FAO Retrospective; DAO Rangoon During the 8-8-88 Uprising

By Colonel John B. Haseman, U.S. Army (Retired)

Editor’s Note: The FAO Journal is pleased to bring you snapshots of yesteryear, told by FAOs of their experiences and offering readers to view historical events through contemporary lenses.

Author's Note: Portions of this article were published separately in different format and length in the Military Writers Society of America 2023 Anthology Snapshots, and AFAOA Newsletters March and September 2024.

I became a Southeast Asia Foreign Area Officer (FAO) in 1974, shortly after the program was established after the end of the Vietnam War. FAO assignments filled the last twenty years of my army career. My assignment to Rangoon was my seventh consecutive FAO posting. I began my assignment as the U.S. Senior Defense Official/Defense Attaché (SDO/DATT) to Burma in May 1987 and arrived in Rangoon just a week after Ambassador Burton Levin. We formed a terrific team for the ensuing three years of tension, violence, and dictatorial pressure from the ruling military junta.

Rangoon in the 1980s was 50 years behind nearby Bangkok, Thailand in terms of economic development, infrastructure, standard of living, and creature comforts. I enjoyed my Burma assignment, with its distinctive culture, wonderful people, and beautiful unspoiled countryside.

I was chief of a five-person Defense Attaché Office (DAO). The DAO's other members included Air Attaché Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Ron Facundus; an Army Chief Warrant Officer 2 (CW2) Operations Coordinator; an Army Sergeant First Class (SFC) Operations NCO; and an Air Force Staff Sergeant (SSG) Administrative NCO (a position unfilled from July through November 1988). The embassy staff also included the six-man U.S. Marine Corps Embassy Security Guard Detachment. We all benefited from the outstanding leadership of Ambassador Levin.

Burma's draconian military junta government had an egregious human rights history. Everyone in the small international diplomatic community had stories to tell of violence or other disturbing incidents between the government and its citizens. But nothing prepared me for the events on 8 August 1988 (forever after known as 8 - 8 - 88, Burma is hugely influenced by numerology) and the two months that followed.

Tensions in Rangoon began to rise back in September 1987, when the government suddenly devalued the three largest-denomination currency bills without recompense. Millions of people lost their life savings. Army and police squads brutally repressed student-led protests. Police raped university students and beat anybody they pleased. Very small anti-government demonstrations broke out and were quickly dispersed. Fear permeated the people, including the Embassy's Burmese staff. The American staff, on edge, shared this turbulent experience.

In late July 1988 Burmese dictator General Ne Win suddenly announced his resignation from all of his positions, and the ruling military junta appointed the general known as the "Butcher of Rangoon" as the new junta leader. Large anti-government demonstrations began immediately and occurred almost daily, including in the plaza in front of City Hall, directly across Independence Square from the American Embassy. At first the government tolerated the demonstrations - very unusual for Burma - where police or army units quickly broke up anti-government protests of any size.

It was an ordinary morning in Rangoon on this fateful day, 8 August 1988. I left for the embassy at about 0715. Before my driver, U Hla Myint, and I had traveled even two blocks, a frantic call came over the car radio:

"Help, anybody hearing, help! I’m on Boundary Road in the middle of a huge crowd of Burmese, and the Army is shooting at me. Anybody hearing this, please help."

It was "Len," the Embassy Administrative Counselor calling for help. We were only minutes away from the trouble spot, so I told the driver to step on it. On the radio I told Len to lie on the floor of his car where the engine block would give him some protection from bullets. We neared the danger area driving north on U Wisara Boulevard, a divided four-lane parkway with a grass-and-trees median strip. As we approached the four-way intersection with Boundary Road I opened the rear passenger side window and heard the distinctive pop-pop-pop of rifle fire. I and immediately saw at least a dozen soldiers in the intersection and on the triangular-shaped "island" between the main travel lanes and a right-turn lane onto Boundary Road. The soldiers were shooting into a large crowd of civilians fleeing east on Boundary Road, where my embassy colleague was trapped amid this crowd.

U Hla Myint pulled partly into the right-turn lane and stopped, but kept the engine running. Soldiers blocked the road and many more stood on the “island.” I took my diplomatic ID card out, left the car -- leaving the rear passenger side door open -- and slowly approached the soldiers. They quickly noticed the big white Chevrolet sedan with diplomatic license plates and the tall Western man walking towards them. The rate of fire from the soldiers shooting down the street at fleeing Burmese and the Administrative Counselor's car slowed but did not stop. Many of the soldiers turned to stare at the unexpected interruption and many shifted their rifles to cover me.

The officer in command was a lieutenant or captain, I don’t recall. I showed him my diplomatic ID card, identified myself, and in my not-so-great Burmese but in my very best military command voice I demanded the soldiers stop shooting "at an American diplomat in an American diplomatic automobile.” I repeated the demand, firmly, in English, with gestures pointing down Boundary Road toward the trapped Admin istrative Counselor's vehicle.

The officer told me (in Burmese) that I was interfering in a military operation, and to leave immediately. I again demanded that the soldiers stop shooting at an American Embassy vehicle. Very angry, the officer shouted loudly "You! Go! Now!" in English this time. By then the shooting had stopped, but too late for the dozens of Burmese lying in the street, dead or wounded from rifle fire. Then I heard another soldier tell the officer, in Burmese, “We could shoot him and claim it was an accident.” My driver also heard that, and called out to me: “Sir, we need to get out of here right now.”

I was ready to leave! I walked slowly to the passenger side of the car but never turned my back on the soldiers. Several of them put their hands on me and shoved me into the sedan's still-open rear passenger seat. I pulled the door shut. One soldier stuck his rifle barrel through the open window. I told U Hla Myint to back up and get us the hell out of there. The Administrative Counselor meanwhile had taken advantage of the lull in shooting and backed his car 100 yards or so to the three-way intersection with Inya Road and drove away.

U Hla Myint backed up, turned quickly, and headed south toward the embassy in the northbound lanes (driving the wrong way!) on U Wisara Boulevard. I used the car radio to alert everyone of violence on the streets and instructed everyone to return to their quarters and not to attempt to drive to the Embassy. At that point I did not know the situation elsewhere in the city. That confrontation at Boundary Road provided the first indication any American diplomat had about violence on the streets of Rangoon that morning.

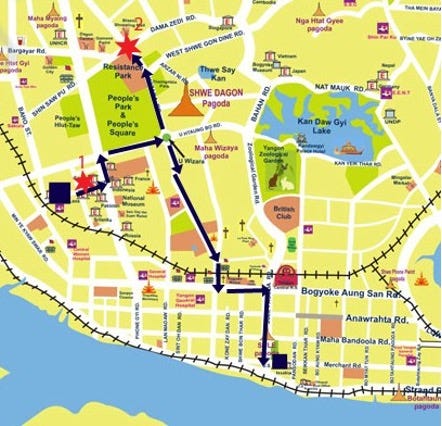

Left side black square is DATT residence. Bottom black square is the U.S. Embassy. Red 1 star is my location when I received radio call for help. Red star at top is location of shooting. Black line shows route driving to scene of shooting and then down to the embassy.

At the Embassy I went quickly upstairs to the ambassador's office, telephoned Ambassador Levin, and described what had happened. He opened our telephonic notification system and told all Americans to remain at home until further notice.

The Deputy Chief of Mission (DCM) took charge of the few staff who had already arrived at work and put a call through to the State Department in Washington on what became an open line for the next two days. A senior embassy officer and I went up onto the roof of the embassy, where a sturdy wooden platform built between two window gables provided a view across Independence Square toward City Hall and Sule Pagoda. We saw and heard the unfolding of a great tragedy. We could hear the steady popping of rifle fire and could see many people running in all directions to get away from City Hall. We expected very heavy casualties.

I telephoned the Chief of the Armed Forces Foreign Liaison Office (FLO) and delivered a formal protest about the shooting on Boundary Road that endangered the life of an American diplomat, and my treatment at the hands of the soldiers there. I told him what I had observed and done and emphasized my official protest of shots fired at an American diplomat and Burmese soldiers putting their hands on an American diplomat.

The FLO immediately issued a formal verbal protest at my actions “interfering with the proper duties of the “Tatmadaw." "Tatmadaw" is a Burmese word that refers to the entire armed forces establishment. News had traveled fast from that officer at Boundary Road, at least he had correctly reported who I was! The Burmese official diplomatic note criticizing my behavior arrived at the embassy later that afternoon.

A steady flow of Burmese called the embassy to give information about what happened that day. A large anti-government demonstration at the Shwedagon Pagoda, the most important religious edifice in Burma, had just ended. Overnight the government had issued orders to the army and police to use violence to break up demonstrations. The army unit I had met at Boundary Road was just one of many that had opened fire on unarmed gatherings. The military junta declared martial law, forbade any gathering of more than five people, and began a curfew from 1600 to 0800 hours initially.

A Deep Breath: 9 August 1988

The next day Ambassador Levin and most American and Burmese staff came to work. Staff collected reports about violent incidents happening all over the city as well as in other major cities. We expected casualties in Rangoon alone to be in the thousands. Ambassador Levin changed embassy work hours to begin at 0900 and close at 1500 so everyone could returnget homme and get off the streets before curfew began at 1600. The State Department instructed Ambassador Levin to be available for a phone call with the Secretary of State and possibly with President Reagan, at a suggested time after curfew. I called the FLO and asked for a one-time exception to the curfew so the aambassador could speak with very senior American officials in Washington. A few hours later the FLO called back with a one-time exception to the curfew and gave specific routes for diplomatic vehicles to travel from the embassy to homes.

Ambassador Levin did indeed speak with the Secretary of State, and at approximately 1745 we formed a small convoy to return the few of us remaining on duty to follow the routes specified by the FLO. I rode in the first vehicle, my official sedan, but riding in the front passenger seat instead of the back seat so I could more easily use the car radio. Ambassador Levin and the DCM followed in the Ambassador's official vehicle, a distinctive Cadillac sedan. An official embassy minivan with two U.S. Marines and two embassy officers followed. We left the embassy and turned north on Sule Pagoda Road, around the Sule Pagoda roundabout, and north on this main artery. But after only one block we encountered a barbed-wire barricade manned by soldiers and backed by an army tank with its barrel pointed right at us.

I used the car radio and told everyone to remain in their vehicles with windows closed. An army captain approached me, I opened the window and identified myself in Burmese, showed my diplomatic ID card and identified the others in the convoy. The captain told me in Burmese that we were under arrest for violating the curfew. I told the captain that we had permission from the Tatmadaw leadership and told him to check with the Chief of Intelligence, the very powerful and much-feared Colonel Khin Nyunt. The captain switched to excellent English, told me to wait and for nobody to move, and he walked behind the blockade. He returned a few minutes later and confirmed our permission for this one-time trip. He ordered us to go home and be off the streets within 15 minutes. Soldiers pulled the barricade open and our convoy sped away, the only vehicles moving on Rangoon's largest street. We made it home in time, and that was the last time the embassy requested permission to break curfew. After a few days authorities shortened the curfew to 1800 to 0600.

The Following Weeks

Ambassador Levin requested an immediate appointment with the Burmese Minister of Defense. The ambassador and I went together for that appointment, and to many subsequent official calls during the violent months of August and September and for most of the remaining months of our assignments. We wanted to remove any thought that the Burmese military government might have that the U.S. military would support their actions as “fellow soldiers.” By having the civilian ambassador and the defense attaché together, we made it clear that the entire United States Government followed the same policy and that the Burmese government would receive no sympathy from U.S. military leadership.

When we arrived at the Tatmadaw guest room the navy chief of staff received us rather than the defense minister. The ambassador delivered a firm demarche calling for the army to stop shooting unarmed civilians. The admiral responded with a chilling sentence of only eight words:

"First the people must be made to obey."

Shooting incidents continued sporadically for more than a week. Within a few weeks, however, soldiers and the police had disappeared from the streets. The lull in violence against the people of Rangoon puzzled us. Where had the police gone? Where was the army? Why had all the security forces suddenly left the streets? We did not know the answers to those questions.

While we felt relieved that the shooting of unarmed civilians had stopped, we now saw the start of a disturbing period of revenge-taking by an angry population. Many Burmese incorrectly felt they had "won" and defeated the country's security forces. The embassy received a continuous stream of reports of bloody reprisals against known and suspected intelligence agents and police informants. A mob stopped the embassy van returning a shift of Marine Security Guards to their quarters and forced them to witness the beheading of a suspected intelligence agent. I received a hand-delivered VHS cassette tape of the beating, torture, and beheading of another unfortunate man. Such incidents made it a very unpleasant time in Rangoon.

A groundswell of spontaneous demonstration marches all over Rangoon surprised us even more. We often saw groups of dozens of people walking together with anti-government and pro-democracy banners and signs. Well-organized pro-democracy demonstration marches passed the embassy almost daily, some huge, numbering in the hundreds of thousands of people. Smaller marches consisted of ad hoc social groups such as students, teachers, nurses, and government employees. Despite the rainy season processions continued, rain or shine.

The eembassy portico over the wide public sidewalk became a popular locale for pro-democracy speeches. Crowds routinely gathered in front of the embassy, blocked the street and lined up along the fence around Independence Square. Speakers used a battery-powered megaphone. The crowds, were well-mannered and polite, made way immediately for eembassy vehicles that parked in the alley next to the eembassy, or for access to the embassy front door.

Embassy Evacuation

At the same time we began to worry about growing shortages of fuel and foodstuffs and the possibility of increased danger facing our family members. Regular economic activity slowed as inbound shipments of fuel and food stopped. Even the robust government-tolerated indoor black market had mostly empty shelves. We needed gasoline for vehicles, and for the home generators that provided electricity when Rangoon's eccentric power grid failed. Most residences had water-well pumps -- no fuel no water. A large crowd broke into the United Nations warehouse and looted it of all its stored foodstuffs and supplies. Concerned that violence

could break out against foreign diplomats amid this increasingly serious situation, Ambassador Levin decided to evacuate all family members and non-essential embassy staff to safe haven in Bangkok, Thailand until the situation improved and the security and economic risks to our family members passed.

The Embassy Emergency Action Committee (EAC) began work on plans for an evacuation, with or without the cooperation of the Burmese government. The EAC planned several alternative options. The EAC preferred to use charter flights by commercial aircraft from Bangkok. Two worst-case scenarios involved the use of U.S. Air Force transport aircraft, protected by fighters or armed helicopters, and U.S. Navy small boat transports that could sail up the Rangoon River from the Andaman Sea. The U.S. Pacific Command ordered two C-141 transport aircraft to Don Muang Airport in Bangkok to stand by in case the situation worsened. A U.S. Navy task force stood by in international waters of the Bay of Bengal, delaying its return from a humanitarian mission aiding neighboring Bangladesh following a devastating cyclone

Ambassador Levin drew up a list of essential staff that would remain in Rangoon. The list included the ambassador, political counselor, administrative counselor, general services officer, two officers from the Station, regional security officer (RSO), all six Marine Corps Security Guards, the air attaché, and me. The ambassador ordered evacuation of all other staff and all family members, more than 60 people, to Bangkok.

I informed the Tatmadaw that the U.S. Embassy planned to evacuate some staff and family members to Bangkok temporarily, and submitted a flight clearance request to fly those C-141 aircraft from Bangkok to Rangoon. The Tatmadaw summarily denied the flight clearance. We had to rely on commercial flights to Bangkok and Dacca.

Days later the situation in Rangoon deteriorated further when Mingaladon Airport workers joined most government rank and file workers on a country-wide general strike. This left no maintenance workers, refueling staff, or other support workers on duty at Mingaladon Airport. Both Thai International and Bangladesh Biman halted flights to Rangoon.

Ambassador Levin tasked the administrative counselor, the air attaché, and me to work on the logistics of getting people and luggage onto any aircraft that could make it to Rangoon. We instructed all evacuees to pack, immediately one suitcase per person and to prepare to move on short-notice to the American Club compound. The Club was secure, provided air conditioned space where people could wait, had parking space for vehicles, and was only a ten-minute drive from the airport. No pets would be moved, which caused much distress. Evacuees would move to the airport using the embassy's official vehicle fleet. once we knew what aircraft might be used, and a time of arrival.

The diplomatic community knew that the American Embassy planned to evacuate most personnel and families. Several other embassies asked to participate in our evacuation. Ambassador Levin approved them all, always with the proviso that we would move Americans first and other nationalities would be accommodated up to the capacity of the aircraft, whatever, and however many, there might be. The two largest embassies in Rangoon, those of the U.S.S.R. and the Peoples Republic of China, did not plan to evacuate.

LTC Facundus took over detailed planning for receiving, loading, and dispatching any type and number of aircraft that might come to Mingaladon Airport. The DAO sent updated information to U.S. Pacific Command on land routes of movement, the numbers of evacuees, and detailed maps of Mingaladon Airport., The DAO also and identified possible landing and docking areas for helicopters and small navy craft along the Rangoon River. All four of us continued efforts to determine what was going on throughout Rangoon, while at the same time preparing families for evacuation to Bangkok.

After several days, our eembassy colleagues in Bangkok informed Rangoon that strong pressure from the Thai government had convinced Thai International to fly a large passenger charter plane to Rangoon, configured for maximum capacity. Phone calls between Bangkok and Rangoon established the flight details, as well as plans for reception and housing for families in Bangkok. We scheduled the aircraft to arrive in Rangoon on 11 September at 1400, and to depart no later than 1700 because of the Rangoon curfew.

The Ambassador directed us to execute the embassy evacuation plan. The embassy warden net contacted evacuees with instructions to go at once, with baggage, to the American Club. The consul-general and administrative counselor reviewed passports, checked luggage, organized a passenger manifest for the aircraft, and arranged all available official vehicles to ferry evacuees to the airport. Embassy officers notified other embassies that had requested evacuation of their people.

I contacted the British and Japanese military attachés and asked them to meet me at the airport to assist with preparations. LTC Facundus and I went to Mingaladon Airport to analyze the situation and determine what extra personnel and equipment might be needed. The six marine security guards also went to the airport, along with selected senior embassy officers. When we arrived at the airport we found it astoundingly deserted: no ground staff, no refueling personnel, no ground handling equipment such as stairs to board the aircraft or lifts to load luggage into the aircraft cargo hold. By 1300, with the Thai International aircraft already en route from Bangkok, we had nothing to get evacuees and luggage into the airplane.

Suddenly the door at one of the large aircraft hangers slid open from inside and someone shoved a wheeled set of aircraft access stairs out the door. We saw nNo airport staff and nobody came outside, but clearly they were aware of developments. With shouted thanks, we quickly rolled the stairs to the selected aircraft parking spot LTC Facundus went to the tower to confirm the presence of air traffic control staff We worried that the Burmese Air Force might harass the incoming flight, or block the only runway. Fortunately that did not happen.

Just before 1400 the Thai International aircraft landed and taxied up to the desired parking place. When a cabin attendant opened the door, however, we could see immediately that the small set of rolling stairs that the hidden ground staff had surreptitiously provided would not reach the aircraft door. We would have to improvise some kind of ladder. The Japanese defense attaché contacted a Japanese construction company that was working on a project to extend the airport runway. They were hard at work, out of sight at the far end of the runway. They responded right away with a truck, four workers, and an ordinary ladder. Helpful coincidences are always welcome in any plan of action!

We manhandled the ladder to the top of the wheeled access stairs to reach the aircraft door. Two pairs of marines stood at the base of the ladder and in the aircraft doorway, where they could hand-steady women and children up the ladder. The call went out immediately to bring the evacuees to the airport, and quickly they began to arrive, – not just Americans but staff from many other embassies.

As the designated evacuation manager, I made the arbitrary decision to board Americans first (it was our project), Japanese second (their ladder!), British and Australians next (because they had asked first), and then everyone else up to the aircraft's capacity. Personnel from the several embassies, including our military attaché corps colleagues, performed crowd control, organized groups by nationality, prioritized boarding, and assisted in maintaining order.

The next problem concerned luggage. Everyone had a suitcase, but the pilot said he was not going to take any baggage. LTC Facundus solved that problem when he told the pilot that he was fully qualified as a transport aircraft commander and knew how to manage aircraft load and balance. The pilot agreed that he could supervise baggage loading.

Colleagues got everyone to line up by nationality in priority order. Several of the men organized themselves into a chain to carry luggage from the foot of the stairs to and into the aircraft hold, lifting every suitcase by hand because we had no cargo loading equipment. LTC Facundus and two marines secured all the baggage under the watchful eyes of the Thai International co-pilot. We had two operations to complete before take-off deadline of 1700: board people onto the airplane, and load the baggage.

A total of 61 American Embassy staff and families and 156 passengers of other nationalities boarded the aircraft. Nobody who wanted to leave was left behind. As the Thai International plane lifted off, we who remained behind shook hands all around -- we had done it! And still had time to get home before curfew.

Evacuees arrived safely in Bangkok, where they endured weeks of crowded conditions. Many American families stayed at the Federal Hotel on Soi 11, a former Vietnam Era R & R hotel. Teachers from Rangoon International School set up classrooms in the hotel for the children.

Work at Embassy Rangoon continued, just with fewer people. For a week or so the situation in Rangoon was unchanged – no police or military patrols on the streets and near-daily demonstrations passed the embassy and occurred through the city. We still coped with the danger posed by looting, bloody revenge attacks, and the depletion of essential commodities like fuel and food.

Violence Redux

On the afternoon of 18 September (note the numerology: 1 + 8 = 9, 9th month), I was sitting in my residence with several Burmese friends watching the local evening news on television. Suddenly, a dramatic interruption: a uniformed army officer replaced the female news reader on the screen. In a stern voice he read an announcement that the Tatmadaw had taken control of the government, announced a dusk- to- dawn curfew effective immediately, and declared that no gatherings of more than five people would be tolerated, thus no more demonstrations. The new government called itself the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC).

The next morning the military and police returned to the streets in force. The populace, still full of confidence and spirit, continued to mass for demonstrations, and once again as on 8-8-88, soldiers opened fire on demonstrators without warning. A crowd had formed at the Sule Pagoda roundabout just adjacent to City Hall. Standing on the narrow roof-top platform at the eembassy, we could hear the steady pop- pop- pop of rifle fire as the army shot into the crowd to disperse the demonstrators in front of city hall. An organized formation of soldiers opened fire on the crowd around Sule Pagoda and began marching in formation down Sule Pagoda Road toward the embassy, sweeping the crowd before them, front ranks shooting continuously.

This time the eembassy itself became the site of violence. I saw a group of armed soldiers in the windows of the National Bank building next door to the eembassy, just across the narrow alley where embassy vehicles parked. The RSO and I quickly warned the ambassador there was going to be violence very close to the embassy. The RSO suggested that he call all of the reduced staff into the interior hallway adjacent to his office because there were no windows that might admit stray bullets.

While the RSO set about getting all of the Burmese and American staff into the protected upstairs hallway, I went downstairs to the front door and told the marine guards to go to high alert and prepare to seal the front doors quickly. The wide embassy glass double door had an electric rolling steel grate that marines or guards could lower quickly for protection. A lot of civilians were passing on the sidewalks in front of the embassy. I told the RSO, who had joined me at the front door, that we had to help the people outside, who would have no warning about what we expected to happen.

The RSO and I went outside onto the sidewalk under the eembassy portico and ordered all of our drivers and Burmese security guards into the building and began urging the many Burmese passers-by to come inside quickly. We startled them, but with the help of our bilingual guards and drivers, they grasped the threat and hastened up the steps into the narrow entrance foyer inside the front door. I estimate we had 30 to 40 Burmese civilians crowded inside, including at least one Buddhist monk and many young students, when the doors closed and the security grate rolled down.

The RSO stayed downstairs with the Marine Security Guards to keep the guests calm. I ran upstairs and opened the front windows above the outside portico and shouted to a group of people across the street to run or take cover because there was going to be shooting. Sadly, not all of them got away. As the formation of army soldiers approached closer on Sule Pagoda Road, the soldiers inside the National Bank opened fire on the civilians across the street from the eembassy. Those poor people never had a chance, they were either killed or wounded by rifle fire.

Now the Embassy was sheltering several dozen Burmese who would certainly have been shot had they not come inside. They were terrified at what had just happened. We could not in good conscience put those people out on the street with trigger-happy soldiers next door and nearby. Staff took them downstairs to the cafeteria, gave everyone a bottle of water, and calmed them down. After waiting at least an hour the marines opened the alley-side loading door and our drivers bravely went outside and brought two eembassy mini-vans right up to the door to block the view from the soldiers inside the National Bank across the alley. The marines escorted the Burmese into the vans and the drivers took them a dozen blocks away and dropped them off in an area where there were no soldiers. It took several trips to empty the embassy of those frightened people.

It had been a long, tiring, and discouraging day. All over the city another outbreak of brutal repression occurred, and from 18 to 20 September we estimated that the regime had killed more than 3,000 people in Rangoon and more thousands around the country. We were relieved that we had evacuated most embassy staff and all family members to Bangkok just a week earlier.

After more than a week of violence, at the end of September the situation returned to "new normal" in Rangoon. Everyone got accustomed to the new situation: army and police security patrols guarded major intersections, roving truck-loads of armed soldiers moved throughout the city, other trucks with loudspeakers drove around the city broadcasting instructions to be quiet, behave, obey the curfew, and repeated the prohibition of large gatherings. This armed military presence was to last most of the remainder of my assignment in Rangoon.

When a sense of calm returned to Rangoon, everyone was delighted when the State Department agreed that emergency conditions had ended, and the evacuees returned to Rangoon in November.

Lessons Learned During This Critical Period

1. U.S. military personnel, especially FAOs, should familiarize themselves with their Embassy Emergency Action Plan (EAP). If the embassy has not exercised its EAP recently, strongly recommend that take place. U.S. Embassy Rangoon exercised its EAP several months before the events described took place; which provided an invaluable rehearsal for when the real emergency arrived. Ensure that a senior U.S. military officer represents DoDis on the Emergency Action Committee (EAC). Always plan several options.

2. DAO Rangoon and Marine Security Guard personnel knew how to work together in a high-pressure situation. As military personnel we used our training and experience to act quickly, properly, and to make good decisions rapidly. The aambassador and eembassy staff automatically looked to us for leadership in this difficult period of tension and danger.

3. All DAO personnel had routinely used our individual "people watcher" talents and over time had evaluated the staff in our embassy and in the other embassies in Rangoon. We knew who would be of reliable assistance in an emergency.

4. Weeks of violence and tension in Rangoon had prepared us for action. Still, we were surprised at how quickly the crises developed. Be prepared!

5. Despite tension and pressure, all DAO personnel maintained professional, correct relations with the host-country military, no matter the circumstances or the egregiousness of their conduct.

A Final Word

I am very proud of the work of USDAO Rangoon and Marine Security Guard Detachment personnel. If not formally designated as such, all had outstanding FAO-like backgrounds or overseas embassy experience. We knew how to work with other countries' cultures and people. We were highly respected by our diplomatic corps colleagues because of our military bearing and leadership qualities. DAO Rangoon did our best over months of pressure, violence, tension, and threats to security. The ambassador looked to us to reinforce his leadership role and to deal with the host-country military. We provided up-to-date reporting to Washington and to PACOM, and shared our knowledge with diplomatic corps colleagues.

In March 1990 DAO Rangoon received the U.S. Defense Meritorious Unit Award, citing reporting and community leadership throughout an extended emergency period. It was a proud moment for all of us. The U.S. Marine Corps Security Guard Detachment Rangoon was awarded the Navy Meritorious Unit Award. All Rangoon DAO and Marine Security Guard Detachment personnel were awarded the Humanitarian Service Medal.

About the Author

Colonel John B. Haseman (U.S. Army-Retired), Military Intelligence Branch, served as SDO/DATT in Rangoon, Burma, from April 1987 through July 1990. His other overseas FAO assignments included IMET Program Manager and then Army Division Chief, U.S. Defense Liaison Group Jakarta, Indonesia (1978-1981); Assistant Army Attaché Jakarta (1982-1985); and SDO/DATT Jakarta, (1990-1994). Prior to becoming a FAO he deployed twice to the Republic of Vietnam (1967-1968, and 1971-1973). He retired 31 January 1995.

His awards and decorations include the Combat Infantryman Badge; Defense Superior Service Medal (2); Legion of Merit (2); Bronze Star (service)(3); Defense Meritorious Service Medal; Army Meritorious Service Medal; Air Medal (2); Joint Service Commendation Medal; Army Commendation Medal (4); National Defense Service Medal (2); Vietnam Service Medal with 8 service stars; Humanitarian Service Medal (2); Armed Forces Reserve Medal; Army Service Ribbon; Overseas Service Medal (6); Republic of Vietnam Cross of Gallantry (service); Republic of Vietnam Cross of Gallantry with Bronze Star (valor); Republic of Vietnam Honor Service Medal (2); Republic of Vietnam National Police Field Force Honor Service Medal, and Republic of Indonesia Bintang Yudha Dharma Nararya Medal.

A prolific writer, Colonel Haseman has authored or co-authored five books and over 250 published journal articles in the U.S., Asia, Australia, and Europe. The Defense Intelligence Agency inducted Colonel Haseman into the Defense Attaché Service Hall of Fame in 2011.