RECALIBRATING INTERNATIONAL PEACE AND SECURITY EFFORTS IN THE SAHEL

By Group Captain Mohammed Bello Umar, Nigerian Air Force,

Editor's Note: Group Captain Umar's thesis won the FAO Association writing award at the U.S. Air War College. Because of thesis length we publish here a condensed version. To see he full thesis with all research materials, please visit www.faoa.org or email editor@faoa.org. The Journal is pleased to bring you this outstanding scholarship.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. government, the Department of Defense, or Air University. In accordance with Air Force Instruction 51-303, it is not copyrighted, but is the property of the United States government.

Introduction

The Sahel is a region in crisis because it presents the international community with serious challenges ranging from violent extremism, communal tensions, weak institutions, and increasing displacement of the populace, to name a few. The crisis in the region is further exacerbated by climate change resulting in external intervention to help stabilize the region. In 2012, Malian Tuareg groups previously serving as private armies in Gaddafi's Libya returned to Mali, triggering a rebellion that led to a military overthrow of the Malian government at Bamako, the capital. An overwhelming international consensus to intervene arose when the Malian government could not halt the insurrection. Subsequently, at the request of the Malian state, France, assisted by the Chadian troops from the African-led International Support Mission to Mali (AFISMA), intervened under Operation Serval, recapturing areas under insurgent control. French Operation Serval was rehatted to Operation Barkhane while AFISMA morphed into the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). Although the international military intervention succeeded in ejecting the insurgents from significant towns and urban areas, its control never extended to the rural areas.

The violence that began in Mali has since 2016 spread across the region, with the Sahel becoming a hub for transnational violent extremist organizations (VEOs) and conduits for drugs, human and weapon trafficking, further destabilizing the region. Countries in the region have seen varying degrees of regional and external intervention to help address the deteriorating security situation. However, despite the multitude of responses, security in the Sahel has worsened with armed violence spilling into the central region of Mali and neighboring countries such as Burkina Faso and Niger. This violence has led to the displacement of 2.7 million persons across the region, with at least 13.4 million in dire need of humanitarian assistance.

The present rise in violence attributed to the expansion of VEOs, counter mobilization of self-defense groups, and ensuing inter-communal violence pushes Sahelian states to the brink of collapse. Three extremist groups account for most of these attacks, and these are the Jama'at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), which is Al-Qaeda's associate in Mali, Macina Liberation Front (FLM) with ties to JNIM, and the Islamic Group for the Greater Sahara (ISGS). International interventions risk causing further damage by focusing only on counterterrorism and poorly thought-out development initiatives that focus on states' collapse and contagion instead of addressing the more profound governance challenges. Accordingly, even though security approaches will stabilize the Sahel in the short term, to ensure sustainable stabilization of the region, this paper argues that a coordinated strategy promoting human security, an expanded peace process to deescalate violence, and political dialogue on a state role for Islam that delegitimizes Jihadist appeal will stabilize the Central Sahel.

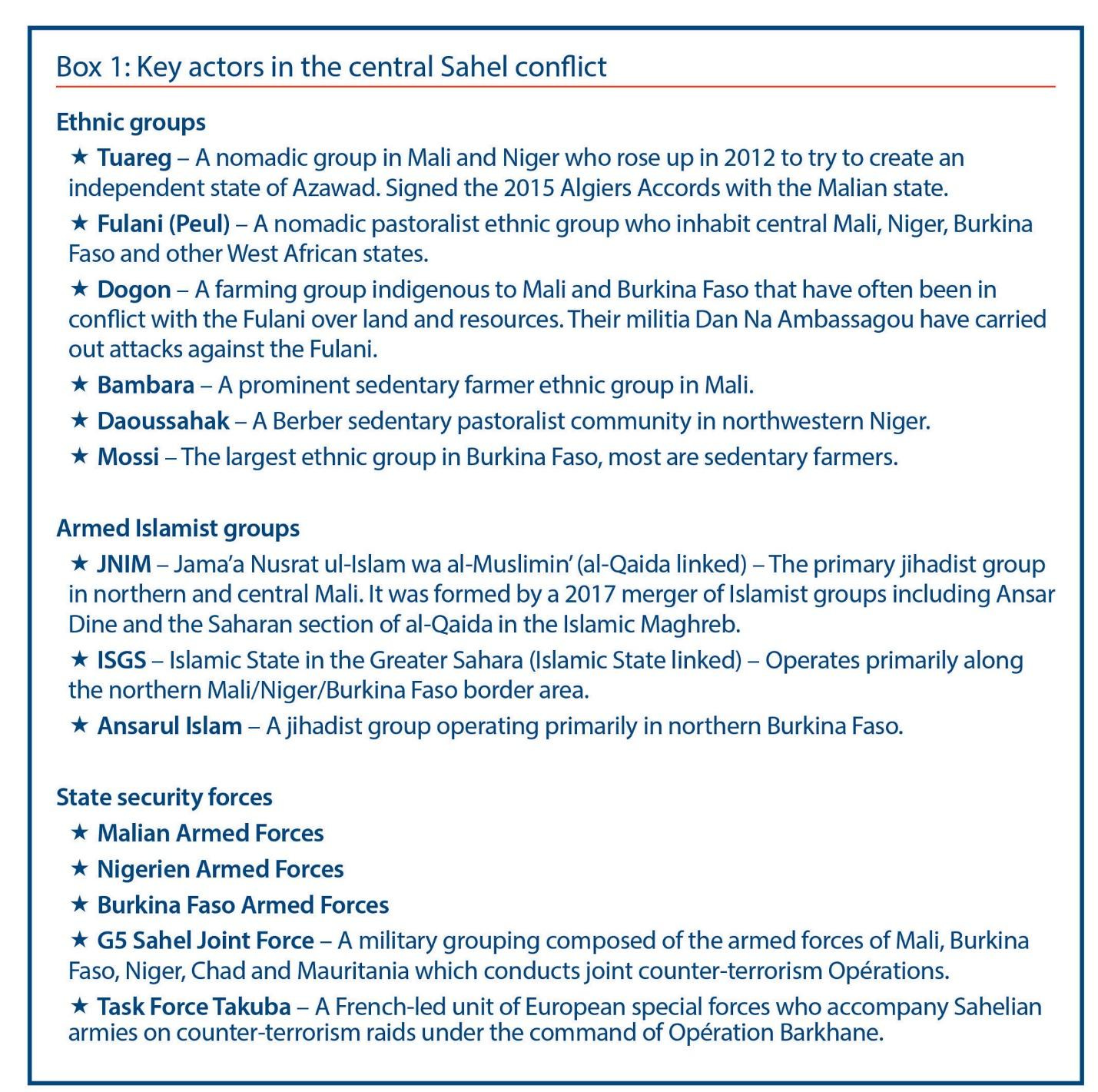

This paper will offer a broad overview of the current conflict environment in the Sahel, paying attention to the region's intersecting and overlapping security issues. Next, the paper will explore the role of regional and international actors. It will interrogate how the participation of various actors impact stabilization in the Sahel, especially as various actors focus on their interest. For example, the European Union is concerned with migration from the Sahel to Europe; the U.S. is interested in fighting terrorist groups; France defends its overall strategic and economic interests in the region. The subsequent section will examine some challenges and gaps concerning the existing international framework. This section will explore how the lack of a strategic vision among actors, the militarization of stabilization, and the Sahelian states' fragile nature impact international efforts. Finally, suggestions on alternative policy responses that deemphasize military responses will be made for both regional and international actors. The Sahel extends from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea and incorporates parts of Senegal, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Algeria, Niger, Chad, Sudan, and Somalia. Considering the expanse of the Sahel, this paper will focus on the central Sahelian states of Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mauritania. Figure 1 shows the disposition of the VEOs in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, while Table 1 outlines the key actors in the conflict.

Figure 1. Map showing VEOs in the Central Sahel (Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger)

Source: Africa Center for Strategic Studies. "Surge in Militant Islamist Violence in the Sahel Dominates Africa's Fight against Extremists," January 24, 2022. https://africacenter.org/spotlight/mig2022-01-surge-militant-islamist-violence-sahel-dominates-africa-fight-extremists/.

Thesis

International interventions in the Sahel region risk causing further damage by focusing only on counterterrorism and poorly thought-out development initiatives that focus on states' collapse instead of addressing the more profound governance challenges. Accordingly, even though security approaches will stabilize the Sahel in the short term, to ensure sustainable stabilization of the region, this paper argues that a coordinated strategy promoting human security, an expanded peace process to reduce violence, and political dialogue on a state role for Islam will delegitimize Jihadist appeal and stop the region from devolving into further violence.

Table 1: Key Non-State and State Actors in the Sahel Conflict

Source: Catherine Pye, "The Sahel: Europe's Forever War?" Centre for European Reform accessed February 27, 2022, https://www.cer.org.uk/publications/archive/policy-brief/2021/sahel-europes-forever-war.

Conclusion

As the Sahelian conflict approaches its first decade, the international community needs to readjust the military first approach towards stabilization to avert deteriorating humanitarian and security challenges. A new strategy emphasizing negotiations between regional states and VEOs, a cohesive effort towards human security, and broad consultations on a representative role for Islam in national affairs will help stabilize the region. Although secessionist Tuareg rebels first incited the Sahelian crisis, it has spread to include competing groups with assorted objectives thriving in an ecosystem of dysfunctional and deficient statehood. The multiplicity of state and non-state actors in the region's conflict ecosystem has resulted in social, economic, and humanitarian consequences, with communities being the victims of terrorist attacks.

Violent non-state actors such as the JNIM and Macina Liberation Front, even though perceived by the international community as an existential threat, provide reliable channels for resolving local grievances and conflicts in territories where the state cannot maintain a competent and qualified presence. In a situation where no contender can enforce a more extensive political order, it is hard to envision a political solution to the Sahel crises without involving other non-state actors in state-approved stabilization and conflict management processes.

The regional and international counterterrorism strategy for the Sahel fragments humanitarian space due to its narrow focus on VEOs and migration control. These divisions necessitate a more coordinated and collaborative approach to human security from UN peacekeeping, counterterrorism, and development agencies. The international community needs to unravel its many security activities with overlapping jurisdictions and aims. To carry out their counterinsurgency, peacekeeping, and border security missions, Sahelian and European countries and institutions like the UN, AU, G5 Sahel and ECOWAS need to create a more collaborative concept of operations.

Islam has a lengthy history in the Sahel, and the current insurgency has heightened the discussion about Islam's place in society and politics. A public debate on Islam's role would be delicate and challenging. Nevertheless, it will help contest sacred space with violent extremist groups allowing possible concessions and conciliation between the government and the groups' leadership. Such dialogues may undermine the secularity of Sahelian states. However, the rejection of Islam as a source of legal or administrative principles for the willing section of the populace undermines the state's legitimacy and instead reinforces violent extremists' narratives.

To this end, it is challenging to predict a viable strategy to stabilize the Sahel within existing political institutions and authority norms. Additionally, any proposed approach may not quickly halt the spiraling humanitarian catastrophe or restore Sahelian states capacities. The future of the Sahel must be crafted through the understanding of religious, ethnic, and commercial interconnections woven into the fabric of the region's history. The current interventions need to factor in that history to stabilize the region successfully. Therefore, a revised and inclusive political pact with citizenry and all segments of society, even though imperfect, might legitimize regional states and prevent the further escalation of the conflict into West Africa and Europe.

About the Author

Group Captain Mohammed Bello Umar is a Nigerian Air Force attack helicopter pilot. Prior to attending the U.S. Air War College he commanded the 405 Helicopter Combat Training Group, Enugu, Nigeria. Group Captain Umar was commissioned to the rank of Pilot Officer after his officer cadet training at the Nigerian Defense Academy, Kaduna, in 2002. Group Captain Umar has attended several flying courses and is an instructor pilot. He had participated in several internal security operations across Nigeria and engaged in regional counterterrorism operations under the auspices of the Lake Chad Basin Multinational Joint Task Force against Boko Haram. He has served at the Wing, Group, and Headquarters levels of the Nigerian Armed Forces. He holds a bachelor's degree in Electrical Electronics Engineering and a master's degree in Military Studies. Group Captain Umar had also commanded several units in the past.