Casting a Wide Net: Mobilizing Regional Cooperation in the South China Sea

By Major Pablo Valerin, U.S. Army;

Major Natalie Chounet, U.S. Air Force;

Lieutenant Commander Jonathan Smith, U.S. Navy;

and Major Kostyantyn Kotov, U.S. Army

Editor's Note: This article won the FAO Association writing award at the Joint and Combined Warfighting School, Joint Forces Staff College The Journal is pleased to bring you this outstanding scholarship.

Disclaimer: The contents of this submission reflect our writing team’s original views and are not necessarily endorsed by the Joint Forces Staff College or the Department of Defense.

Expanding Chinese territorial ambitions in the South China Sea contests international laws and norms while denying free access to lucrative fisheries in international waters. The U.S. policy response of conducting Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) fails to deter aggressive Chinese behavior given mounting harassment of Southeast Asian fishermen by Chinese vessels. In 2018, a Chinese coast guard vessel rammed a Vietnamese fishing boat in international waters that resulted in ten fishermen falling overboard. Months later, close to fifty ships from the Chinese maritime militia blocked access to fisheries near the Scarborough Reef. Chinese harassment in international waters increases the likelihood of military escalation and destabilizes regional food security. Consequently, the inability of the United States to deter Chinese behavior and uphold international norms risks relinquishing its leadership in the region. Additionally, allies and partners, sensing American acquiescence, are likely to respond by hedging towards China. The United States can effectively address the impasse by taking the lead on developing an initiative centered around cooperation. The codification of an internationally sanctioned, multinational patrolled fishery in the South China Sea will refute Chinese maritime territorial claims, strengthen U.S. partners and allies through improved interoperability, and reduce the risk for future military escalations.

The scope of this paper will discuss the needs, benefits, and implementation of a multinational patrolled fishery in the South China Sea. It will begin by critiquing the existing strategy and how the current regional framework fails to protect fishing rights. Secondly, it will highlight the importance of food security in the region and argue that such a proposal is in the interests of China and Southeast Asian nations. The paper will subsequently outline implementation steps given varying degrees of Chinese participation. Lastly, it will acknowledge gaps and outline policies to mitigate risks. It is important to emphasize that the scope of this paper will not address other contested issues such as Chinese territorial claims or militarization efforts in the area. Holistically, it provides an entry point for introducing all elements of U.S. national power to protect fishing rights in international waters while enhancing regional cooperation. A durable solution can lead to broader future successes regarding more contentious issues.

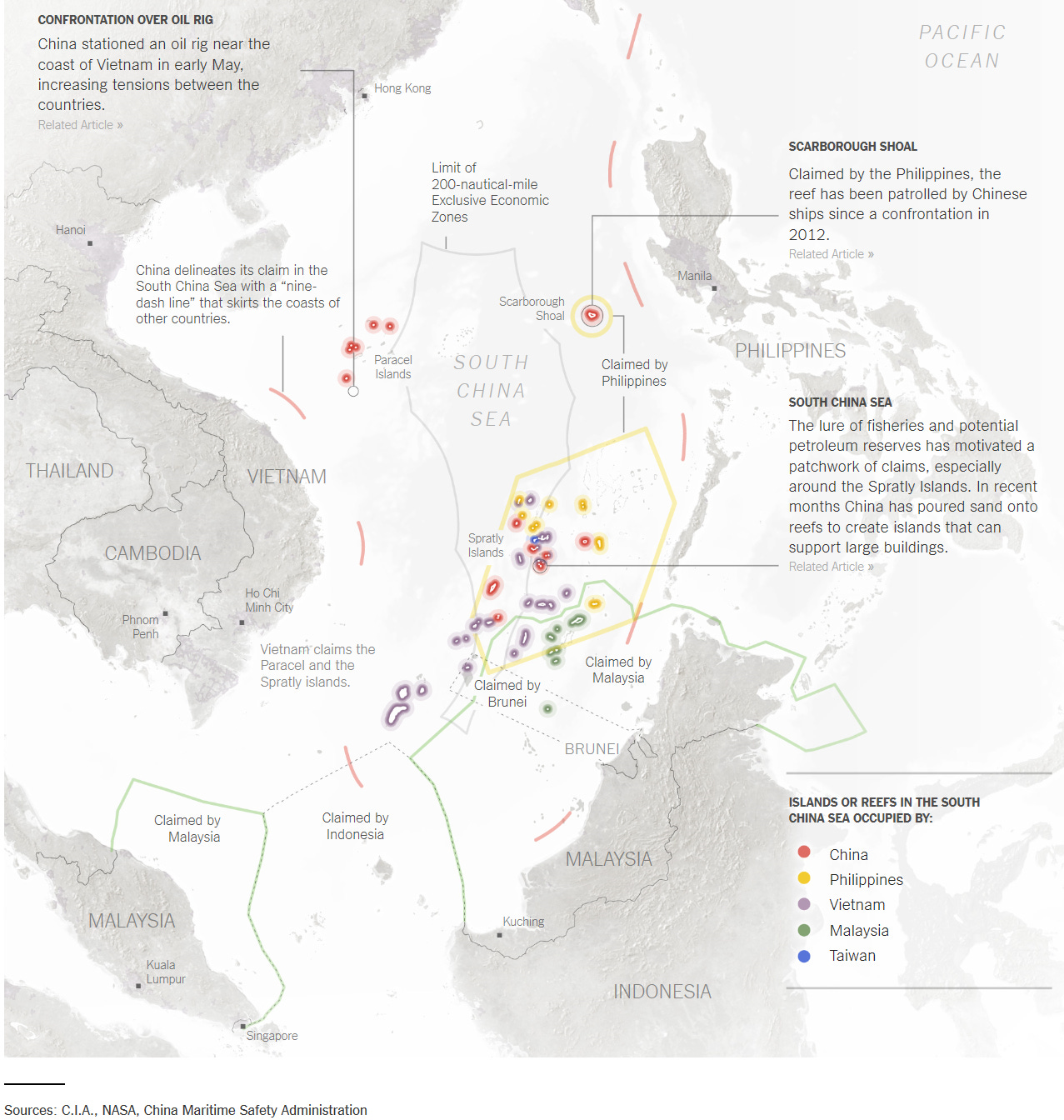

Disputed Claims in the South China Sea

Looking Beyond FONOPs:

U.S. FONOPs intend to uphold the rules-based international order of unfettered access to a free and open South China Sea. However, according to Admiral Davidson, Commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, Beijing ignored the 2016 ruling of an Arbitral Tribunal established under Annex VII of the Law of the Sea Convention (UNCLOS), which concluded that China’s claims to maritime areas of the South China Sea, encompassed by the nine-dash line, are without legal effect. FONOPs contest false Chinese territorial claims but do little to deter the harassment of Southeast Asian fishermen. Chinese Coast Guard vessels regularly harass and intimidate fishing vessels from the Philippines, operating near Scarborough Reef, and fishing fleets of other regional nations. Pursuing a military-only solution that yields few strategic gains is unlikely to deter unabated Chinese behavior or assuage allies and partners from the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN).

ASEAN is constrained by its founding “consensus principle” to stand up to Chinese aggression in the South China Sea. In 2016, ASEAN failed to sign a joint statement that affirmed the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) that ruled in favor of the Philippines’ maritime disputes. China employed economic leverage over Cambodia to effectively block any mention of the court ruling in the joint statement. The threat of Chinese economic coercion also serves as an obstacle to ASEAN signing a code of conduct that would manage South China Sea disputes and protect access to lucrative natural resources. ASEAN’s inability to create a unified front to enforce international laws requires U.S. leadership to coalesce all stakeholders around an innovative approach that provides mutual gains.

Garnering Participants:

The introduction of multinational enforcement mechanisms that protect fish stocks in the South China Sea serves to stabilize the region and provide benefits to ASEAN nations, China, and the United States. Regional risks to trade and food security are the cornerstone of how the multinational fishery initiative will enhance development and security. Chinese participation in the initiative supports their geostrategic ambitions and bolsters their panoply of soft power policies. Their refusal to participate would be counterproductive to their national interests since it risks Chinese diplomatic isolation while enhancing U.S. influence. Additionally, a destabilized South China Sea poses risks to the Chinese Communist Party’s desire for uninterrupted economic growth and stability.

For centuries, the South China Sea served as a major artery for international trade that connects local economies with the broader global network. Both ASEAN nations and China are reliant on the waterway. The economies of ASEAN nations are heavily dependent on maintaining an open and secure area since nearly 70% of their trade transits the strategic sea lanes. Despite Chinese efforts to diversify its global trade delivery systems, it remains reliant on trade through the South China Sea. A stable region where parties can work cooperatively lends itself to future economic prosperity for all stakeholders. Of particular note, the multinational fishery initiative contributes directly to protecting a strategically vital fish stock. The initiative addresses the shared dependency on fish stocks and garners “strategic trust” among stakeholders, which can lead to future negotiations that enhance regional economic stability. The fishery can serve as an initial model for multinational management of disputed natural resources. Existing international and ASEAN frameworks give credence to leveraging cooperation in developing a multinational initiative.

An internationally recognized approach to address the growing food security concern is supported by UNCLOS, which states claimants should use cooperation to adjudicate semi-closed sea resources. Furthermore, ASEAN’s principle of gaining consensus is better suited for addressing shared regional concerns. Such a measure enhances fishermen rights and food security while not aggravating sensitive territorial disputes.

The initiative provides ASEAN with the opportunity to overcome past internal friction by lending itself as a credible organization capable of protecting fishing rights. Indeed, China prefers to leverage its large economy to resolve territorial and resource disputes bilaterally. However, it will be prudent for ASEAN to cajole stakeholders into adopting a multilateral approach given the myriad of claimants in the South China Sea. The creation and enforcement of this initiative will legitimize ASEAN as a credible regional organization and increase interoperability among its militaries and law enforcement agencies. Success in this effort demonstrates that a unified ASEAN is more effective vis-à-vis China when it negotiates multilaterally.

China is likely to join the effort since it particularly stands to benefit from increasing its soft power influence across the region. Since the 1980s, Chinese leaders advocated policies that emphasized shared fishery management and signed the ASEAN-China Free Trade Area agreement in 2002. Chinese participation provides an entry point to cooperate with its neighbors to address illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. China’s soft power influence could directly impact 190 million people that reside in coastal populations while thwarting negative trends in the region. Furthermore, signing on to the fishery effort reinforces Chinese contributions to stabilizing and developing the region. In the short term, Chinese participation allows leaders to assuage neighbor nations and recharacterize “China’s rise” as peaceful and benign. Collectively, Chinese leaders are likely to exchange contested dominance of the South China Sea—with increasing geopolitical costs—for assured diplomatic and economic gains.

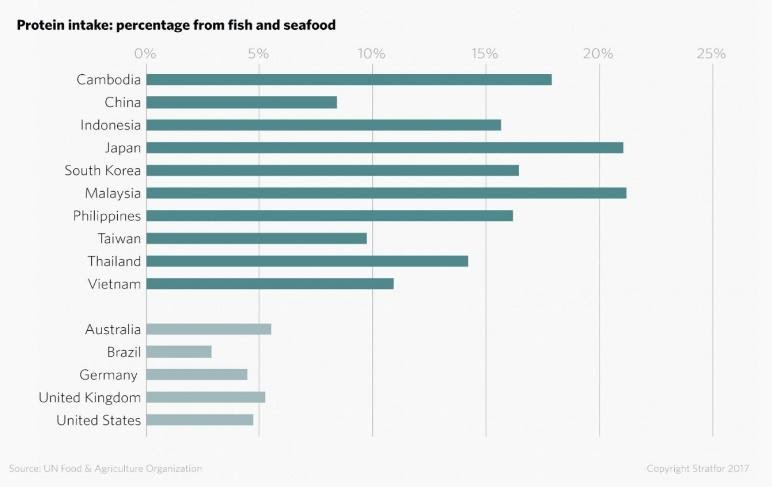

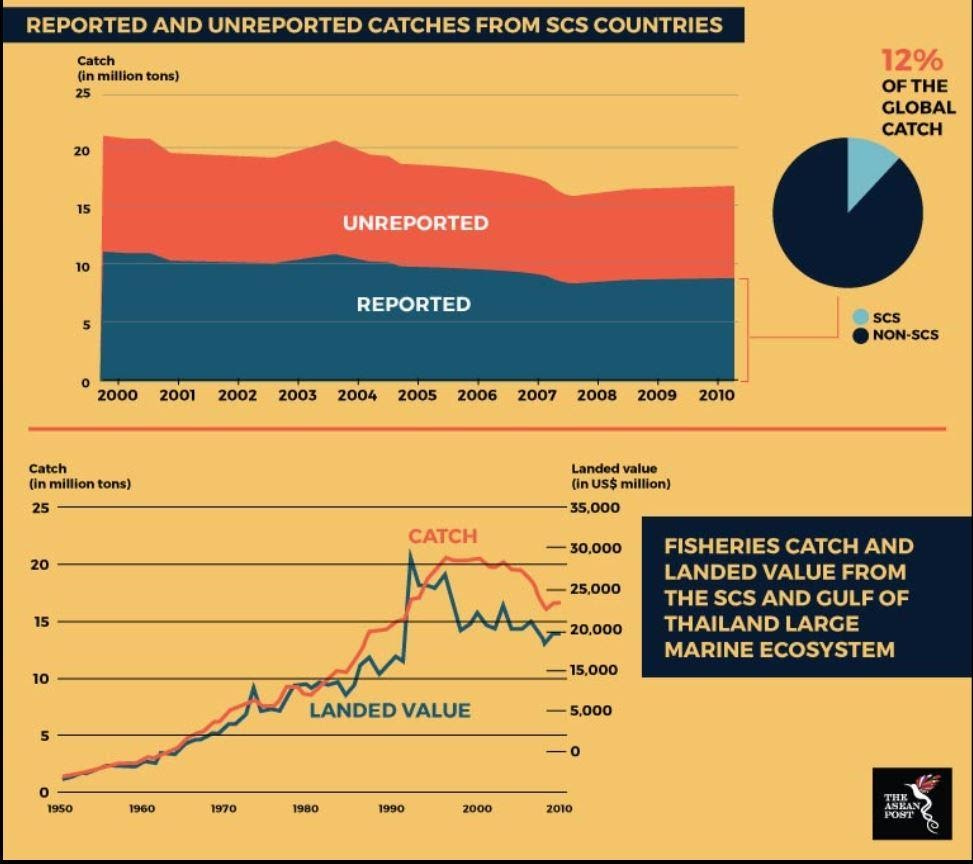

The current lack of fishing regulations in the South China Sea carries far-reaching implications for regional food security and economic development. The multinational fishery initiative will strengthen relationships while providing greater food security as fishing in the South China Sea represents up to 30 percent of the economies of coastal nations. The multinational patrol will provide oversight, increased transparency, and a safer environment for all fisherman. This multifaceted initiative is critical since the demand of ASEAN nations for fish protein is expected to double in the next decade. Additionally, China has food security concerns given their demand for fish proteins increased tenfold in the last 25 years and continues to rise.

Unabated over-exploitation is diminishing fish populations at an unsustainable rate. Improving access to food sources, while ensuring its sustainability across multiple generations, will adequately address food security concerns for all stakeholders. This initiative provides a shared, sustainable solution to marine food demand by providing multilateral enforcement and oversight of fishery management.

De-escalation Through Cooperation:

The implementation of the multinational fishery initiative will necessitate stakeholders to coordinate and cooperatively network law enforcement agencies. The United States will assist with standing up the multinational patrol force by providing training and resources, similar to the Africa Maritime Law Enforcement Partnership (AMLEP) program. The United States can utilize the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard (USCG) to empower partners and provide a credible force posture to enforce maritime fishing laws. This implementation also reemphasizes the assertion that the South China Sea is international water space, which provides precedence to reject claims that a single nation holds preeminence over the entire waterway.

The concept for implementation is manifested in the U.S. national strategic guidance documents that emphasize enhancing U.S. security through investing in partners and allies. To achieve these ends, the U.S. military will undertake a joint mission with the USGC and Navy serving as the lead actors. As seen during AMLEP, the USCG will provide law enforcement training in relation to international fishery laws and provide technical assistance for boarding illicit vessels. The U.S. Navy will build off its success during AMLEP by providing command and control resources and serving as a deterrent against illegal fishing vessels and maritime militias. Another critical resource is providing intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) assets to increase maritime situational awareness and intelligence sharing. Collectively, enhancing training and integration among the law enforcement agencies of all stakeholders increases interoperability and strategic trust.

In addition to training, the United States can strengthen partner capacity and capabilities by expanding security cooperation initiatives. The Fiscal Year 2016 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) created the Southeast Asia Maritime Security Initiative (MSI) which allocated $119 million for building partner readiness, reducing capability gaps, and building capacity. Given the precedence, the United States can leverage the foreign military sales and financing programs to provide ISR assets, communication platforms, and other critical hardware. Additionally, it will be prudent for U.S. policymakers to leverage the Excess Defense Articles (EDA) program to transfer valuable excess military equipment to U.S. partners and allies. In May 2017, the United States transferred a former USCG cutter to Vietnam to improve its maritime domain awareness. Expanding the approach increases partner capacity to perform maritime law enforcement operations while providing strategic messaging of U.S. commitment to cooperation in the South China Sea.

The U.S. interagency will play a critical role in supporting the initiative by providing expertise and additional resources. The U.S. State Department will be the lead agency in building international support around the initiative through a series of U.S. sponsored conferences. Additionally, the U.S. Department of Agriculture can offer policy recommendations for managing existing fisheries and developing sustainability efforts to expand their longevity for future generations. Utilizing all levers of U.S. national power across the diplomatic, information, military, and economic (DIME) spectrum creates unity of effort and additional touchpoints between U.S. policymakers and their respective interlocutors.

Stabilizing the South China Sea and enhancing cooperation among a wide range of stakeholders are a worthwhile return of U.S. investments. Partnerships between the U.S. Navy and members of the initiative does not require a significant commitment of additional assets since it already has an enduring presence in the South China Sea. Another fundamental U.S. interest is creating a network approach of leveraging partners and allies to conduct stabilizing missions independently. In 2016, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia established a trilateral cooperation mechanism to conduct joint maritime patrols of the Sulu Sea to interdict pirates and members of ISIS. The U.S. Navy supported the trilateral by integrating littoral combat ships and frigates to enhance visit, board, search, and seizure (VBSS) techniques and information sharing. The smart application of U.S. security cooperation efforts strengthened the trilateral where it is now able to operate independently and enhance interoperability within ASEAN. The U.S. approach builds off success and creates conditions to foster cooperation with ASEAN and China.

Mitigating Risks:

The bold multinational fishery initiative serves as an evolution to FONOPs since it extends an invitation for the Chinese Coast Guard to participate in the effort. Active participation from China would offer a strong statement of legitimacy in affirming the South China Sea as international waters. On the other hand, China’s refusal to participate signals their tacit approval of the violent tactics used by the Chinese maritime militia against fishing vessels from ASEAN nations. Regardless of China’s ultimate decision, U.S. policymakers will need to develop policies to mitigate risk should China perceive that the initiative crosses a “red line.”

The first approach is to assuage China by claiming that its participation is in their best interests. China’s ultimate strategic goal is achieving President Xi’s “China Dream,” seeing the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation by 2049. To secure this objective, China must endeavor to preserve and uphold its image as a responsible, stable global leader. A rejection of joining the multinational effort that provides mutual benefits will cause the international community to perceive China as the aggressor. The United States previously punished Chinese militarization of the South China Sea by withdrawing an invitation to participate in the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC). U.S. policymakers can cajole Chinese leaders by establishing membership in the fishery initiative as a precondition to participating in future RIMPAC and other potential U.S.-Chinese exercises. Both U.S. and Chinese leaders could claim victory by declaring that the world is more stable when the two strongest nations can cooperate regarding shared interests.

The United States and partners will isolate China diplomatically if Chinese leaders continue to refuse joining the initiative. The initiative will continue as planned and the United States will garner international diplomatic pressure upon China, such that it is boxed in with few good options. The advantages of the approach rest in its dichotomous and anticipatory nature. The overt deployment of U.S. and ASEAN military and law enforcement vessels in the South China Sea will not compromise the U.S. image of a regional stabilizer forged by strategic messaging that promotes protecting fishing rights. Additionally, the United States will call on China to adopt the 2014 Code of Unplanned Encounters at Sea to mitigate escalation scenarios between the multinational patrol and Chinese vessels. The overt U.S. and ASEAN messaging that promote de-escalation thereby frames any armed Chinese response as undeniably aggressive in nature, thus preserving the moral high ground. Furthermore, the United States and its partners will continuously request China to join the initiative to codify full international support and de-escalate tensions.

United States policymakers will additionally need to develop strategies to assuage the concerns of partner nations over Chinese economic coercion for their participation in the multinational effort. In 2017, China employed several economic coercive policies against South Korea over the deployment of a Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile system. Collectively, the sanctions resulted in over $15.6 billion in lost revenue and South Korean leaders eventually relented by declaring the infamous “three nos” - no future deployments of THAAD missile systems, no integration into a U.S. missile defense network, and no membership in a military alliance with the United States and Japan. The United States should recognize that the future economic growth of partner nations is highly dependent on Chinese infrastructure investments.

U.S. policymakers can effectively blunt the impact of Chinese economic coercive strategies by working with Japan to offer ASEAN nations an alternative to Chinese Belt Road Initiative investments. In 2018, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo pledged $113 million in funding for “smart infrastructure.” Meanwhile, Japan announced the ambitious Infrastructure Export

Strategy, which will invest over $270 billion across ASEAN by 2020. When combined, the United States and Japan outspend Chinese foreign investments in South East Asia, which is estimated at $155 billion. The United States can alleviate ASEAN concerns since American and Japanese “smart infrastructure” projects will serve as a foil to opaque Chinese contracts by providing the highest levels of transparency and hiring local workers. Furthermore, Chinese economic coercive strategies will hurt its standing in the international community by unveiling its patron-client model and force leaders from ASEAN nations to make hard choices to diversify their respective economies better.

As previously discussed, the scope of the multinational initiative does not address China’s alarming strategy of militarization the South China Sea. Instead, the multinational approach sets a foundation for increased levels of coordination between the United States, ASEAN nations, and China. The initiative will serve as an important confidence-building measure that demonstrates military and law enforcement cooperation is achievable and stabilizing. Success can eventually lead to the codification of a regional-wide South China Sea Code of Conduct. Additionally, lessons learned can be applied to a more ambitious strategy which calls for the overall demilitarization of the entire South China Sea. The successful codification of a multinational fishery will serve as the foundation of tackling small problems before addressing more complex issues.

Strength Through Cooperation:

The status quo in the South China Sea provides China with a means of eroding the effectiveness of the United States military and calling into question the durability of the international rules-based order regarding a free and open South China Sea. FONOPs fail to yield strategic gains and are more likely to lead to an armed escalation scenario. The codification of an internationally supported multinational fishery sets a precedent of reducing tensions through increased cooperation. The initiative demystifies the false binary choice between aggression or ceding influence. Now is the time for U.S. policymakers to act given China’s rapid modernization efforts and the alarming rate of their militarization of the South China Sea. The United States can leverage its stronger military and economic engine to enlist new partners in the initiative that protects fishing rights in international waters.

This proposal argues that the proper application of policies across the DIME and multinational domains have the potential to reduce tensions and provide mutual benefits for all participants. The initiative affirms U.S. primacy in the region and as the partner of choice for ASEAN nations. U.S. leadership in the multinational approach signals to partners and competitors alike that it has both the hard capabilities and political will to defend the international rules-based order.

About the Authors:

Major Pablo Valerin is Chief of Security Cooperation in Timor-Leste. In 2018, he graduated from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies with a MA in International Public Policy with an affiliation on Strategic Studies. Previously, he led both combat and construction engineer units in Iraq and across the Indo-Pacific AOR.

Major Natalie Chounet is currently assigned as Flight Commander, Operations Flight in the 47th Civil Engineer Squadron, Laughlin AFB, Texas. She earned a BS degree in civil engineering, and an MBA in Project Management in 2014. Prior to her current assignment, Major Chounet served at Pacific Air Forces Headquarters, Hawaii.

Lieutenant Commander Jonathan Smith is a Branch Chief in the Environment Architecture Division at the Joint Staff, J-7, in Suffolk, VA. He earned a BS degree in History from the U.S. Naval Academy and an Inter Master of Professional Studies degree in Homeland Security from Pennsylvania State University. Prior to his current assignment, LCDR Smith served and deployed in multiple HSL/HSM squadrons in San Diego and also served as a Weapons Tactics Instructor at the HSM Weapons School Pacific. He is qualified on the SH-60B and the MH-60R.

Major Kostyantyn Kotov serves as Treaty Compliance Officer, Defense Threat Reduction Agency. He earned a BA degree in Management and Human Resources from Park University in 2006, and an MS degree in Environmental Management from Webster University in 2010 followed by an MA degree in International Public Policy from John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in 2015.

Work Cited

AFRICOM Public Affairs. Africa Maritime Law Enforcement Partnership (AMLEP) Program. (U.S. Army. 2016).

CTF 73 Public Affairs. US-Philippine Navies Complete Coordinated Patrol in Southern Sulu Sea. (U.S. Navy. June 30, 2017).tf

Davidson, Philip. On U.S. Indo-Pacom Command Posture. (Statement Before the Senate Arms Committee. February 12, 2018).c

Erickson, Andrew. Understanding China’s Third Sea Force: The Maritime Militia (Medium, September 8, 2017).

Green, Michael, Kathleen Hicks, and Mark F. Cancian. Asia-Pacific rebalance 2025: Capabilities, presence, and partnerships. (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016).

Gutierrez, Jason. Philippine Official, Fearing War With China, Seeks Review of U.S. Treaty. (The New York Times. March 05, 2019).

Hiebert, Murray. Southeast Asia Financial Integration and Infrastructure Investment (Center for Strategic International Studies, May, 2018).

LaGrone, Sam. Former U.S. Cutter Morgenthau Transferred to Vietnamese Coast Guard. (U.S. Naval Institute News. May 26, 2017).

McGuire, Kristian. China-South Korea Relations: A Delicate Détente (The Diplomat, February, 2018).

Men, Sreypov. Chinese Coast Guard Chases Down, Rams Fleeing Vietnamese Fishing. (ASEAN Economic Community News Today. November 01, 2018).

Nguyen Dang, Thang. Fisheries Co-operation in the South China Sea and the Irrelevance of the Sovereignty Question." (Asian Journal of International Law 2, 2012).

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Building Food Security and Managing Risk in Southeast Asia. (OECD Publishing, 2017).

Panda, Ankit. How Much Trade Transits the South China Sea? Not $5.3 Trillion a Year. (Scientific American, 2017).

Parameswaran, Prashanth. Are Sulu Sea Trilateral Patrols Actually Working? (The Wilson Center. January 29, 2019).

Trump, Donald. National Security Strategy of the United States of America (White House, December 2017).

Wroughton, Lesley. Wary of China’s Rise, Pompeo Announces U.S. Initiatives in Emerging Asia (Reuters, July, 2018).

Yoshimatsu, Hidetaka. Japan's Export of Infrastructure Systems: Pursuing Twin Goals Through Developmental Means (The Pacific Review, No. 4, 2017).

Zhang, Hongzhou. Fisheries Cooperation in the South China Sea: Evaluating the Options. (Marine Policy 89, 2018).