Based Assessment (CBA) evaluates the capacity of the Joint Force to complete its missions and ensures traceability to strategic guidance documents. The CBA provides the basis for the Initial Capabilities Document (ICD), which documents the need for a materiel, non-materiel, or combination of both solutions to address a specific capability gap. In cases requiring a materiel solution, the ICD directs capability requirements to enter the defense acquisition lifecycle process. Allies and partners are not permitted to participate in the CBA or ICD. Figure 1 is a flowchart that determines material or non-material acquisition routes.

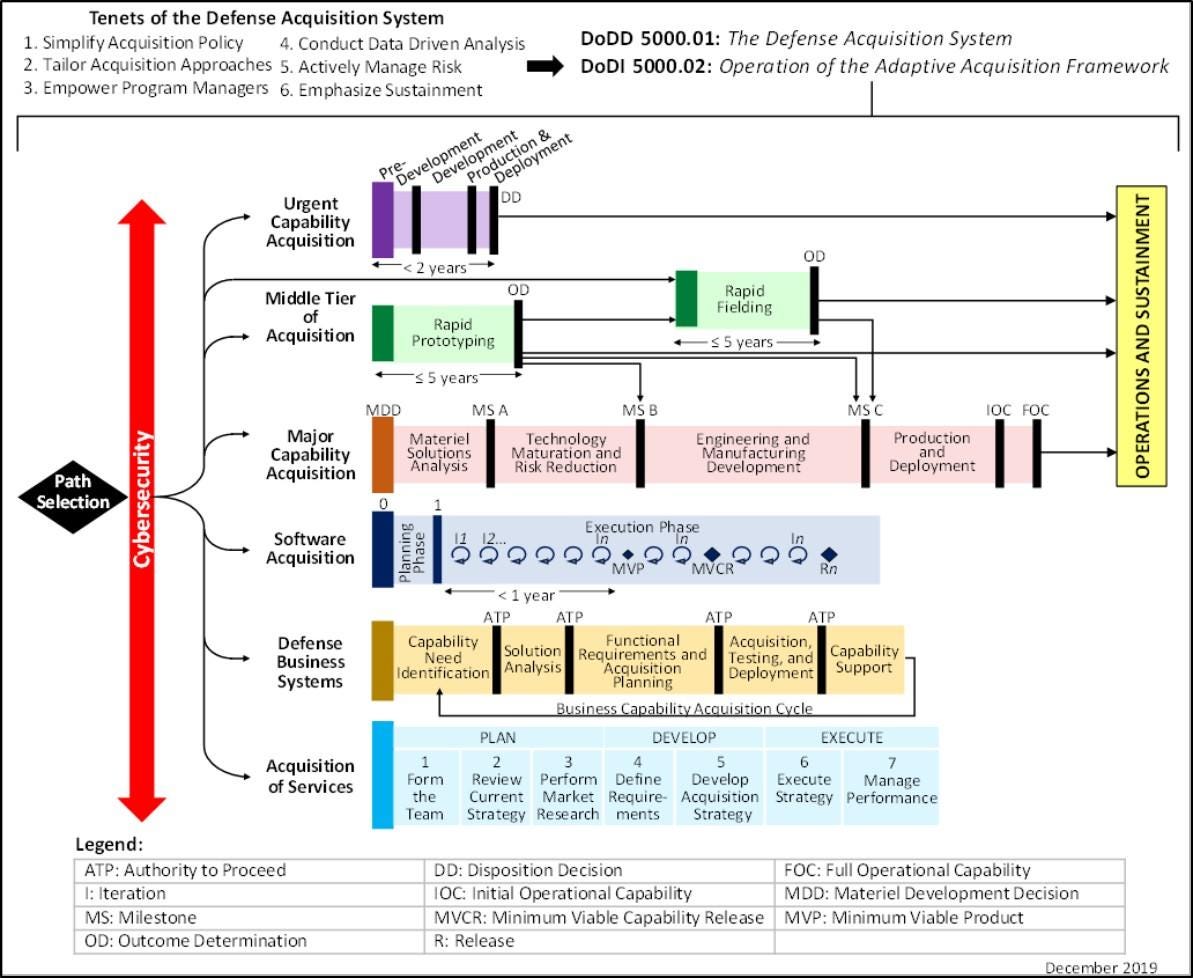

Until recently, the JCIDS had three process lanes to get capabilities to the Joint Force: Ongoing Contingency, Anticipated Contingency, and Deliberate. Realizing that solutions for capability gaps were not getting to warfighters in a timely manner, the DOD enacted the Adaptive Acquisitions Framework (AAF) in January 2020. The AAF expanded the process lanes to six acquisition pathways. The six pathways now provide program managers additional tools to meet the triple constraints – cost, schedule, and performance – and tailor acquisition strategies to best meet the needs of the Joint Force. The six acquisition pathways are: Urgent Capability Acquisition (UCA), Middle Tier of Acquisition (MTA), Defense Business Systems (DBS), Acquisition of Services, Major Capability Acquisition (MCA), and Software Acquisition. Figure 2, below, shows the AAF acquisition pathways and timelines associated with each.

The UCA pathway allows for rapid response to Joint Force urgent or anticipated emergent capability requirements for current or anticipated contingency operations if such capabilities are not available through the Global Force Management (GFM) process. To source a solution to address an urgent capability gap, Combatant Commands must submit a Joint Urgent Operational Need (JUON), Urgent Operational Need (UON), or Joint Emergent Operational Need (JEON) via their component command to the Director, Joint Rapid Acquisition Cell (JRAC), for validation. Both urgent and emergent requirements are expedited and JCIDS staffing timelines range from 15 to 120 days. Acquisition requirements fielded using this pathway are all driven by Combatant Commanders and do not offer any opportunities for ally or partner input.

The MTA pathway is used to develop prototypes rapidly and to field and demonstrate new capabilities in matured systems requiring minimal development. The MTA pathway allows new capabilities to be fielded to warfighters within five years, as well as to provide an on/off ramp option to accelerate acquisition programs before transitioning to a different acquisition pathway. “Per DOD guidance, defense

acquisition programs that progress through the MTA pathway are not subject to the JCIDS process and are limited to only the U.S. Joint Force.”

The DBS pathway is used for the acquisition of information systems that support DOD operations. Systems that can be acquired through the DBS pathway include logistics, human resources, financial, planning and budget, contracting, installation management, training, and “non-developmental, software intensive programs that are not business systems.” The DBS pathway aims to identify existing, successfully tested, commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) software, that can be adopted and customized to satisfy DOD needs. The DBS pathway does not allow ally or partner nation input as it is only utilized for the acquisition of DOD business systems.

The Acquisition of Services pathway is leveraged to contract services from the private sector to include cell phones, transportation, logistics, facilities, construction, electronics/ communication, and research and development. This pathway does not allow ally or partner input as it is used for the sustainment of operations of only DOD units, organizations, and installations. Altogether, the UCA, MTA, DBS, and Acquisition of Services pathways have no standing requirements or opportunities for ally or partner participation.

The MCA pathway is intended for major defense acquisition programs, systems, and complex acquisitions that provide enduring capabilities. It requires interoperability between both the Joint Force and coalition partners. How interoperability is achieved during MCA, however, is nebulous as coalition partners participate in the process by exception. Due to the technologically advanced, complex nature of acquisition programs developed through the MCA pathway, such programs regularly progress in parallel along the Software Acquisition pathway. Interestingly, the Software Acquisition pathway for software-only systems is not subject to the JCIDS process “except pursuant to a modified process specifically provided for the acquisition or development of software by the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.”

The complexity, magnitude, and service life of acquisitions programs which develop along the MCA pathway provide opportunities to directly address NDS lines of effort. To expand the competitive space by strengthening alliances and attracting new partners, the MCA presents an opportunity to increase ally and partner cooperation and co-develop major defense acquisition programs. The remaining acquisition pathways, wholly absent of interoperability or ally participation requirements, present opportunities for collaboration and co-development. Opportunities to integrate Joint Force requirements, let alone ally and partner requirements, are not without additional challenges. Issues negatively affecting the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program are a prime example.

Utilizing the MCA pathway, the F-35 is the largest ongoing joint force acquisition program. Including three service components, eight international partners, and four additional nations with interest in procurement, the F-35 program has been in progress since the late 1990s. With costs estimated to exceed $406 billion, the F-35 program is still undergoing flight testing in order to resolve eight Category 1 deficiencies – “major flaws that impact safety or mission effectiveness.”, In addition to production delays, international partners have voiced concerns about the U.S. government and other contractors having accessibility to their respective flight operations data via the F-35’s Automatic Logistics Information System (ALIS). Foreign partners perceive the ALIS, the sustainment and maintenance system utilized by the entirety of the multinational F-35 fleet, to be a security risk because it currently sends partner flight data to the U.S. and program contractors.

The AAF provides process improvements for the acquisition of Joint Force requirements and getting assets to the warfighter faster than before, but all previous updates to the DAS fail to adequately incorporate ally and partner capability requirements or input. The MCA pathway currently presents the easiest, most expedient option for the Joint Force to strengthen partnerships and take advantage of opportunities with allies and coalition partners because of the size of the acquisition programs which utilize it. The other AAF acquisition pathways do not permit any ally or partner participation. While such exclusions may be appropriate in some circumstances, completely excluding allies and partners from these pathways constrains the Joint Force.

Ally and Partner Interoperability as a Capability Requirement

U.S. defense doctrine repeatedly extols the importance of interoperability. Interoperability is also one of the key facets of U.S. involvement in NATO, the largest military alliance in existence. Not only do NATO allies and other partners actively seek interoperability with the U.S. Joint Force, but the U.S. military itself codifies interoperability into the National Defense and Military Strategy vernaculars. While the intent for interoperability is clear, the follow-through leaves room for improvement. As noted, the MCA acquisition pathway considers interoperability, but allies and partners do not directly participate in the JCIDS process or any acquisition pathway. Without their direct involvement, the Joint Force does not give enough consideration to ally and partner interoperability requirements. The result is implementation of time-consuming, expensive follow-on acquisition programs, meant to solve interoperability problems between matured systems. The cycle of designing and then redesigning systems to meet interoperability requirements can be avoided by permitting allies and partners to participate in the JCIDS process, thereby giving their interoperability requirements more emphasis from the earliest stage possible.

Interoperability is defined by the Joint Force as “the ability to act together coherently, effectively, and efficiently to achieve tactical, operational, and strategic objectives.” NATO defines it “as the ability for Allies to act together coherently, effectively and efficiently to achieve tactical, operational, and strategic objectives.” A common theme emerges between the two definitions; they are identical except for the word “Allies.” U.S. military doctrine clearly had an influence on NATO’s concept of interoperability, but “despite broad consensus with policy establishments that interoperability is an important goal, there is a paucity of academic literature on it.” This scarcity is also evident at the earliest phases of capability requirement development.

When Combatant Commanders provide capability requirements to the Joint Requirements Oversight Council (JROC), the organization that manages the JCIDS process, the focus is generally on the short- and medium-term acquisition solution for capability gaps. Starting at the Theater Campaign-level after funneling up from tactical requirements, Combatant Commanders and their staffs compare Lines of Effort with available capabilities. Analysis reveals areas where particular missions cannot be executed considering current risk, so “any inability to execute a specified course of action is considered a capability gap.”

While Combatant Commanders look at more immediate capability gaps, the Services themselves tend to focus on long-term, strategic thinking focused on how to win the Nation’s future conflicts. The tension between the two timeframes has led to some of the aforementioned criticism of JCIDS, namely ignoring urgent capability requirements to instead focus on future conflicts. Interestingly, in an attempt to address these tensions a 2012 U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report to Congress on the major faults in the JCIDS process at the time does not mention the words “foreign” or “international” at all and only mentions “partner” twice. It does detail a facet of the JCIDS process pertaining to the “JROC-interest designation,” which is applied to “all joint doctrine, […] and programs and capabilities that have a potentially significant impact on interoperability in allied and coalition partner operations.” While the concept of allies and partners seems to be given some consideration in the report, minor deference is by no means significant enough to solve the problem.

Successive reviews and modifications to the JCIDS process have arguably alleviated some of the aforementioned tensions. Today, “JCIDS exists primarily to ensure that new DOD capabilities are needed, properly scoped, and fielded in a manner that is interoperable, resilient and supportable.” Joint Publication 1-0 also reiterates the importance of interoperability, instructing that “when JFCs organize their forces, they should also consider the degree of interoperability among Service components, with multinational forces and other potential participants.” Once again, interoperability with allies and partners is given consideration at the JFC level of capability requirements, but such consideration has not translated into results. As Richardson explains, “these efforts signal that the topic of interoperability is now a focus of high-level strategic planning, [yet] each lacks more specific discussion of how it is achieved.” Interoperability problems between the aforementioned F-35 and the earlier generation fighter aircraft flown by U.S. allies is an example.

The F-35 program is indicative of how a multinational approach to weapon system development could be executed, but that weapon system’s interoperability problems with older ally and partner aircraft and systems are ongoing. Richardson notes that “F-35s have been designed to cooperate with one another rather than with existing NATO fighter aircraft.” The aircraft can communicate and integrate with other F-35s, but incorporating it into NATO’s fourth generation fleet of fighters represents the next time-consuming, costly stage of the system’s development. At the operational level, NATO has been trying solve the fifth generation interoperability problem through the 2018 Joint Air Power Strategy (JAPS), but the Joint Force and its allies and partners will grapple with technical issues between the various generations of fighter aircraft for the foreseeable future.

Solving F-35 interoperability problems will continue, but it would be easier to design and field future weapon systems if interoperability with the legacy systems used by allies and partners is considered a capability requirement at the earliest stages of development. The indifference of the JCIDS process towards ally and partner interoperability is only going to present larger, more complex problems in the future as weapon systems transition to communicating more with each other than their users do.

The next evolution of military weapon systems incorporates advanced communication and sensory capabilities. The terms net-centric, synergy, and big data are commonplace. Yet the importance of such systems being able to communicate with each other and present data in a useable, efficient fashion is still not receiving the attention it needs at the earliest stage of development. As weapon systems grow more complex and more interconnected, the need for having allies and partners at the table earlier could pay dividends in the future. If this is not addressed, “programs where interoperability problems are discovered too late may suffer delays, cost overruns, or—worst of all—contribute to deadly mistakes at critical times.”

There have been positive developments regarding the roles of allies and partners in the JCIDS process. One of the most recent policy updates enacted by the JROC requires DOD organizations focused on international security cooperation to participate in the staffing of JCIDS requirements documents. Requiring DOD subject matter experts from these organizations to participate in the JCIDS process helps highlight ally and partner capability concerns. The JROC policy update gives the Joint Force’s strongest advocates for international security cooperation a seat at the table, but any input they provide is not coming directly from allies or partners. As Vice Admiral Bruce Lindsey recently noted when analyzing U.S. Navy interoperability with NATO allies, “creating active interoperability requires commitment to persistent engagement and careful coordination.” The next step to ensuring interoperability with allies and partners is to consider their interoperability requirements at the earliest stage of weapon system development – the capability requirements phase of the JCIDS process. Interoperability with allies and partners will continue to be an issue until such requirements are addressed.

Efficiency Gains through the JCIDS Process

Another consistent critique of the JCIDS process is directed at its slow speed and deference to unimaginative ideas. The process is complex, bureaucratic, and intimidating for contractors. Each step requires large amounts of funding, documentation, analysis, and approval to move forward. Even with the additional pathways provided by the AAF, the bureaucratic nature of the JCIDS process can be stifling to innovation. This is especially pronounced when addressing urgent priorities, but “in order to make the process more effective […], the DOD will need to sacrifice control for speed by allowing […] innovative solutions and to more rapidly acquire new, cutting-edge technologies […] and get them in the hands of the warfighter.” Allowing foreign allies and partners to participate in the JCIDS process gives the Services a potential solution, but not without risk. The bureaucratic nature of JCIDS is deliberate.

Major acquisition programs such as the F-35 have budgets well into the hundreds of billions of dollars. Although there have been attempts to accelerate the overall acquisition process of that program, large programs generally go through constant reviews to ensure accountability at each step. In concept, the bureaucratic nature of constant oversight prevents stove pipes and service parochialism while ensuring Joint Force interoperability and that the most needed capabilities are achieved.

As discussed previously, the MCA pathway for major acquisitions provides an opportunity to collaborate with allies and partners. Major acquisition programs also require long-term commitment between the U.S. and its allies and partners, an objective of the NDS. “International collaboration through acquisition programs helps forge trust and achieve force-multiplier synergies as strategic plans evolve that depends on access granted by our global partners.” Early engagement in the acquisitions process is also vital: aside from giving consideration to interoperability, it also can provide distinct economic and resource allocation benefits. “In the current budget-challenged environment, there is no better time for both warfighters and acquisition planners to proactively assess and factor partner-nation capability requirements into our domestic requirements, budgeting, and acquisition planning.”

Commonality amongst various pieces of defense equipment allows for economies of scale both during development and throughout the equipment’s lifespan. Involving foreign partners also helps strengthen U.S. influence and interests during acquisitions collaboration. While collaboration presents opportunities, it can also increase complexity and create other distinct challenges. The Eurofighter program, originally a consortium of five nations, helps illustrate some of those challenges.

At its outset, the Future European Fighter program was a collaborative effort between the U.K., Germany, France, Italy, and Spain. While initial requirements were gathered, disagreements about specific baseline capabilities, oversight of the program, and industrial basing led to France leaving the effort and establishing its own program. As the program continued to develop, operational roles, mission priorities, required capabilities, and program funding differences all created friction. “Under the original consortium arrangements, upgrades were supposed to be jointly funded and developed. This has proved a predominantly unworkable model given the significantly different operational imperatives and doctrinal role for the Eurofighter in British, German, Italian and Spanish service.”

Spreading the economic burden of development, as well as capturing the economic advantages of shared production, seems to favor programs like the Eurofighter consortium. With each country purchasing the same (or similar) aircraft, the economy of scale advantages increase, driving down the cost of the end items, as well as a distributed industrial base to provide sustainment over the life of the airframe. Dividing the economic burdens of the development, vice going in alone, also made the program more appealing. Both of those goals never fully came to fruition for the Eurofighter, with the costs of the program continuing to increase. “As the main reason for collaborating on a major defence project is reducing its cost – R&D costs are divided among the participating partners […] – value for money must be considered one of the main criteria of success. However, the Eurofighter programme has been accused of mismanagement and inefficiency and has suffered cost overruns running into billions.”

Considering the challenges of programs like the Eurofighter provides an opportunity to shape future multinational collaborative acquisition programs that could originate from the JCIDS process. Oversight by committee is always challenging. Acknowledging potential points of friction with stakeholders early, however, helps set expectations. Yet the requirement to have oversight and addressing points of friction early ties directly to the long-term commitment required for successful defense acquisition program collaboration. The Joint Force must select partners that are dedicated to a lasting partnership with mutual goals. The collaborative effort must produce on the value proposition of shared costs and common requirements. One program where there should be very little divergence in capability requirements between the Joint Force and allies and partners is the development of a jet trainer aircraft for future fifth-generation fighter pilots.

In 2009 the U.S. Air Force showed that 12 of 18 future mission tasks could not be accomplished in its aging T-38C jet pilot trainer. The JROC subsequently approved a Capabilities Development Document (CDD) requiring a material solution. The 12 future mission tasks that the T-38C could not facilitate were heavily focused on preparing pilots to successfully operate fifth generation fighter aircraft. Interestingly, the majority of the companies who had bid to win the contract to build the T-X were partnerships between major American aerospace defense companies coupled with foreign equivalents such as Italy’s Leonardo, the Republic of Korea’s Korean Aerospace Industries (KAI), Great Britain’s BAE, Canada’s CAE, and Turkey’s TAI. While all of the aforementioned countries planned to incorporate five fifth-generation F-35s into their armed forces, none of their respective militaries participated in the capability requirements phase of the weapon system. This is a missed opportunity.

On 27 September 2018, U.S. Air Force selected the proposal from a joint Boeing/Saab venture to create a “purpose-built trainer […] designed from the ground up” to meet capability requirements to train future pilots of fifth-generation aircraft. As the U.S. Air Force moves forward towards creating the next generation jet fighter trainer, allies and partners have no involvement. Their absence from the program not only presents both future interoperability problems, it also fails to spread out the cost of weapon-system development among a group of participants that have the same capability requirements for fifth-generation fighter aircraft pilot training.

The current directives and organization of the JCIDS process do not permit allies and partners to actively participate in the JCIDS process. Permitting ally and partner direct involvement in the JCIDS process supports achieving NDS requirements by establishing trust through participating in advanced, long-term acquisition programs, facilitating future weapon system interoperability requirements, and taking advantage of design and cost efficiencies through economies of scale. If the JCIDS process is to continue being the Joint Force’s starting point for building future capabilities, incorporating agility into the process to allow allies and partners helps achieve shared capability requirements as well as U.S. NDS objectives. The JCIDS process should not mandate that allies and partners participate on every project or acquisition pathway, but there needs to be an opportunity. Modification to the JCIDS process to allow ally and partner participation is a way for the U.S. and the Joint Force to fulfill the Secretary’s guidance in the NDS. Ignoring the current gap will only add inefficiencies, cost, and risk in the future.

About the Authors

Lieutenant Colonel Shoupe is a Senior Pilot and FAO serving as the U.S. Air Attaché to Uzbekistan.

Lieutenant Commander Suárez is currently serving as a Joint Logistics Planner at U.S. Special Operations Command South.

Major Yurkovich is currently serving as a Joint Working Group Lead on the Joint Staff, J35.