Building Faith and Balancing Fear: Assurance and Deterrence on the Korean Peninsula

By Major Daniel K. Trapani, U.S. Air Force

Photo: USAF B-1s train with Republic of Korea Air Force F-15 Slam Eagles and USAF F-16 Fighting Falcons during bilateral training in airspace above South Korea, Feb. 20, 2025. Photo Courtesy of ROKAF

Editor's Note: Major Trapani's thesis won the Major General Lansdale International Affairs Outstanding Research Award / Foreign Area Officer Association writing award at the U.S. Air Command and Staff College. Because of its length, we publish this version without research notes. To read the full thesis, please contact us at editor@faoa.org. The Journal is pleased to bring you this outstanding scholarship

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government or the Department of Defense. This report contains no information that is classified or controlled unclassified information (CUI). In accordance with Air Force Instruction 51-303, it is not copyrighted, but is the property of the United States government.

Abstract

This paper explores the complexities of nuclear deterrence and assurance in the context of U.S.-South Korea relations amidst growing threats from North Korea and China. Drawing from theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence, the analysis underscores the importance of credibility, both rational and emotional, in shaping perceptions of deterrence and assurance. It highlights the need for unique strategies to achieve deterrence and assurance objectives, balancing the manipulation of fear with building faith among allies. Examining various courses of action (COAs), the paper evaluates their effectiveness based on criteria such as enduring consultation, integrated planning, military presence, balance of fear, and political and economic feasibility. Among the proposed COAs, COA 3 emerges as the most viable option, emphasizing consultation mechanisms, military integration, and strategic messaging to strengthen South Korean faith in U.S. nuclear commitments while minimizing the risk of escalation with regional adversaries. In conclusion, the paper emphasizes the imperative of bolstering assurance with South Korea to prevent nuclear proliferation and maintain regional stability. It underscores the need for nuanced approaches that address the evolving geopolitical landscape in the Pacific, ultimately advocating for strategies that build faith and balance fear on the Korean Peninsula to ensure peace and security in the region.

Introduction

Problem

Today, the United States faces geopolitical challenges across the globe. In the 2022 National Security Strategy, President Biden stated that the U.S. is at an inflection point where autocracies seek to overturn the U.S.-led democratic international order based on the rule of law. Alliances and partnerships remain key to securing U.S. vital interests and preserving democracy. While U.S. alliances have grown stronger in the Western Hemisphere despite Russian aggression, those in the Eastern Hemisphere appear vulnerable. Chiefly, the Republic of Korea (ROK) seems to lack assurance of U.S. resolve to uphold its security commitments. A South Korean public opinion survey conducted in December 2021 revealed that 70% of South Koreans believe that the U.S. should return its nuclear weapons to the ROK or South Koreans should pursue an independent nuclear weapons program. In January 2023, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol stated that if North Korea continues to expand its nuclear arsenal, the ROK may be forced to pursue its own nuclear weapons program or request the U.S. to redeploy its nuclear weapons to the peninsula. Later in 2023, President Biden met with President Yoon and crafted the historic Washington Declaration which underscored the U.S. commitments to the ROK and highlighted the nuclear umbrella. Each of these events illustrate the enduring assurance problem in South Korea. Since 2018, the U.S. has made nuclear arsenal modernization the highest priority in the Department of Defense and reinvigorated its deterrence strategy. Why then is U.S. assurance wavering in the ROK and under what conditions can the U.S. improve assurance to the ROK while maintaining regional strategic stability?

Background

From 1950 to 1953, the United States fought to defend Korean sovereignty against North Korea, China, and the Soviet Union and lost over thirty-six thousand service members in the process. Over the seventy years that followed, the U.S. has shielded the Republic of Korea via a mutual defense treaty which included U.S. extended nuclear deterrence. From 1958 to 1991, the U.S. stationed nuclear weapons on the peninsula to enhance its extended deterrence. At the end of the Cold War in 1991, President George H. W. Bush unilaterally withdrew many U.S. nuclear assets around the globe to encourage similar disarmament from former Soviet states and this included the ROK. In 1985, North Korea signed the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), which prohibited the pursuit and acquisition of nuclear weapons and affirmed this commitment in 1992 by signing the Joint Declaration of Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula with the ROK. Yet as early as 1993, North Korea demonstrated a desire to seek nuclear weapons when President Kim Jong Il threatened to withdraw from the NPT. In 2003, he followed through on this threat by formally withdrawing from the treaty, and successfully tested a nuclear weapon in 2006. Since that time, North Korea has steadily built its nuclear arsenal and delivery systems and today possesses the capability to reach as far as the Continental United States with its Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs). Meanwhile, tensions between North and South Korea have also progressively risen. In March 2010, the South Korean warship, Cheonan, was sunk killing forty-six ROK sailors. Although North Korea claimed innocence, the Republic of Korea held them publicly responsible following the results of a multi-lateral investigation. Later in November of that year, North Korea fired multiple salvos of artillery onto Yeonpyeong, a South Korean Island, killing four people. In January 2024, this shelling was repeated by North Korea, although no casualties were recorded on the island. The last thirty years of North Korean belligerence and nuclear development has taken its toll on the ROK and today many South Koreans desire nuclear weapons back on their soil to ensure ROK national security.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) further complicates South Korean security. PRC expansion in the South China Sea and increasing aggression against Taiwan demonstrates its intent to coerce its neighbors to achieve strategic ends. The PRC has executed a peacetime military build-up at a rate not seen since Germany prior to World War II, and is projected to match U.S. conventional (non-nuclear) capability by 2030. Additionally, the PRC has expanded its nuclear capabilities to attain a nuclear triad and continues to increase its nuclear stockpile at an alarming rate. As a historical North Korean ally and one of its only global partners, the PRC poses a threat to the ROK as well as regional stability.

The growing threat of nuclear conflict challenges the United States. As a nuclear weapon-possessing signatory of the NPT, the U.S. has committed to moving toward a world free of nuclear weapons and nuclear non-proliferation has remained an enduring foreign policy priority for every U.S. president in the 21st Century. The U.S. nuclear umbrella plays an important role in nuclear non-proliferation as a U.S. extended deterrence commitment allows participating nations to forgo an indigenous nuclear program and remain protected from existential attack. If a participating country believes the U.S. may not follow-through on its commitments, that country may pursue a nuclear program. Such action would jeopardize its alliance with the U.S. and could cause other nations to acquire nuclear weapons as well. In order to prevent nuclear proliferation and preserve its alliances, the U.S. must rethink its strategy regarding assurance.

Theory

This paper argues that while effective nuclear deterrence and assurance on the Korean Peninsula both hinge on the United States’ credibility, allies and adversaries perceive U.S. credibility differently; therefore, actions to bolster deterrence do not have the same impact on assurance and vice versa. Whereas successful deterrence creates fear in the mind of an adversary, successful assurance creates faith in an ally. This stark emotional difference means that a deterrence strategy does not transfer directly to one of assurance. Thus far, the U.S. has deterred any strategic attack against the ROK and its deterrence credibility has remained relatively unchanged. So why do 70% of South Koreans believe they either need U.S. nuclear weapons on their homeland or to pursue an indigenous nuclear weapons program to feel secured? In her 2021 article in the Washington Quarterly Journal, Lauren Sukin stated, “…the acute credibility problem is not about nuclear capability, but it instead reflects concerns about the durability of U.S. political commitments.” Through nuclear modernization and tailored deterrence strategies, the U.S. has maintained its deterrence credibility against South Korea’s existential threats, but it has neglected to grow assurance credibility within the ROK itself. As a result, North Korea fears U.S. retaliation, but polling data, statements from ROK President Yoon, and the Washington Declaration show that South Korea is losing faith in U.S. commitment. To preserve its alliance and prevent nuclear proliferation, the U.S. must employ a strategy which builds South Korean faith in the U.S. promise of protection without sacrificing stable strategic deterrence with either North Korea or China.

Four deterrence concepts form the foundation for this theoretical argument. First, credibility is best determined using the current calculus model developed by Daryl Press for both deterrence and assurance. The current calculus model holds that credibility is based on an actor’s power and interests at stake rather than their reputation for fulfilling threats or commitments in the past. Second, deterrence and assurance credibility is further refined through an emotional lens based on the recipient’s perspective. For adversaries, deterrence credibility translates to a manipulation of fear. For allies, assurance becomes a function of faith. Third, as one state increases its security, or the security of an ally, other states fear for their own security because they cannot trust that their opponent is increasing its security for defensive-only purposes. This security dilemma can lead to a spiral of fear where each side unyieldingly increases their security to counter the other ultimately resulting in a failure of deterrence. This is a critical concept to consider because U.S. actions to improve ROK assurance, such as deploying nuclear weapons to the Korean peninsula, could result in just such a situation. Finally, nuclear non-proliferation remains not only in the United States’ best interest but also that of South Korea. While conventional wisdom contends that a nuclear-armed South Korea could better deter aggressors than the U.S. through extended deterrence, some theorists argue that until a new nuclear power experiences the fear of reaching the brink of nuclear war, they will execute dangerously assertive foreign policies. Based on the highly volatile nature of the North-South Korean relationship, it is possible that these two nascent nuclear powers might cross the nuclear threshold as each tries to dominate the other through nuclear coercion.

Theory

Nuclear reactors are capable of rational thought and impacted by emotional feelings. Credibility is therefore a function of both rational calculations, judging a nation’s power and interest, and emotional feeling based on human interaction. Because credibility exists only as a perception, it is susceptible to error based on one’s rationality bounds as well as their emotions. Although judging an actor’s current credibility on past actions is often inaccurate because of the myriad of differing variables, a past action’s emotional impact can influence one’s perception of credibility even in the face of rational evidence to the contrary. For deterrence, nuclear actors must well establish their power and interest, but also balance an opponent’s fears. Too much fear creates a security dilemma which could ultimately spiral into deterrence failure. Too little fear and an opponent is undeterred. For assurance, a nuclear patron must instead build faith in their ally. Because deterrence and assurance seek to achieve different objectives, fear and faith respectively, the United States must develop unique strategies focused on deterrence and assurance. While the United States’ nuclear deterrence strategy has succeeded from preventing existential attacks on itself or its allies, the U.S. has neglected to develop a comprehensive assurance strategy for its allies in India-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) and specifically the ROK. Therefore, the U.S. must take action to build South Korean faith in the U.S. nuclear umbrella but do so without unbalancing the deterrent fear of its two regional adversaries, China and North Korea.

Deterrence Against North Korea Is Still Strong

Although the United States must modernize its nuclear forces to maintain its competitive edge in the 21st Century, it currently possesses the nuclear capability to follow through on deterrent threats around the globe. In his February 2024 testimony to the Senate Armed Service Committee, General Cotton, Commander of U.S. Strategic Command, stated, “Let me be clear: while modernization will continue to be the priority, U.S.STRATCOM forces are ready to fight tonight.” When measuring power as a factor of deterrence, Daryl Press argues that if an actor perceives an opponent has enough power to achieve their objectives at reasonable cost, then their power factor is strong. Viewed through this lens, the U.S. power factor remains unchanged for deterring existential threats to South Korea. North Korean acquisition of nuclear weapons and intercontinental ballistic missiles has not substantially limited the U.S. from following through on its deterrent threats. Furthermore, U.S. anti-ballistic missile systems greatly reduce the likelihood of a successful North Korean nuclear strike on the U.S. homeland.

In regard to the interest factor, the U.S. has continuously messaged its stance to defend South Korea, most recently in the 2023 Washington Declaration. The ROK also hosts nearly twenty-five thousand U.S. servicemembers which act as both a conventional deterrent and a clear “trip wire.” If North Korea strikes into South Korea with either conventional or nuclear weapons, it risks U.S. retaliation. Although North Korea has not stayed dormant, the sinking of the Cheonan and shelling of Yeonpyeong Island in 2010 as extreme examples, their operations remain in the grey zone of military conflict, the zone short of conventional military-to-military war. These activities are reflective of the stability-instability paradox which contends that the more stable two or more nations are at the upper end of conflict, nuclear and conventional, the more likely instability will exist at the lower end of conflict. In other words, because North Korea has no mechanism to coerce the ROK using conventional or nuclear power, it is forced to use other methods. Such actions demonstrate that the U.S. deterrence strategy is working against North Korea. While nuclear assurance credibility may require growth in U.S. power and interest, those increases may negatively affect deterrence by triggering a spiral of fear which leads to nuclear employment. To deter North Korea from pursuing nuclear assertion, the U.S. must present a unified front with the ROK and uphold its deterrence credibility while also balancing North Korean fears which could lead to preemptive war.

Why South Koreans Are Losing Faith

One of President Ronald Reagan’s most famous slogans was “trust but verify.” Although President Reagan used this phrase in reference to an opponent’s promises, it encapsulates what is lacking within the U.S. nuclear promises to the ROK and strikes at the heart of why South Koreans are losing faith. The lack of verification impacts South Korean’s perception of U.S. credibility in terms of both power and interest, and ignites long-held fears of U.S. abandonment.

First, the U.S. has not established an institutionalized means of nuclear consultation between U.S. and ROK decision-makers. U.S. strategic ambiguity leaves South Koreans in the dark regarding the U.S. commitment’s content and scope. As a result, South Koreans perceive the U.S. is not taking action to counter North Korean advances is in nuclear technology and capability. In the last three years, the U.S. shifted deterrence policy from a nuclear focus to an integrated deterrence concept which encompasses the whole of government. In the face of increasing North Korean nuclear capability and belligerence, South Koreans may perceive this U.S. policy shift as a signal of decreasing U.S. interest to follow through on its nuclear security promises. A perceived U.S. de-emphasis on nuclear deterrence in favor of less escalatory measures likely contribute to South Korean fears that the U.S. will fail to follow-through on its security commitments to the ROK.60 As Brad Roberts stated in The Case for U.S. Nuclear Weapons in the 21st Century, “…further reductions in the role and number of nuclear weapons are troubling to allies who count on credible extended deterrence…Washington must remain attentive to these views as it tries to shape them in a manner consistent with its own.” Public declarations like the 2023 Washington Declaration are important to communicate the U.S. interest component of nuclear credibility, but to truly build faith the U.S. must establish an enduring consultation mechanism.

Second, the U.S. has not integrated the ROK into a bi-lateral nuclear planning and execution framework. The U.S. has not directly incorporated the ROK into the nuclear execution mission as it has with NATO countries. Although the ROK does not possess nuclear capabilities, its non-nuclear forces could assist in conventional support to nuclear operations (CSNO). Because the ROK military is not incorporated into the nuclear mission in any way, South Koreans feel more like a tool and less like a partner of the U.S.. These emotions hamper U.S. assurance credibility. Introducing new capabilities to the peninsula will bolster credibility’s power component for both assurance and deterrence in the short term, but the U.S. must integrate the ROK military into nuclear planning and execution to strengthen its credibility in perpetuity.

Finally, South Koreans have lived in fear of subjugation since Japan’s invasion of the Korean peninsula in 1910. It was the U.S. who liberated South Korea during WWII and it was the U.S.-led coalition that stopped the communist invasion in 1950. Today, the U.S. security alliance is as critical to South Korean freedom as it was in 1953. While this shared history formed one of the strongest U.S. alliances in the Pacific, South Koreans also fear U.S. abandonment. South Koreans remember President Nixon’s troop withdrawals in 1971 which triggered South Korean President Park to begin a nuclear program. It was only after a threat to withdraw all troops that the program was canceled. These fears resurfaced in 2019 when President Trump threatened to withdraw troops if the ROK did not contribute more to offset sustainment costs. For many South Koreans, a U.S. troop reduction or withdrawal would signal weak resolve to defend the ROK from an existential North Korean attack.

What “Right” Looks Like

To uphold its alliance, prevent nuclear proliferation, and preserve regional stability, the U.S. must first divorce itself from the idea that deterrence credibility equals assurance credibility and as such develop a strategy which addresses both. Second, as the literature review outlined, the U.S. must establish a means of enduring consultation with the ROK. Public declarations of commitment are valuable, but South Koreans must have a formal and lasting means of influencing U.S. deterrence strategy in their region to feel assured. Third, the U.S. must create a mechanism to involve the ROK military in the operational planning and execution of the nuclear mission. Such action would build immense trust within the alliance which is integral to cultivating assurance. Fourth, U.S. military basing on the Korean Peninsula is critical to demonstrating U.S. interests at stake which boosts both deterrence and assurance credibility. Lauren Sukin cited persistent U.S. presence as the most essential method to prove U.S. commitment to the ROK. Finally, the U.S. must execute a deterrence strategy which produces enough fear to prevent an adversary from striking U.S. and allied vital interests without placing that adversary in a security dilemma which could lead to deterrence failure. While this is difficult to accurately predict, any U.S. action which dramatically increases its nuclear capabilities in the region will likely place both China and North Korea in a security dilemma.

Courses of Action

Based on the theory detailed in Chapter 3, each COA presented in this chapter will be evaluated on the following criteria.

Enduring ROK Consultation: Chapters 2 and 3 clearly establish the importance of consultation in building faith within allies. While constant consultation is difficult to maintain, establishing consistent and enduring consultation mechanisms is essential to building faith within the ROK long-term. Therefore, this category is weighted to reflect that.

Integrated Planning & Execution: Similar to consultation, integrating allies into nuclear mission sets is vital to establishing mutual trust and long-term faith in U.S. nuclear patronage which Chapters 2 and 3 support. Therefore, this category is likewise weighted.

U.S. Military Presence: While continuous U.S. military presence is a critical factor for preserving assurance, increasing the strength of that presence eventually has diminishing returns. Additionally, as Chapter 2 annotated, enduring consultation and nuclear integration add more long-term assurance value than U.S. military presence. Therefore, this category is not weighted.

Balance of Fear: As described in Chapter 2, successful deterrence is the manipulation of fear and determining the appropriate balance between generating too little and too much fear in an opponent. This balance is key to achieving a stable deterrence relationship. Any COA which fails to achieve this balance is unsuitable. Therefore, this category is weighted.

U.S. Political Acceptability: A suitable COA will be one that is estimated to be politically acceptable to U.S. decision-makers. This estimate is based on the current presidential administration’s strategic guidance and under present geopolitical conditions. This category is not weighted because political sentiment and executive guidance can change rapidly.

ROK Political Acceptability: Although similar to category 5, this category is more representative of South Korean sentiment regarding U.S. commitment as a whole. Intent is to capture how well the COA addresses specific and perceived concerns ROK leadership have regarding U.S. assurance and U.S. capabilities. This category is not weighted because political sentiment is difficult to calculate and can change rapidly.

U.S. Economic Feasibility: Although nuclear triad modernization has the highest fiscal priorities for the DoD, the U.S. Congress may not accept further nuclear investment. All three legs of the nuclear triad are currently in upgrade as well as assets performing nuclear command and control and nuclear security. A successful COA is one that assures allies and deters adversaries without extensive impact to the DoD budget. Because strategic stability is essential to U.S. national security, although the economic impact is important, is not weighted.

COA 1

On 26 April 2023, U.S. President Biden and ROK President Yoon Suk Yeol signed the Washington Declaration which publicly reaffirmed the U.S.-ROK alliance and the U.S. nuclear security guarantee. Apart from acting as a recommitment to the alliance, the Washington Declaration established the Nuclear Consultative Group (NCG) to act as a nuclear consultation and planning mechanism to manage the threat posed by North Korea. Since April 2023, the NCG has met on three occasions to outline the group’s role, responsibilities and functions. Three months later, the U.S. made a port call with a nuclear-armed ballistic submarine to the South Korean port city of Busan. This visit marked the first time in decades that the U.S. brought nuclear weapons within ROK sovereign territory. This visit was followed by a non-nuclear ballistic missile submarine port call later in July. In October, the U.S. deployed a nuclear-capable B-52H Stratofortress bomber to the peninsula to participate in an exercise and air show, another historic event. Finally, the U.S. sent another non-nuclear ballistic missile submarine to the port of Busan in December 2023. Deploying these nuclear capabilities in such a manner does not add any military value. On the contrary, highlighting a submarine’s location actually detracts from its military effectiveness. Instead, these demonstrations chiefly serve as public declarations of nuclear assurance to the ROK.

Under COA 1, the U.S. will build faith by continuing to develop the NCG to reach a level of consultation equivalent to that demonstrated in NATO. Furthermore, the NCG will seek to expand into nuclear planning operations between the U.S. and ROK and integrate the ROK military into U.S. CSNO execution plans. Integrated deterrence will remain the overall U.S. deterrence strategy and dominate diplomatic vernacular in both domestic and international forums. Although the U.S. will continue to modernize its nuclear triad, it will not pursue new nuclear capabilities such as Surfaced Launched Cruise Missiles-Nuclear (SLCM-N), nuclear-capable hypersonic missiles, or ground-based Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missiles (IRBMs). Furthermore, the U.S. will boost the perception of U.S. military presence on the Korean Peninsula through public displays of commitment similar to the B-52 and nuclear ballistic missile submarine visits to the ROK. COA 1’s goal is to build faith with the ROK primarily through consultation, public diplomacy, and recurring public affirmation while continuing to emphasize integrated deterrence’s wholistic approach.

COA 2

In this COA, the U.S. reverts its deterrence focus entirely back to nuclear weapons and ultimately deploys nuclear weapons back to the Korean Peninsula indefinitely. Although the NCG perpetuates as a consultation mechanism, the U.S. de-emphasizes ROK integration into nuclear planning and execution. U.S. and ROK decision-makers collaborate, but South Koreans are only minimally integrated into CSNO planning and execution and military-to-military information sharing regarding operational nuclear plans remains low. Instead of integration, the emphasis shifts to a U.S.-centric, capabilities-based response with U.S. nuclear weapons inside the ROK. With this strategy, the U.S. deploys its own Dual-Capable Aircraft (DCA) F-35 squadron, certified to drop conventional and nuclear weapons, to South Korea and constructs a weapons storage facility to house the B-61 nuclear weapons on the Korean Peninsula. Furthermore, given that the United States withdrew from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty on 2 August 2019, the U.S. develops and fields an Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missile (IRBM) to the ROK. Although the U.S. directs its strategic messaging for this deployment of nuclear assets at North Korea, these nuclear assets are designed to increase the U.S. theater nuclear deterrence against China as well. COA 2’s goal is to reestablish faith in U.S. security commitments by giving South Koreans what they asked for: U.S. nuclear capabilities in their homeland.

COA 3

In this COA, the U.S. empowers South Koreans to fully participate in the extended nuclear deterrence process through diplomatic, information, and military avenues without deploying U.S. nuclear weapons to the Korean Peninsula. COA 3 emphasizes nuclear deterrence over integrated deterrence, but utilizes the diplomatic, informational, military, and economic spheres to bolster faith in the nuclear umbrella. In the diplomatic sphere, the NCG builds upon its Washington Declaration mandate by meeting regularly and setting bi-lateral nuclear policy objectives. Additionally, the U.S. performs exchange diplomacy with ROK military members to facilitate deliberate nuclear deterrence and assurance education regarding decision-making and strategy. The U.S. Air Force School of Advanced Nuclear Deterrence Studies (SANDS) located at Maxwell AFB, Alabama is one such avenue for nuclear exchange diplomacy. Within the information sphere, the U.S. will follow through on the Washington Declaration of 2023 to facilitate bi-lateral nuclear response planning and CSNO integration. In the military sphere, the U.S. works with the ROK military to produce one or more Korean F-35 squadrons which are DCA certified. The U.S. must store the B-61 nuclear bombs on either a U.S. territory or on a new U.S. base in northern Australia. Finally, the U.S. facilitates discounted foreign military sales to the ROK to enable rapid South Korean acquisition of nuclear-certified F-35s.

COA Analysis

COA 1 establishes a strong consultation mechanism through the NCG which is similar in spirit to the Nuclear Planning Group within NATO. After publishing the Washington Declaration, the U.S. has followed through on its promise to establish the NCG and outline its roles and responsibilities. However, this initiative is only worth the word of the current president, and a new U.S. presidential administration in 2025 could drastically impact their future. COA 1 succeeds in integrating the ROK into U.S. nuclear planning through information sharing, and incorporating the ROK military into CSNO execution plans through bi-lateral training. Generally speaking, the CSNO mission set is an essential aspect of nuclear operations planning, but South Koreans have long desired the level of nuclear partnership experienced in NATO where allied partners train to execute the nuclear mission itself. Although CSNO integration is a step in the right direction, it is not enough to build South Korean faith long term. The increased U.S. public security commitment displays demonstrated by the B-52 and submarines does improve the perception of U.S. military presence in South Korea, but these demonstrations also have several drawbacks. First, such exhibitions demonstrate U.S. commitment because they are a novelty. If they become commonplace, South Koreans may quickly discount them. Additionally, as other situations arise across the globe, these displays may dwindle, resulting in a perceived lapse in U.S. commitment. While these demonstrations do bring U.S. nuclear capabilities into the Korean limelight, such action is not likely to increase the deterrent fear on North Korea’s part as they do not increase military effectiveness. U.S. nuclear retaliation is likely neither more nor less credible from the North Korean perspective. Although U.S. politicians are likely to well-receive COA 1, the ROK polity may deem it a weak response. For South Koreans, the threat is chiefly nuclear, and the current administration’s integrated deterrence strategy inherently minimizes its nuclear deterrence message by grouping it with other foreign policy tools. Finally, as the U.S. will not expand nuclear capabilities beyond triad modernization, COA 1’s economic viability rates well.

COA 2’s focus on returning nuclear weapons to the Korean Peninsula centers on a political shift in The White House as such action differs starkly from current policy. COA 2 maintains the NCG as a consultation mechanism but does not follow through on deliberately integrating the ROK into nuclear planning or execution as intended in the Washington Declaration. Thus, ROK faith in U.S. commitment through consultation is likely delicate while faith by integration is virtually non-existent. Introducing either a U.S. DCA capability or a newly-developed nuclear IRBM to the ROK significantly increases both the perceived and actual U.S. military presence in South Korea which certainly boosts faith in U.S. assurance. Regarding the balance of fear, however, the risk that COA 2 establishes a security dilemma with North Korea and China is significant. First, both Chinese and North Korean capability expansion is derived from a substantial relative power differential to the U.S.. China’s widely published “10-dash line” illustrates how it derives its security from territorial expansion. North Korea has demonstrated its primary interest is regime survival and its nuclear program acquisition increases the credibility of its deterrent threat by expanding its relative power. COA 2 significantly enlarges U.S. relative power and interest in the INDOPACOM region which builds deterrent credibility, but it also directly threatens Chinese and North Korean keys to security thus creating a security dilemma. Because it marks a stark shift in nuclear deterrence policy, COA 2 likely faces considerable U.S. political backlash. Conversely, the ROK polity likely embraces COA 2 as its population’s call for the return of U.S. nuclear weapons to the Korean Peninsula reflect a desire for a nuclear-centric U.S. strategy. COA 2 incurs a substantial cost to the U.S. through either establishing an F-35 DCA squadron, developing and fielding a new nuclear IRBM, or both.

COA 3 achieves a consultation mechanism through the NCG similarly to COA 1 but bolsters the process by executing exchange diplomacy that targets understanding U.S. nuclear deterrence and assurance strategy. NCG effectiveness remains tied to White House politics, but exchange diplomacy provides an alternate means of consultation. COA 3 builds assurance faith through nuclear integration by incorporating the ROK military into nuclear planning and execution for CSNO. Furthermore, COA 3 empowers the ROK to take part in nuclear mission execution by creating a South Korean DCA capability. Although the U.S. will not store the nuclear weapons on the peninsula, this COA facilitates South Korea to possess a nuclear weapon capability for the first time in its history. This U.S.-enabled nuclear option will demonstrate U.S. trust and will provide the ROK with a capability in-line with NATO ultimately securing long-term South Korean faith in the U.S.. COA 3 neither expands nor shrinks the permanent U.S. military presence on the peninsula and therefore will not impact South Korean faith. Regarding deterrence, COA 3 maintains a stable balance of fear with China and North Korea. By storing the nuclear weapons elsewhere in theater, the U.S. keeps its relative power increase minimal while simultaneously messaging resolve to defend its allies and interests in INDOPACOM. Additionally, it provides an additional escalation step to deter mounting aggression – transporting the B-61s to the ROK. While refocusing on a nuclear-centric deterrence model will likely receive U.S. political backlash, a 2023 non-partisan report by the U.S. Congressional Strategic Posture Commission highlighted the need to substantially expand the U.S. nuclear posture to deter 21st Century aggression. In addition, since COA 3’s initiatives also have historical precedent in NATO, U.S. decision-makers are likely to accept COA 3 as viable. Likewise, COA 3’s empowerment mechanisms and economic incentives will garner the ROK polity’s support. Finally, COA 3 does produce a larger economic cost through economic incentives to South Korea, training and certification costs for the DCA unit, and construction of an in-theater nuclear storage facility with any additional supporting infrastructure.

COA Comparison

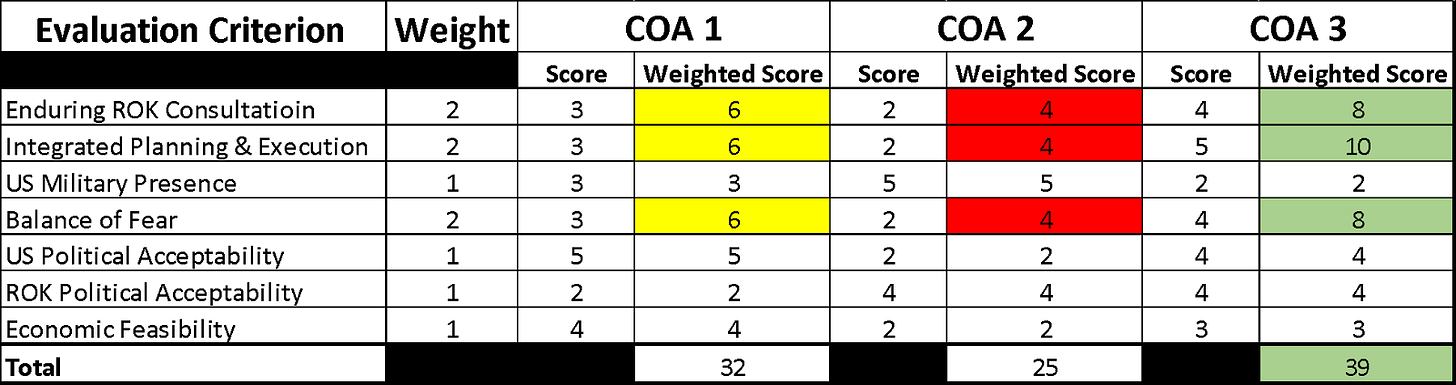

The following COA comparison table was developed using the evaluation criteria derived from Chapter 3 and the COA Analysis. Each evaluation category was assigned a weight metric, a 1 or a 2, based on its analyzed impact to either building faith or balancing fear on the Korean Peninsula. Each category was given a score from 1 to 5 then multiplied by the weight metric to determine its weighted score. Finally, each weighted score was added to produce the total score for each COA. The higher a COA scored, the more effective.

Based on the result, COA 3 is the most viable option to cultivate ROK faith in U.S. nuclear extended deterrence commitments while simultaneously balancing Chinese and North Korean fears. COA 1 is also viable, but several factors place it behind COA 3. First, the addition of targeted exchange diplomacy in COA 3 provides an additional means of consultation through U.S. deterrence strategy education. Second, introducing nuclear-capable DCA to the ROK Air Force enables South Koreans to fully engage in nuclear planning, training, and execution while also providing ROK citizens tangible evidence of U.S. nuclear assurance. COA 1 includes ROK integration via CSNO, but establishing organic DCA under COA 3 displays far greater U.S. trust in its ally yielding stronger long-term assurance. Finally, while COA 1 does little to boost the deterrence posture toward mounting regional threats, COA 3’s establishment of a ROK DCA capability demonstrates clear unified resolve from both allies without significantly increasing the security threat to North Korea or China thus avoiding security dilemma.

Conclusion

During the Cold War, the United States built alliances and coalitions to both deter Soviet nuclear aggression and prevent nuclear proliferation through its extended nuclear deterrence umbrella. Today, the U.S. faces a resurgent nuclear threat from Russia, China, and North Korea which threatens not only its national security but the security of the free world, and once again the U.S. nuclear umbrella remains key to defending freedom and democracy. While NATO demonstrated unity and confidence in the face of Russia’s unprecedented invasion of Ukraine, and even expanded to include Finland and Sweden, U.S. alliances in the Pacific languish under the growing threats from China and North Korea. South Korean public opinion polls reflect a serious desire for U.S. nuclear weapons to return to the peninsula or that the ROK pursue its own nuclear weapon program to feel protected from these threats. The fact that these views were echoed by ROK President Yoon in 2023 indicate that a U.S. assurance problem does exist in South Korea and timely U.S. action is needed to regain its ally’s confidence.

To develop appropriate courses of action, this paper delved into the concept of credibility, how it is calculated, the impact of emotional factors on credibility, how a nation builds credibility, and why nuclear proliferation is not a simple answer as some South Koreans seem to believe. The chief finding from this research is that deterrence and assurance are related but distinct strategic concepts requiring unique strategies to achieve the desired emotional outcome. Through successful deterrence, a nuclear actor instills fear in the mind of an opponent, but through successful assurance, a nuclear actor instills faith in the mind of an ally. To achieve assurance, an ally must believe that their nuclear patron will follow-through on its commitment to defend them, and while words are important, actions speak louder. At the same time, the U.S. must tread carefully when cultivating an adversary’s fear as too much may force that opponent into a security dilemma resulting in preemptive war.

To assure the ROK, the U.S. must execute a strategy dedicated to building South Korean faith in the U.S. nuclear umbrella. First, the U.S. must establish an enduring consultation mechanism for South Korean decision-makers to influence nuclear deterrence policy in the Pacific. Second, the U.S. must integrate the ROK military into the nuclear planning and execution process through information sharing, training, and bi-lateral exercises. Third, U.S. military presence on the peninsula remains a critical factor to both deterrence and assurance credibility by demonstrating U.S. interests at stake in Korea. COA 3 proved the best option because it most closely aligned with these mechanisms of faith-building while also minimizing the risk of inadvertent escalation caused by a security dilemma. In conclusion, the United States must strengthen its assurance with South Korea to protect its alliance and reduce the risk of South Korean nuclear proliferation. Additionally, U.S. must preserve regional stability by maintaining the balance of fear within its opponents. While the courses of action included in this paper are not all-inclusive, COA 3 most effectively builds faith with the ROK through consultation, integration, and military presence, and bolsters deterrent fear without substantially increasing the security threat to regional opponents. In the 21st Century, the United States is the biggest threat to nuclear proliferation. If states are not assured, they are forced to pursue security on their own. To ensure a Pacific safe for democracy, the United States must build faith and balance fear on the Korean Peninsula.

About the Author

Major Trapani graduated from the U.S. Air Force Academy in 2011 majoring in Foreign Area Studies and minoring in the Russian language. Upon graduation, he completed undergraduate pilot training and became a UH-1N Huey pilot. He has served as a Huey pilot in Yokota Air Base, Japan, Malmstrom Air Force Base, Montana, and F. E. Warren Air Force Base, Wyoming. In 2024, Major Trapani graduated with distinction from the U.S. Air Command and Staff College in the School of Advanced Nuclear Deterrence Studies (SANDS). He is currently serving as an Employment Strategist in the Operations Directorate at United States Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM) headquartered at Offutt Air Force4 Base, Nebraska.