Editor's Note: This thesis won the FAO Association writing award at the Joint and Combined Warfighting School, Joint Forces Staff College. The Journal is pleased to bring you this outstanding scholarship.

Disclaimer: The contents of this submission reflect our writing team’s original views and are not necessarily endorsed by the Joint Forces Staff College or the Department of Defense.

By Captain Jason Burns, U.S. Navy;

Lieutenant Colonel Keith L. Carter, U.S. Army;

Lieutenant Colonel Amanda Figueroa, U.S. Air Force;

Colonel Chris Holloway, U.S. Marine Corps; and

Lieutenant Colonel Parker Stewart, U.S. Air Force

I

The recent U.S. strategic emphasis on great power competition below the level of war resident in the 2017 National Security Strategy and the 2018 National Defense Strategy has oriented the national defense apparatus to the challenge, but what does this shift imply for the traditional military understanding of “success?” In this context competition is a continuous, iterative process that takes place around the globe, in space, and in cyberspace that will require coordination across the whole of government to succeed. Importantly, as China and Russia grow in strength, the influence they wield will change the structure of the international system. From a realist perspective, in an international environment defined by anarchy and where the intentions of other states cannot be truly known, states must attend to their own security by amassing power. Tragically though, the act of gaining power, even if belied by benign intention, causes others to attend to their own security by increasing their power—trapping the participants in the spiral of the security dilemma and ironically increasing the chance of war. The stark logic of the security dilemma manifests itself most in an international system of multipolarity. Multipolar systems are the least stable, and the most likely to lead to war. In other words, a multipolar world is likely to be fraught with security challenges, and, as the power of China and Russia grows and the international system returns to multipolarity, the U.S. must be ready to compete with other states to maintain its economic, social and security advantages.

What impacts will shifting to a strategy oriented on Great Power Competition and engaging in competition below the level of war have on the traditional military understanding of “success?” Competition is the interaction among actors in pursuit of the influence, leverage, and advantage necessary to secure their respective interests. Success in competition is measured as an ongoing evaluation of one’s freedom of action relative to competitors, a dynamic challenge that constantly evolves with geopolitical and technological developments. America possesses the most expensive and well-trained military in the world. However, the National Security Strategy clearly states that conflict and hostilities are not a required biproduct of competition and that “[a]n America that successfully competes is the best way to prevent conflict.”

As the international environment returns to a state where powerful regional actors such as China, Russia, and Iran are successfully vying to increase their position vis-à-vis the United States, it is important to rethink the features of great power competition. To compete successfully in this ever-evolving environment, we must divorce ourselves from the simplistic and binary terms of winning and losing, or war and peace. Competition below the level of war and the expansion of the “competitive mindset” requires a more diverse lexicon to translate strategic direction into operational reality. This paper starts by examining some of the bias in current doctrine that prevents the effective conceptualization of competition below the level of war. It introduces the concepts of desired futures, sustainable outcomes, and the competitive fulcrum to use in modeling and planning for competition. Next, it examines how these concepts manifested in historical examples of competition below the level of war. Finally, it discusses the utility of these concepts in measuring success.

II

In his book Destined for War, National Security scholar Graham Allison analyzed 16 historical vignettes describing competitive tensions between established and rising powers. Allison’s analysis showed four instances where the competitive tensions between great powers were managed and resolved without war, demonstrating that, in spite of the difficulties, it is possible to compete without necessarily engaging in large-scale violence. Due to the widespread deleterious effects of war, the goal of national security professionals should be to compete effectively without assuming conflict is the desired or de facto outcome. This does not imply that the national security apparatus will avoid conflict since adversary actions may necessitate it, or national policy makers may ultimately direct it. But the doctrine of military strategy, as currently written, does not support thinking about or planning for competition below the level of war. Instead, it is written to teach and train military forces to secure victory in as short and efficient a manner as possible, focusing conceptually on the “endstate”, “termination criteria”, and “centers of gravity” -- all of which assume some period of time elapses until military objectives have been achieved and the situation is concluded. Current doctrinal terms also fail when grafted into non-conflict scenarios requiring the application of military power, or in continuous competitions where the goal is rarely achieved by military power alone.

Military planning models such as the Joint Planning Process (JPP) outlined in Joint Publication 5.0 are useful in designing classic military operations targeting enemy centers of gravity. A center of gravity is a “source of power that provides moral or physical strength, freedom of action, or will to act”, and the objectives of well-planned military action should always be tied back to an adversary’s center of gravity. Identifying enemy centers of gravity is an important part of operational design and can include analyzing an adversary’s “military force, an alliance, political or military leaders, a set of critical capabilities or functions, or national will”. Once identified, centers of gravity are pursued through operations which are frequently divided into phases, “distinct in time, space, and/or purpose from one another”. Such time-phased activities assist in developing an order of battle, or friendly force composition, which is meant to defeat an adversary’s centers of gravity through force until the termination criteria is met. Military efforts are meant to be aligned toward an end state, or “the set of required conditions that defines achievement of the commander’s objectives”. But linear arranging of military activities to achieve an end state is less useful in achieving success in a sustained campaign that doesn’t rely on violence as its primary mechanism.

This problem is articulated in a report by the Joint Special Operations University:

Joint Publication 5-0 clearly states it is just a guide, but the reality in practice…is that U.S. military culture, training, and experience have ingrained a desire and belief in controlling variables to affect the Center of Gravity. It leads to the attitude, ‘If I plan artfully enough, I can achieve my desired end state as precisely as I’ve envisioned it.’ This is fraught with danger because it encourages a war of ‘chasing the Measures of Effectiveness’ to prove a concept with an intrinsically short-term perspective and, very often, one that is not a reflection of local reality but of American cultural paradigms.

In other words, the lexicon used to describe the process ends up defining how the actor thinks about the inputs and outputs of the process. Limiting lexicon to terms suitable only for conflict prevents full or creative utilization of the military instrument of national power. Arguably, as the size of the Department of Defense (and its budget) increased in relation to other U.S. national institutions, the military manner of planning, speaking and thinking has migrated across the government and therefore impacts all the instruments of national power. While the traditional lexicon is valid for operations in conflict scenarios, in competitive scenarios the U.S. national security apparatus should shift from an end-state focused lexicon to a set of descriptive concepts which support sustained competitive interactions over time.

In addition to the traditional guidance of deterring and defeating threats to the U.S., the 2018 NDS instructs combatant commanders to execute campaigns to compete with great power challengers below the level of armed conflict. Competition, as the backbone of such a campaign, is “continuous and without the finite and clear end states that often characterize military plans”. Without a pre-determined conclusion to a campaign, the notion of end states results in cognitive dissonance and bias in the planner’s mind. Competitive activities do not necessarily conclude, but instead expand and adjust over time according to policy evolutions and competitor activity. For this reason, “backwards planning”, a common technique, must be reconsidered as the preeminent method of planning. Rather than achieving finite end states, a campaign of competition (and ideally cooperation) will be measured by sustainable outcomes, or the “realization of policy’s aims.” The importance of sustainability cannot be overemphasized. Successful efforts “rarely mean the end of the overall competition and few gains are reliably permanent.”

When combined together, groupings of sustainable outcomes in competition will lead toward the desired future set by policy. This is “the optimal trajectory toward which to strive within a range of possible futures.” Because competitive and cooperative activities occur in an open system of variables, the range of possible futures expands over time. Additional inputs and activities should always be oriented on the desired future. While it may be tempting to settle for a short term “victory” to satisfy immediate political desires, great consideration must be made that finite objectives do not compromise the long-term goals, with a mind “to increase options, not eliminate them.”

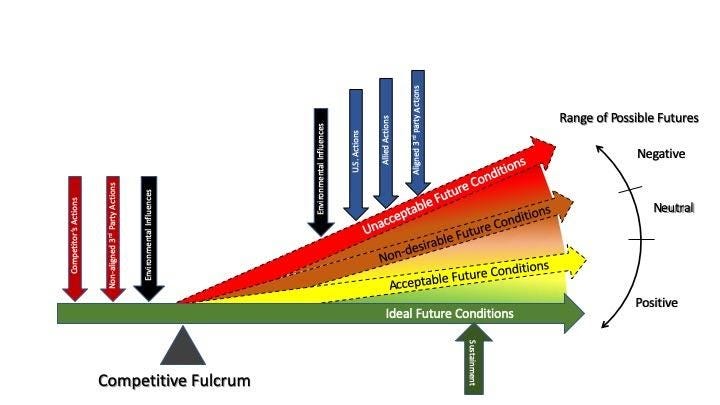

Figure 1. The Competitive Fulcrum (graphic by author)

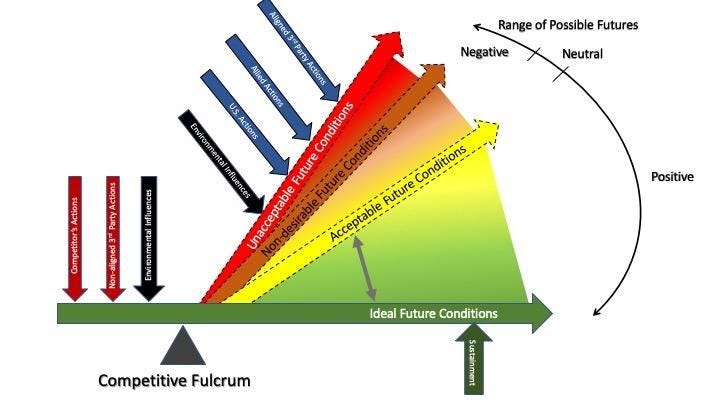

Once “end state” is replaced with a description of the desired future and associated sustainable outcomes, the concept of a “competitive fulcrum” can be used in place of “centers of gravity” or “targets”. A fulcrum is the point around which a lever (the future) pivots, depending on the forces applied. (See Figure 1). Competition also involves adversaries applying forces in opposition to our own, and third parties applying complimentary or counter forces as best suits their own interests. To make the situation more complex, competitors sometimes cooperate when it is in their interest to do so, at which point their forces may be aligned with our own to pivot the future around the competitive fulcrum. Successful competition and cooperation not only help further the desired policy aims, but also increase freedom of maneuver within the competitive area by adding options for policy-makers (e.g. additional levers, additional partners or expanded access). Successful competition is visualized by showing a greater area of ideal-acceptable future conditions, and therefore a longer positive segment on the arc of possible futures (Figure 2), while unsuccessful competition narrows options, decreases freedom of maneuver, and shortens the positive length of possible future outcomes. Conflict or capitulation becomes likely when either competitors’ range of acceptable possible futures is eliminated or becomes too narrow to be achieved using affordable or available means.

III

While this paper argues to adjust current U.S. doctrine to include expanded competitive concepts, competition itself has long been a staple of nation-state security. Within the context of history, one can discern the concepts of “sustainable outcomes”, “desired futures" and the hypothetical and analytical competitive fulcrum in past great power competitions. A modern accepted academic definition defines major or great powers, “explicitly or implicitly in terms of one or a combination of three dimensions: (1) power capabilities; (2) spatial aspect (geographic scope of interests or projected power); and (3) status (an acknowledgement of major power status, which should also indicate the nation’s willingness to act as a major power).“ Although many great power competitions throughout recorded history lend themselves to these definitions, this paper focuses on the Peloponnesian War, the post-World War I/pre-World War II interregnum of 1922-1936 (The Five Power, London Naval, and the Second London Naval Treaties), and the Cold War.

Figure 2. Successful Competition Expands Positive Futures (graphic by the authors)

The term “great power” originated during the post-Napoleonic Era corresponding with the establishment of the Concert of Europe, which described the balance of power between European nations beginning in 1815. Although several significant great power competitions took place after 1815, one of the most compelling occurred before the commonly accepted notion of great power between the city-states Athens and Sparta. This competition ultimately resulted in the Peloponnesian War, but the pretext for, and competitive efforts prior to, hostilities are illustrative of what great power competition looks like below the level of armed conflict.

Athens and Sparta: The First Competition Between Great Powers. In 480 BC, at the completion of the wars against Persia, Athens established itself as a great power, dominating the ionic peninsula, Aegean and northern Mediterranean Seas. Although aware of a perceived challenge to its hegemony by a rising competitor, Sparta, there was no great desire on the part of Athens to go to war with its challenger. Athens’ desired future was to continue her hegemonic dominance of the region and preserve unipolarity. In order to meet this goal, Athens’ chosen sustainable outcomes were to establish and maintain alliances with trading partners and friendly nations while competing directly politically and economically with Sparta. Sparta, as a developing nation and rising power, was initially satisfied with the status quo “near peer” competition below the level of armed conflict.

Applying the concept of a competitive fulcrum, both nations attempted to compete below the level of war, although Athens as the established power had more levers to apply. First, Athens attempted to align allies under an international organization known as the Delian League, to which other “client” states would pay tribute. It also attempted to export its brand of democracy abroad while simultaneously applying realpolitik to attempt to discredit other like governments, such as Syracuse. In fact, “Atheniansim” is considered to be the Western world’s first example of globalization.”

The large tributes paid by client states supported Athens’ world class “Fleet In Being” which controlled strategic waterways, and thereby trade, and provided Athens the ability to project power. Additionally, both nation states conducted proxy wars through their allies and partner nations. It is important to point out that although this is an evaluation of great power competition below the level of war, it is assumed that proxy war is a valid lever great powers use to obtain or sustain position and relative dominance. Sparta, as its stature grew, feared the growth of Athens and the export of Athenian-style democracy. It actively competed and challenged Athens everywhere that opportunity presented itself, going so far as attempting to prevent the rebuilding of the wall surrounding Athens that had been destroyed in the conflict with Persia. Sparta’s efforts were unsuccessful, but further fueled resentment and fear of Athens as a great power.

Ultimately, the competition below the level of war did not satisfy the competing powers. Athens’ and Sparta’s great power competition ultimately ended in war because neither side could utilize the levers of competition to keep the future within an acceptable range of possibilities.

Washington/London Naval Treaties. The great power competition described by the Washington and London Naval treaties resulted in a state of competition between major conflicts, but national desired futures, sustainable outcomes, and the competitive fulcrum concepts still apply. In the aftermath of World War I, there was a movement towards world government (the League of Nations) and the elimination of future war and violent confrontation. This effort supported President Wilson’s desired future of lasting peace and elimination of armed conflict through the direction and management of a world government.

Towards this end, in an attempt to establish a sustainable outcome, there was a movement to limit worldwide armaments and associated arms races. The first treaty, also known as the “Five Power Treaty” was signed in 1922. The treaty was designed to limit both numbers and maximum tonnage of several classes of warships (battleships, battlecruisers, and aircraft carriers) and eliminate a naval arms race between the great and rising powers of the time.

At the completion of World War I, the defeat of Germany left the United Kingdom’s Royal Navy as the preeminent fleet. Immediately following the cessation of hostilities, the rising powers (United States, Japan, Italy, France) planned to significantly expand their fleets to reach naval parity with Britain. Given the vast devastation and loss of life from World War I, there was little political appetite in either the United States or Great Britain for an arms race. The treaty stipulated a ratio of 5:5:3:1.75:1.75 for capital ships, where the single digit reflected 100,000 tons (i.e. “3” was 300,000). The treaty assigned “5” for the U.S. and U.K., “3” for Japan and “1.75” for France and Italy.

The treaty ultimately was the predominant lever in an attempt to level the competitive fulcrum during the interwar period. Although all five nations signed the treaty, the failure of the League of Nations prevented enforcement and cheating was rampant by the second Washington treaty. Germany had already begun to re-arm in secret. Japan, the other rising power and direct competitor to the United States, used the treaty to hold the industrial advantage of the U.S. in check. Arguably, the treaty compelled Japan to pursue competition through other means, leading the Japanese military to pursue a policy of preemption to meet its own desired outcome in the Pacific. This policy and “(leadership) purges set the stage for Japan’s universal abrogation of the Washington Treaty in 1935 and withdrawal from the Second London Conference of 1936, signaling resumption and escalation of the naval race – which naval historians have felicitously called ‘the race to Pearl Harbor.’”

Much like the great power competition between Athens and Sparta, the inter war period characterized by the London and Washington Naval treaties ultimately led to war. The United States and United Kingdom, although acting towards realization of both nations’ desired futures and sustainable outcomes, ultimately were unable to maintain a range of acceptable futures using treaties and world government organizations as levers against the levers associated with German, Italian and Japanese nationalism.

The Cold War.

After completion of World War II, the global balance of power shifted from historically colonial powers (United Kingdom, France, Germany) to the United States and the Soviet Union (USSR). This, and the advent of nuclear weapons, redefined great power competition, creating the ultimate competition below the level of war: the Cold War.

For the United States, who emerged from World War II as an established great power, the desired future was, much like Wilson’s view after World War I, a world regulated by a world government (the United Nations) and guided by the United States’ strategic and foreign policy goals and desires. The Soviet Union perceived this as an existential threat and established its desired future as national survival and global strategic relevance, painting the U.S. and capitalism as its chief rivals. As the Cold War progressed and the Soviet Union became a nuclear power, the agreed upon strategy for the use of nuclear weapons between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. became mutually assured destruction. The primary focus of this strategy was deterrence, and the result of a policy failure was nuclear Armageddon. Because of the obvious finality of nuclear war and destruction of both nations, the U.S. and U.S.S.R. sought to avoid great power armed conflict and instead competed globally, below the level of war, to bring about their desired future.

To challenge the expansion of communism in the Soviet Bloc and from satellite nations such as North Vietnam and Cuba, the United States decided on the strategy of Containment. Envisioned by George Kennan, Containment was first articulated in 1946 in a cable from Kennan to George Marshall and then published in Foreign Affairs magazine in 1947 under a pseudonym. Containment became the primary sustainable outcome with regard to the Soviet Union since it enabled a broad range of options for competitive action outside of Soviet held territory. As a strategy, Containment was designed to challenge the Soviet Union economically, spiritually, and philosophically, limiting their influence. Kennan described the challenge of competing with the Soviets in this way: “my conviction that the problem is within our power to solve-and that without recourse to any military conflict,” literally defining competition below the level of war.

The U.S. and U.S.S.R. pursued their rivalry through various means below the level of armed conflict, including treaties (NATO, Warsaw Pact), proxy wars (Vietnam, Iran/Iraq War, Six Day War, Afghanistan), economic aid, and use of military forces without resorting to combat operations. According to Stephen S. Kaplan in Force Without War: The United States’ Use of the Armed Forces as a Political Instrument, the U.S. used armed forces as a discrete political instrument 226 times from 1 January 1946 to 31 December 1976. Kaplan stated “[a] political use of the armed forces occurs when physical actions are taken by one or more components of the uniformed military services as part of a deliberate attempt by the national authorities to influence, or be prepared to influence, specific behavior of individuals in another nation without engaging in a continuing contest of violence.” The presence of military forces was often used as the primary lever to balance the competitive fulcrum, whether it was land forces in Korea and West Germany, naval deployments to the Mediterranean and Arabian Gulf, or in events such as Multi-National Force in Lebanon and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Ultimately, the U.S. successfully competed below the level of war by leveraging containment via the political use of armed forces, the opening of China, and the pressure of the arms race required to counter U.S. military strength to drive the economic and political demise of the U.S.S.R. Once the use of strategic nuclear weapons was removed as an option via the MAD doctrine, over time, the U.S.S.R.’s spectrum of possible futures continuously narrowed until the only positive option was capitulation. On the other hand, failure of Containment would have continuously and iteratively limited the U.S.’s options for action, reducing the acceptable portion of the arc of potential futures.

IV

Success in competition below the level of war is extremely hard to measure. For example, consider the restriction of tonnages during the inter-war period. In this case, an easily quantifiable measure (tonnage) was perceived to exert substantial pressure on the competitive fulcrum towards creating a desired future where a naval arms race was avoided and the U.S. and the U.K. could retain naval superiority. To Japan however, this competitive solution was suffocating and humiliating, thus this lever exerted minimal effect towards the desired future and ultimately furthered Japan’s imperial ambition. U.S. bureaucracy and budgeting runs on reinforcing successful programs that can provide data to illustrate they are achieving their stated goals, and stepping away from the “war of chasing Measures of Effectiveness” leaves no easy method for measuring if the actions taken are appropriate to succeed in competition. Selecting the right levers and understanding their effectiveness toward creating a desired future without the benefit of historical hindsight is a monumental analytical task that will require a shrewd understanding of the strategic environment. When it goes well—like it did during the Cold War when the U.S. leveraged economic competition with the Soviet Union toward a desired future of containment—it allows pursuit of national interest below the level of war.

While the underlying logic of the competitive fulcrum, as supported by sustainable outcomes and desired futures cannot be measured in hard numbers, it can be leveraged as a visualization tool that incorporates qualitative judgements on the expansion or contraction of the range of positive possible futures. It can depict whether the U.S. has more options for maneuver or less, and whether other states are acting cooperatively or competitively. Ultimately, it can serve as a tool to broaden our vocabulary which will help keep planners and decision-makers focused on the continuous nature of competition and prevent myopia or fixation on single events, theaters or outcomes that become detrimental to long-term sustainable outcomes.

About the Authors

Captain Burns is Commodore, Amphibious Squadron Five. He was commissioned through NROTC at San Diego State University in 1993. CAPT Burns earned a BA in Political Science from San Diego State University in 1993 and a MA in International Relations and Strategic Studies from the Naval War College in 2007. Prior to his current assignment, CAPT Burns served as Commanding Officer, USS Essex (LHD 2).

Lieutenant Colonel Carter is a strategic planner in the Joint Special Operations Command. He was commissioned through the University of Montana in 2000. LTC Carter earned a BA in Philosophy from the University of Montana in 2000, a MS in Defense Analysis from The Naval Postgraduate School in 2012, and is ABD in Political Science from the University of Pennsylvania. Prior to his current assignment, LTC Carter served as the Battalion Commander of 1st Battalion 26th Infantry Regiment at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

Lieutenant Colonel Figueroa is a Fellow to the Director of the National Security Agency. She was commissioned through ROTC at the University of Wisconsin in 2001. Lt Col Figueroa earned a BS in International Relations from the University of Wisconsin in 2001 and a MA in Diplomacy and International Conflict Management from Norwich University in 2007. Prior to her current assignment, Lt Col Figueroa served as the Commander of the 30th Intelligence Squadron, Langley Air Force Base, Virginia.

Colonel Holloway is the Assistant Chief of Staff G-1, I Marine Expeditionary Force. He enlisted in the USMC in 1985. He was commissioned through the Officer Candidate Course in 1996. COL Holloway earned a BA in Graphic Design from the University of South Carolina in 1995. Prior to his current assignment, Col Holloway served as the Executive Officer, 8th Marine Corps Recruiting District.

Lieutenant Colonel Parker is Action Officer for the Deputy Director of Special Operations, Counter Terrorism and Detainee Affairs on the Joint Staff. He was commissioned through the Air Force Academy in 2002. Lt Col Parker earned a BS in Humanities 2002 and a MA in Military Operational Art and Science from Air Command and Staff College in 2015. Prior to his current assignment, Lt Col Parker served as Commander, 21st Special Tactics Squadron, Hurlburt Field, Florida.

End notes available on request