Foreign Area Officers’ Perspective on Security Cooperation Organizations and the Defense Attaché System: Observations, Inefficiencies, and Proposed Solutions

By Lieutenant Colonel Romeo Cubas, U.S. Marine Corps; Lieutenant Colonel Robert Sean Tompkins, U.S. Army; and Major William Morse, U.S. Air Force

Introduction

The Security Cooperation (SC) and Defense Attaché System (DAS) communities continue to lead Department of Defense (DoD) efforts around the world as the nation seeks closer collaboration with foreign partners. The Trump Administration’s America First Policy and its reevaluation of permanent force projection levels and overall global investments are undergoing increased scrutiny, especially in this era of constrained resources. Effectiveness and productivity are balanced against a multitude of long-established policies and practices and the need for transparency, in a resource-constrained environment. In this environment, optimistic and resilient SC and DAS personnel downplay their concerns attributing their organization’s performance shortfalls to bureaucracy, task saturation, or interagency challenges, while working to correct and remove bureaucratic obstacles over time. In reality, regulatory obsession, procedural fixation, and institutional risk aversion set and reinforce conditions for inflexible and prescriptive SC and DAS organizations. As the DoD looks to maximize efficiencies and stretch resources, these negative tendencies need to be corrected or unintended consequence will hinder U.S. foreign policy.

Foreign Area Officers (FAO) serve unique roles in advancing U.S. foreign policy, gaining access to partners and allies and executing national programs overseas. FAOs’ access and exposure to foreign militaries, governments, and cultures give them unique perspectives and expertise. Their perspectives on SC and DAS efforts need to be considered as DoD reevaluates the role SC will play both in Theater Campaign Plans and, in a larger context the global stage, to best achieve national objectives. Security Cooperation Offices (SCO) and Defense Attaché Offices (DAO) should have the latitude to select a unique management structure based on mission priority, operational tempo, and the occupational specialties, training, and skills of their staffs. Central to this key point is the ability to gain and maintain access to respective partner-nation counterparts and the necessity to operate quickly and effectively in a dynamic operational environment.

While DoD has mandated structural changes in the SC and DAS communities to capitalize on efficiencies, implementation as directed is not feasible. To minimize friction and achieve these efficiencies, DAS and SC communities must address three key principles: sound leadership fundamentals, efficient resource management, and streamlining organizational structures. Espousing these principles ensures that the DoD will maintain the ability to advance U.S. interests abroad while effectively utilizing FAO resources common to the SC and DAS communities.

Office Fundamentals

Whether a civilian business or military command, successful organizations require structure, leadership, workforce performance, and accountability to perform effectively. Additionally, when working in a complex joint and interagency environment, simple management structures support unity of command and unity of effort via unambiguous reporting chains, effective communication, and strong working relationships. Convoluted reporting chains and funding streams unnecessarily confound the complex intergovernmental and interagency environment that FAOs operate in.

A SCO or DAO may be aligned along functional disciplines in what is known as a matrix model or around particular programs. Regardless of the chosen structure, proficiency, accountability, and strong leadership are critical to the effectiveness and efficiency of the organization.

The Matrix Model vs. The Program Centric Model.

Many public and private sector professionals prefer to organize their teams using a typical business matrix structure. This management approach segments an organization into professional disciplines such as program management, contracting, engineering, and logistics. A SCO or DAO could assimilate this structure to a standard battalion-like construct with staff functions such as administration, intelligence, operations, and logistics. To some extent, larger SCOs, like those in Saudi Arabia and Colombia, operate under such a staff structure. Under a functions-oriented arrangement, employees receive guidance from separate department heads or function leads. The department heads then report to the Senior Defense Official (SDO).

This command and control (C2) structure can be further complicated and convoluted in large, unique, and/or legacy organizations such as those in Saudi Arabia. In Saudi Arabia, U.S. Central Command considers the U.S. Military Training Mission (USMTM) to be the primary SCO. However, there are two additional military training missions in country. The USMTM as well as the Office of the Program Manager (Saudi Arabian National Guard) and Military Assistance Group (Ministry of the Interior) are all geographically separated from the embassy.

Only recently has the two-star Senior Defense Official/Defense Attaché (SDO/DATT) - formerly the Chief of USMTM - taken measures to task-organize the entire DoD team, including the DAO. Previously, the Saudi Country Team’s functions-oriented model, coupled with compartmentalization, C2 disunity, and four geographically separated organizations, proved to be problematic. The recent changes are expected to create positive outcomes. Understanding this conundrum, the SDO/DATT, with support from the Country Team and U.S. Central Command, stood up an additional Office of Military Cooperation (OMC) to attempt to bridge the C2 gap and better integrate DoD into the Country Team. A strong C2 structure sets the foundation for improved human resource management and maximizes effectiveness.

Proponents of a typical matrix organization argue that it is unhealthy for an organization to monopolize technical talent or stifle employee growth by constraining employees to a specific project or task. The matrix structure has its benefits and drawbacks as well. On one hand, a matrix structure enables professionals to expand their horizons by supporting a variety of efforts and participating in multiple Integrated Planning Teams (IPTs). Employees may also benefit from more training opportunities and clearly defined career paths within their assigned specialty. On the other hand, when a competent individual is in support of several lines of effort or participates in various IPTs, as is common in an embassy environment, he or she may be unavailable during critical moments and unable to support high priority programs. Moreover, leaders may find it challenging to effectively manage personnel and will inevitably allocate manpower based on ad hoc priorities when confronted with shortages. SC and DAS professionals also juggle multiple projects simultaneously and run the risk of duplicating efforts, and might only possess superficial knowledge of their various programs.

Many of the more robust DAOs, with a full complement of attachés and assistants, tend to follow a matrix model, and they typically employ their FAOs as regional experts and service generalists. While this approach has proven to be effective in the attaché community, it is increasingly challenging in the SC arena where programs require an in-depth knowledge of programs and regulatory guidance and program continuity. This is especially true considering the many complicated authorities, funding streams, legal restrictions, and country-specific nuances that shape each SC program (i.e. Foreign Military Sales (FMS), International Military Education and Training (IMET)). In this context, SC might thrive under a more knowledge-based and specific program-centric construct.

Under a program-centric structure, SCO and DAS professionals must become intimately familiar with the details of a particular project or partner-nation organization. FAOs will usually have excellent communications with their local counterparts throughout the program’s lifespan or duration of a professional relationship. Moreover, the dedicated or solid-line reporting chain of a program-oriented approach reduces the likelihood of personnel being reassigned because the Program Manager controls his or her personnel and is their direct supervisor. Functional managers would not be able to task or reallocate SCO or DAS personnel since they are not their direct supervisors and have no decision-making authority over individual programs. For these reasons, this methodology enhances a program’s stability, reduces administrative tensions, and increases the probability of success.

Employees fully invest themselves in a particular project because they know that it is a long-term assignment. However, this management structure has risks, and it is possible for staff to become stove-piped. As a result, lessons learned and effective program management techniques may not be shared throughout the organization. Manning and funding constraints can exacerbate these tendencies.

Every SCO and DAO is resourced based on the priority it is given by the DoD, Department of State, and the Combatant Command (COCOM) to which it belongs. In the dynamic interagency/ intergovernmental environment in which SCOs and DAOs operate, resource levels are especially pertinent. The environment changes very quickly based on any number of variables beyond U.S. Government (USG) control (e.g., partner-nation elections). Yet, human and funding resources are planned two to three years out and are slow to adapt to such changes or shifting Ambassador and COCOM priorities. Here, both DAO and SCO leaders will have to balance workforce manning levels, mission priorities, and the desired effectiveness of his or her various efforts when determining the most appropriate management structure to follow.

In light of the dynamic operational environment and varied resource levels among embassies, SDO/DATTs need to be able to tailor their organizational structure to their particular circumstances. DoD has directed organizational changes; however, they often require coordination above the SDO/DATT’s level of authority.

Organizational Changes

In 2013, DoD Directive 5205.75 directed changes to the DoD footprint at embassies worldwide. It also instituted the SDO/DATT concept that empowered the ranking attaché to coordinate SC and DAO activities while serving as the Chief of Mission’s (COM) military advisor. Four years later, change 1 to the Directive mandated that each SDO/DATT identify efficiencies to be gained by eliminating redundancies between their SCOs and DAOs. While there are efficiencies to be gained, SDO/DATTs lack the authority to implement the most meaningful changes due to manning and service-specific and institution-imposed limitations. Meaningful transformation can only be accomplished if .the Under Secretaries of Defense for Policy (USD(P)) and Intelligence (USD(I)), the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), and the COCOMs coordinate the management of a combined SCO-DAO structure. In short, “the current system is succeeding more because of the professionalism and adaptability of its members than because of the structure of the organization.”

According to this Directive, the SDO/DATT, who is typically the highest-ranking DoD official in country, has coordinating authority over all COM DoD personnel and leads the SC efforts of the SCO as well as the DIA activities of the DAO. However, these two organizations are perceived to have disparate and mutually exclusive mission sets. On one hand, DAOs are, by design, intelligence focused, and their participation in SC may discourage openness and transparency. Moreover, the DIA does not want attachés distracted from their primary prescribed mission. On the other hand, SCOs do not want their cooperative relationships leveraged for increased partner nation access by the DAO. Additional challenges in merging DAO and SCO offices may include office heads potentially having equal ranks with equally important missions, necessitating someone senior to adjudicate the merits of each in support of the unified DoD/Country Team effort.

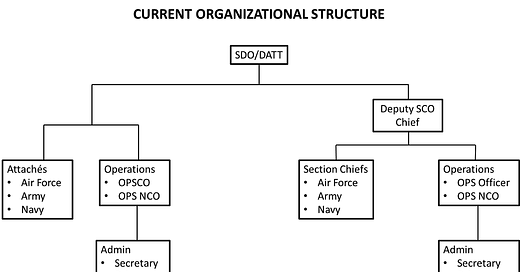

Despite these concerns and competing interests, changes made to the SDO/DATT concept were a welcome change. In 2016, a group of SDO/DATTs from one COCOM collectively identified several efficiencies that could be gained in alignment with and support of the new Directive. However, many of the initiatives identified by these leaders will still require institutional leadership to effect true transformation. In a 2007 Naval War College thesis regarding organizational realignment, U.S. Army Major Paul Sigler recommended a central headquarters for FAOs and that DAOs align with COCOMs. A better organizational model could enable embassy DoD teams to be more efficient, particularly in personnel and resource management, with the added benefit of better managing members of the FAO career field. Currently, while the SCO and DAOs both report to the SDO/DATT, they still function largely independently with separate support staffs. These staffs include Operations NCOs, drivers and locally employed staff managing office finances, SC programs, and secretaries. By combining common functions, DoD offices within an embassy country team would decrease the total required manning, reduce duplication of effort, and ultimately save money. The diagrams below demonstrate these two principles.

(Diagram 1: Current typical structure. Note the repetition of secretaries, drivers, OPS NCOs and military branch section chiefs. In a large embassy larger staffs may be necessary. In a small embassy, efficiencies can be gained by “dual hatting” some or all positions.)

(Diagram 2: In this structure the SDO/DATT has the flexibility to organize along service branch specialties. It also flattens the organization; reducing the supervisory burden on any one echelon. In a large embassy all of these positions may be filled allowing service specialist to support each other’s activities. In a small embassy the Naval Mission might consist of one person covering all Navy-related tasks. Also note the single support staff.)

In many cases, establishing a single higher headquarters is an effective way to organize and employ a group with unique skills and missions. Perhaps the best model of this approach is U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM). This organization has a structure that could be adapted to the FAO community, although significant drawbacks exist. USSOCOM functions as a unified command whenever component Special Operations Forces (SOF) must work together. It also helps to develop the careers of specialized military members and ensures that their skills are represented in higher command echelons. A FAO headquarters could also unify and simplify the DAO/SCO chain of command. Furthermore, the FAO mission is a fraction of the size of the SOF mission, both in terms of personnel and specialized equipment, so perhaps a better alternative is to instead move the attaché mission to the COCOMs.

Moving the attaché mission to the COCOMs has several benefits and minimizes bureaucratic costs. Benefits include a simplified and unified chain of command, streamlined resource distribution, and improved holistic management of the FAO community by the stakeholder COCOM. This type of oversight would enable the COCOM to better facilitate In Region Training programs, enhance language proficiencies, ensure that job-specific training and prerequisites are met, and monitor region-specific advanced education. Moreover, it would ensure that FAOs remain dialed into current regional issues, trends, and developments.

Leadership and Training

An SDO/DATT will select a management structure based on the value they place on functional specialization, the number of programs and personal relationships they have to manage, and the level of risk they are willing to assume. To be effective the organization needs a competent workforce guided by capable, experienced, and trained leaders. These individuals succeed when they are empowered by a leader who trusts and is trusted by the entire workforce. Unfortunately, SCOs and DAOs are laden with multiple gatekeepers from within the country team, parent agencies (Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) or DIA), military components and COCOMs. Regrettably, these bureaucracies add layers of oppressive oversight, conflicting guidance, and disassociated metrics making it difficult to accomplish even the simplest of tasks. Convincing an organization that is feverishly trying to overcome these bureaucratic hurdles to accomplish the COM’s objectives demands continuous patience and strong leadership. The SC or DAS leader has to ensure that the DoD workforce is appropriately sourced and adequately trained to carry out their duties. However, this is often outside their span of control.

On one end of the spectrum, the DSCA workforce within a SCO is typically comprised of professionals from various backgrounds and specialties depending on the service that sourced the particular joint manning billet. Some of these officers and enlisted personnel may not even be FAOs; instead, they are sourced directly from operational forces. This is more frequently the case with the Air Force and Marine Corps. Often times, personnel are assigned who have limited foreign language proficiency, no acquisitions or country team experience, and no training from the Defense Institute of Security Cooperation Studies (DISCS). Untrained individuals are often assigned due to the lack of availability of FAOs with SC and language capability. As such, their effectiveness within a SCO is limited. These Airmen and Marines generally neither possess the necessary baseline knowledge of acquisitions, FMS, and IMET, nor the experience needed to handle foreign contractual issues, such as those required for counter-narcotics or mobile training teams. However, their determination, initiative, judgment, and leadership skills tend to mitigate any experience gaps, albeit with a steep an inefficient learning curve.

On the other end of the spectrum, the DAS mandates that all of its personnel (officer, enlisted, and civilian) complete minimum formal training requirements and attend the Joint Military Attaché School (JMAS) before going abroad. Unlike SC programs that can be very niche and specialized, JMAS provides a comprehensive mix of operational, legal, administrative, and diplomatic training to its students. Most importantly, JMAS provides a common vernacular, introduction to common systems and processes, expectation management, and a standard baseline for all DAS personnel early on, prior to an assignment.

Marine Corps officers do not generally become FAOs until at least the rank of major, do so as a secondary specialty, and are expected to return to an operational unit after their FAO tour. At this point in their careers, Marines in ground combat specialties have generally led organizations of approximately 300 troops. Their prior experience and leadership gives them greater credibility with their partner-nation military counterparts, civilian SC employees, and contractor personnel. However, like the Navy, the Marine Corps does not generally value FAO tours as much as operational billets. FAOs are generally not chosen for command and have lower promotion rates above the rank of lieutenant colonel. The Marine Corps and Air Force’s dual-track system seriously impedes FAO management and officer career development. As an example, there are multiple cases of Marine Corps captains training for three to four years as FAOs and then returning to their primary military specialty even before their first FAO utilization assignment. The Air Force faces a similarly dysfunctional process. Air Force officers who chose to become FAOs generally do not achieve promotion above the rank of lieutenant colonel.

While not always the case, Naval officers assigned to a SCO or DAO wrestle with a different challenge. Despite the fact that they possess the same basic language, SC, and/or DAS training and qualifications, they generally do not have leadership and command opportunities compared to their Army, Air Force, or Marine Corps colleagues. Navy officers typically transition to the FAO community as junior lieutenants (O-3), with relatively little leadership experience compared to their colleagues from other services. Moreover, there is a general perception that the Navy does not value joint or non-standard billets and views these career choices as professional dead ends. Army officers become FAOs as senior captains (O-3) or junior majors (O-4). Unlike their Navy brethren, they have typically accomplished at least three company grade leadership (e.g., platoon leader) and primary battalion staff assignments, including commanding at the company level, and like their Marine Corps counterparts enjoy the privileges of significant small unit leadership experiences, especially in ground combat specialties.

The SC and DAS environment requires leadership experience from all of its military members, regardless of their branch of service. Language proficiency, acquisitions experience, and successful completion of SC training should accompany this leadership experience before personnel are assigned overseas. In order to develop a more competitive workforce, SC billets should also be “A” coded as acquisition billets, further diversifying FAO qualifications. These qualifications should be tracked to screen, source, and maintain a professional corps for the SC and DAS communities, similar to the Army FAO program. Expanding the knowledge base with DISCS-trained individuals who are capable of speaking their assigned foreign language and equipped with sufficient leadership experience will also lead to a more effective workforce.

SC and DAS FAO professionals must also appreciate, understand, and effectively empower subordinates. Most successful FAOs, relying on prior leadership and command experience, realize this. Judicious and resolute decision-making that accompanies good leadership ripples across an organization and results in a positive environment where initiative is encouraged and a sense of urgency prospers. However, the fact that there is no standardized set of qualifications or common staffing denominators amongst the services for FAOs is inefficient and challenges leadership.

Resource Management

As departments and agencies seek to maximize efficiencies in a perpetually budget-constrained environment, DoD organizations within many country teams often find themselves competing with, rather than complementing, each other for resources and relevance. While this point may be an oversimplification, as each country team is unique due to its priority, size, and personalities, it is still a significant enough topic to explore. Both the DIA (parent to all DAOs) and the DSCA (parent to the various types of SCOs) work to advance and protect U.S. national security interests and influence abroad. Although these are the fundamental purposes of their existence, these two separate and distinct entities possess inherent structural and cultural differences with a diverse array of authorities, qualifications, and resources (means) to execute their separate missions. In many countries the intentionally separate roles, responsibilities, and relationships between both DAO and SCO officers and the partner nation can become conflated and confusing, at least from the partner’s perspective.

The SCOs benefit the partner nation by building capacity through Foreign Military Financing (FMF), IMET, and presenting opportunities to train. While the SCO-partner nation relationship is automatic, the DAO exclusively fulfills the diplomatic and representational role and is often viewed with caution and skepticism. This perception poses challenges to the SDO/DATT construct. The deliberate shift over the past decade to nest all DoD organizations under a single authority has streamlined inter-office coordination with a less ambiguous leadership structure. However, resource management, legal, policy and authority constraints are still not optimized to fulfill competing requirements from higher headquarters. Updated guidance to the DoD Directive ordered further consolidation of common DAO and SCO functions. The update aims to consolidate to the “maximum extent possible […while preserving] distinct missions, funding streams, and information sharing environments.” These directions are still very aspirational and are hampered by institutional resistance from DIA and DSCA managers fearing unintended consequences and mission impact (e.g., complicating long-standing programs and relationships, restricting access, competing for resources, etc.). In cases where these alignments are taking shape and proving to be effective, it is often due to like-minded personalities forcing the issue out of necessity, not due to an institutional shift in structure or mindset.

As further codified by DoD Directive 5132.03, the SDO/DATT is the “Chief of Mission’s principal military advisor on defense and national security issues for all DoD matters involving the embassy or DoD elements assigned to or working from the embassy and… can be the defense attaché or the chief of the SCO.” Although dual-hatted, it is impractical for the SDO/DATT to be expected to fulfill both DIA and DSCA roles equally “under the joint oversight and administrative management of the OUSD(P) and OUSD(I) through the Directors of the DSCA and DIA, in coordination with the respective Combatant Command.”

In addition to the COM and his/her specific service, the SDO/DATT answers to multiple other masters (e.g., COCOM, DIA, DSCA) while simultaneously addressing the needs of Congress and the partner nation. While full DoD integration of both DAO and SCO organizations would be an ideal model for synchronizing operations, managing resources and accomplishing a variety of additional tasks (e.g., visit control and exercise support), the reality is that the mechanics and bureaucracy to effectively integrate both structures is extremely difficult at the country team level. This issue could be mitigated by an integrated command structure.

Underscoring the complications of integration is the fact that SCOs have to manage multiple funding streams and authorities, separate from those used by the DAS. For example, DoD operations are funded through U.S. Code Title 10 while State Department programs are funded by Title 22 authorities. Additionally, misaligned and competing specified tasks, missions, and metrics for success (DSCA vs. DIA) and tailored general support requirements make this goal difficult to achieve. In the final analysis, integrating the SCO and DAO is possible and worth exploring, but a concerted effort must be driven from the top down.

More importantly, these challenges are amplified by the fact that the different services continue to populate their attaché and SCO ranks with officers of varying degrees of experience, training, and qualification from both FAO and non-FAO communities. These issues should be standardized across the joint force. While SCOs and DAOs are inherently joint, reliance on short-tours to fill positions, service-specific priorities (e.g., promotion wickets and timelines), and lack of training has led to an over-reliance on on-the-job training. These ad-hoc staffing practices cause organizational inefficiencies and loss of continuity that disproportionately affect SCOs. From a joint-force and whole-of-government approach,

this directly contradicts the Unity of Effort principle, especially if SC is “at the root of national security issues” and integral to the effective execution of policy in support of national objectives.

While equally important, DAO members contribute to the intelligence community and national defense by serving as “overt…collectors of military and political-military information” and are equally vital to national security from a DIA vantage. Without question, DoD-wide integration and alignment of priorities must complement multiple national defense, security, and military objectives. Unfortunately, due to a poor management structure and finite resources, both the SCO and DAO organizations find themselves “building an airplane in flight.” Despite these challenges, SC and DAO professionals understand the benefits of leveraging each other, building relationships, avoiding redundancies, and maximizing efficiencies wherever possible to support the COM and to achieve national objectives.

Conclusion

The DoD’s drive for mandated efficiencies in the SC and DAS communities depends upon proficient leadership, a trained workforce, and a tailored organizational structure. Currently service components and COCOMs are not doing enough to professionally develop the FAO, SC, and DAS workforce. In addition to maintaining proficiencies, these commands and parent agencies should oversee FAO selection. Central oversight will ensure officers with the right competencies are selected for the complex SC and DAO environments. When a workforce is not proficient, the institution suffers from a culture of complacency. To meet the demanding operational requirements in a high-pace, resource-constrained environment, a pool of trained and empowered leaders must be available. The workforce must then be employed and set up for success by receiving clear and consistent guidance from a unified command structure, much like a frontline military unit.

Professionals in SC and DAS organizations ultimately want to improve their interactions with the partner nation and meet the objectives laid out in their Theater Campaign Plans. The DoD has emphasized changing the organizational structure of SC and DAS in its attempts to gain efficiencies, but leadership failures will lead to an ineffective workforce and resource mismanagement. These challenges can be overcome by a culture that fosters initiative, selflessness, and rewards those that seek efficiencies in a joint, interagency, and multinational environment. To create this culture, the DoD needs to focus on leadership development and a unified organizational structure.

An organization’s bid for success begins with its selection of a management structure, since it will define chains of command, clarify working relationships, facilitate communications, and help a team cope with risk. The success of a program depends on competent team members, efficient processes and, procedures, and a positive organizational culture. There is not a “one size fits all” solution to seeking efficiencies in a SCO or DAS office. The size of an organization or project will play a major role in determining the ideal management structure. Smaller activities with direct reporting channels can be more effective when offered in conjunction with vertical management or functional structures that depend on a traditional command concept. In contrast, a large program may be multilayered and complex. Its members may be quickly overwhelmed or technically unprepared. In this case, a matrix organization, where control still remains with the manager, may be better suited, since the program can benefit from the expertise of professionals within a particular competency.

The benefits of unifying the chain of command for both the SCOs and the DAOs provide multiple benefits in cost savings and mission enhancement. Inherently there is some conjecture that involving attachés, with their intelligence focus, discourages partner nations from security cooperation and that the DIA is cautious to have attachés distracted from their primary focus. No other nation involved in SC arena, however, separates the two missions and partner nations are often confused by the procedural differences between the two offices. Involving the DAO in SC will result in more access for the DAO and allow the SDO/DATT to employ personnel in the most effective way while eliminating staff and resource redundancies.

Regardless of the selected management approach, it is undeniable that an organization’s effectiveness is directly related to the quality of its leadership and its willingness to hold its workforce accountable. When people are empowered to do their jobs and held to a standard, a culture of trust, effectiveness, and efficiency prospers throughout the institution. An employee that is trusted, valued, and respected as an important team member is also more likely to put forth extra effort. Strong leadership clearly sets the tone and creates an effective and efficient work environment that has positive successive effects leading to more efficient resource management and the streamlining of an organization’s structure.

About the Authors

Lieutenant Colonel Tompkins is a Middle East Foreign Area Officer. He has been an ordnance and logistics officer and then an attaché and staff officer. He recently completed an assignment as a Joint Staff (J5) Political-Military Planner and is en route to the Office of Military Cooperation, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Lieutenant Colonel Cubas is a Latin American Foreign Area Officer. with experience in armor, supply, acquisitions, and security cooperation. He recently served as the Naval Mission Deputy and Marine Corps’ Representative to the Security Cooperation Office, U.S. Embassy, Bogotá, Colombia and was recently selected to the Defense Attaché System. Major Morse is a Latin American Foreign Area Officer. He is a KC-135 pilot and served as an exchange officer with the Spanish Air Force. Major Morse serves at the Defense Cooperation Office at the U.S. Embassy in Asunción, Paraguay.