A Brief Review of Economic Warfare Over Ukraine and its Application to a Taiwan Crisis: Lessons Learned and Opportunities for Deterrence

By Lieutenant Commander Phoenix Geimer, U.S. Navy

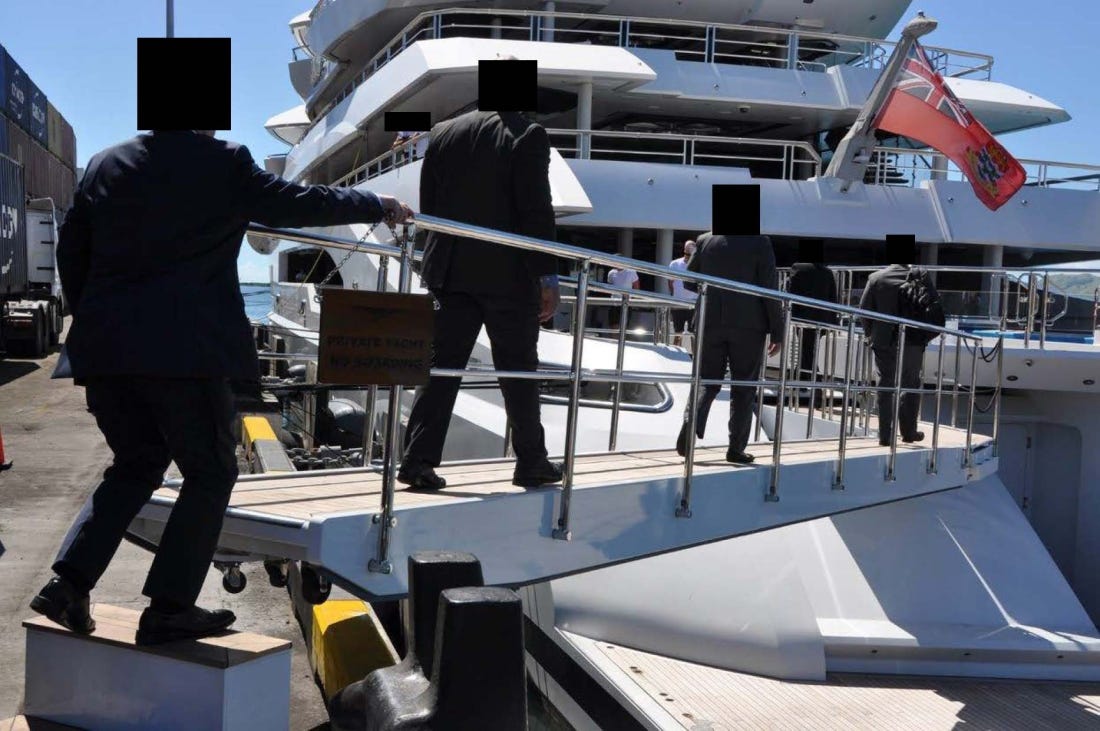

Photo: $300 Million Yacht Amadea of Sanctioned Russian Oligarch Suleiman Kerimov Seized by Fiji at Request of the United States on Grounds of Sanctions Evasion and Money Laundering. Department of Justice File Photo updated 06 February, 2025

Editor's Note: Because of space issues, LCDR Geimer's article is published here without research notes. The Journal is pleased to bring you this outstanding scholarship written by LCDR Geimer under the under the direction of Colonel Stéphan Samaran, Directeur du domaine "Stratégies, normes et doctrines" Institut de Recherche Stratégique de l'Ecole Militaire (Institute for Strategic Research - IRSEM)

Disclaimer: This document reflects solely the views of the author and does not represent the views of the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This article was originally written in French as part of the author’s BAC+8 postgraduate program at the Ecole de Guerre in Paris, France. This version is abridged, edited, and translated from the original to meet publishing requirements.

Economic attacks in the Russo-Ukrainian war began well before the invasion of February 24, 2022, and continue to this day. Although the war in Ukraine is still ongoing, the use of existing and novel economic weapons during the war in Ukraine has already credibly increased the perception of risks to China and the CCP compared to that which existed prior to February of 2022.

During the pre-war period, financial markets started anticipating the possibility of war months before Russia moved military equipment across the border. World leaders warned of potential sanctions, and even started levying them before the formal start of the war. Global commodity prices, including food, energy, and key materials, fluctuated wildly. Russia threatened to spark an economic crisis in Ukraine just by menacing military action.

As pressure built, it became clear that one of Russia’s most insidious options would be to coerce concessions from Ukraine and the west in exchange for reducing tensions that she herself created. Indeed, it seemed like that would likely occur. Western leaders fretted about the potential consequences of war, and seemed to encourage conciliation, even if it meant appeasing Putin.

Following the invasion, attempts by all parties in the conflict to insulate their economies from the effects of war while undermining their opponents economies, and therefore political will and military capacity, quickly reached unprecedented levels in a globalized economic environment. The level of innovation with economic weapons has been particularly important during this war, as economic warfare is seen as less escalatory than conventional warfare between nuclear armed states. Fuel and food pricing and exports were used as economic and political cudgels, the personal fortunes of oligarchs were targeted, materials shortages and sanctions disturbed global manufacturing and Russian military supply chains, novel financial attacks were undertaken, and Russia has had to confront a newly diminished economic reality.

The parallels between Ukraine and Taiwan are unmistakable. Both are liberal democratic countries, menaced by nuclear armed authoritarian neighbors with large militaries who demand unification based on their respective historical interpretations. Moreover, both Ukraine and Taiwan have common cultural roots and asymmetric economic relationships with the countries that menace them[1].

However, Russia isn’t China, and Ukraine isn’t Taiwan. While the Russian declarations of Ukraine not being a “real country[2]” may be openly ridiculed as ungrounded in reality, Taiwan’s status is much less clear - she is only officially recognized as a country by 14 nations.[3] Although Taiwan was recognized as a country by the United Nations from 1949 to 1971[4], she is currently not in the UN and is classified as only a territory. Even Taiwan’s largest guarantor of security, the United States, doesn’t formally recognize her as a sovereign nation. Finally, they have extremely different geography: Ukraine has managed to keep land and air lines of communication open during the invasion, permitting resupply of armaments, outflow of refugees, and international trade. Taiwan is an island that could find itself durably isolated by sea and air in the event of a crisis. These differences, as well as the American policy of “strategic ambiguity”, combine to make the impact and importance of some economic effects completely different between the two situations.

Furthermore, relative economic sizes and market positions means that a war over Taiwan would have profoundly more impact over the rest of the world, and in a non-linear manner. China has more ability to flex its market position in several key economic components, while Taiwan benefits from a “silicon shield”, wherein China and much of the world remain dependent on Taiwanese semiconductors for their own economic growth.

In a similar manner to Ukraine, opening salvos of economic warfare have already started over Taiwan, with predictions of an attempted annexation of Taiwan possible before the end of Xi Jinping’s current term in 2027. Apart from direct economic pressure on other nations, China has made a number of economic changes following the Ukraine war to protect her economy from the evolving and increasingly credible economic weapons used there. Western nations have meanwhile started to better prepare their economies for a potential Taiwan crisis while undermining China’s resilience from consequences.

Regardless of the threat of open war over Taiwan, an armed conflict is not necessary to precipitate a full Taiwan crisis or open economic warfare. Since China’s economy relies on being the world’s workshop, and the destructive and isolative effects of open war present substantially more important risks than purely economic, the author will focus primarily on scenarios that are economically relevant short of open war over Taiwan and could impose constraints or restraints on a response.

The author will analyze economic warfare areas where there has been a particularly strong impact during the war over Ukraine, as well as areas where there has been important innovation, in order to estimate whether those economic tools would retain their utility during a war over Taiwan. From there, asymmetric risks will be estimated, with economic impacts likely to influence military planning being highlighted. Finally, immediate and intermediate deterrent actions will be proposed.

Food Security

The use of food as an element of warfare has existed since prehistoric times, with biblical references[5] to salting the fields of conquered cities, and Egyptian depictions of siege[6] warfare dating from the 30th century BC. The modern globalized economic system has allowed food warfare to evolve beyond a tactic to create food insecurity and reduce an opponent’s ability to wage war directly, and into a military tactic designed to inflict economic harm to the target nation and generate political pressure internally and from third party nations[7].

When Russia attacked Ukraine, she severely reduced Ukraine’s ability to produce and export grain and food oil products via the Black Sea. Ports on the Black Sea were functionally closed to merchant traffic by defensive mining, blockades, and seizure. Large swaths of farmland in Ukraine was rendered unfarmable due to nearby violence, leading to crop wastage or reduction in agricultural activity. This blockage of food flow led to a disruption of the global food markets, with reduced inventory and increased prices leading to a risk of famine in countries far beyond the borders of the conflict area.

As both countries in that war are net exporters of food, these disruptions weren’t designed to create food insecurity within the conflict zone. Instead, the objective was to disrupt the Ukrainian economy, which relies heavily on food exports, as well as to create international pressure to resolve the conflict quickly, and likely to the benefit of Russia, so that food shipments could resume.

A similar disruption in food flow during conflict over Taiwan would likely have inverse impacts, as those countries are both net importers of food. Economic pressure on food exporting countries who may wish to retain their share of the import markets would be quickly translated into political pressure, reducing the will of major food exporting countries to intervene in the conflict.

Countries who export agricultural products risk a degree of economic disruption directly related to their level of economic dependence on China. New Zealand, for example, meat exports to China represent nearly 6% of their GDP. For the United States, their agricultural exports to China represent 33 billion dollars annually[8]. The risks of this type of economic warfare are far from hypothetical.

Indeed, China has frequently used its dominant position in global food markets to respond economically to political positions she doesn't like, such as rejections of Australian wine imports[9] in response to wider political tensions with Canberra, limitations on US soybean purchases in the mid 2010s, and restrictions on Taiwanese food and alcohol imports[10] in 2022.

China doesn’t risk famine in any scenario examined, but she could potentially impose famine conditions in Taiwan within short time periods. Taiwan is extremely vulnerable to food insecurity in the event of this conflict. Taiwan only produces about 40%[11] of their food calories domestically, and relies on trade for food imports. If China were to isolate Taiwan, Taiwan would rapidly exhaust their food reserves. While exact volumes of Taiwan’s food supplies aren’t published, they are estimated to only be sufficient for a few weeks for most products[12]. This short time frame would impose substantial pressure on a response to a Taiwan crisis.

Taiwan should decrease their vulnerability to this strategy by creating a national reserve policy of food products upon which they’re import dependent. Taiwanese families should be encouraged to stockpile enough non-perishable foods to get them through a prolonged period of isolation.

Currency and Finances

Economic pressure from financial warfare has major effects that don’t wait for open hostilities or even sanctions initiation to start taking effect. For example, it’s estimated that a 10 Ruble gain in the USD exchange rate for a year can destroy 1.2%[13] of Russia’s GDP, and pre-war anticipation of sanctions or war can create disruptions in foreign exchange markets in direct relation to their perceived credibility.

From the day after the invasion when Russia closed their bourse, until now in early 2025, Russia has only been able to partially open their stock market due to increasingly restrictive sanctions. Western sanctions aimed to attack Russia's access to capital markets, increase borrowing costs for the sanctioned Russian-owned financial institutions, and progressively erode the country's industrial base; as well as block Russia's foreign exchange reserves and prevent key Russian banks from conducting fast and efficient financial transactions globally[14].

Novel financial sanctions included the national Central Bank of Russia ‘asset freeze’, which seems to have taken Russian officials by surprise. Such coordinated action against a central bank was, in fact, unprecedented wherein it prohibits the Central Bank of Russia from accessing its assets and reserves stored in central banks and private institutions in the EU, USA, UK and other Western allies[15].

It is estimated that more than half[16] of Russia’s 600 billion USD in reserves are frozen, potentially affecting both the stability of the country's currency exchange rate and the ability to use foreign assets to provide funds to Russian banks in an attempt to limit the effect of other sanctions, while the remainder is projected to be exhausted by 2027.

One of the most important and controversial financial measures relates to the decision to impose a selective ban on Russian financial institutions from SWIFT, the vast network used by over 11,000 institutions[17] to send and receive information and instructions about financial transactions. The reason for a selective instead of total ban was due to the continued European reliance on Russian energy.

Despite a lack of clear signaling before the war, the sanctions have been much more strict than projected. With overlapping sanctions impacting the function of the market, most financial services companies made it clear that they intended to sell all positions in Russian companies and divest from the Russian market entirely. Russian authorities, with this sword of Damocles over their heads, have likely evaluated that the ‘sell at any price’ intent of most western firms could potentially lead to a contagion effect which could cause a prolonged Russian market collapse.

The Russian central bank’s extreme reaction to mitigate a potential financial collapse is a clear indicator that they view the sanctions as potentially devastating, but the contradicting messaging pre-war of the potency and credibility of the sanctions mitigated much of their potential deterrent effects, while allowing Russia to defer a portion of their impact.

Before a possible war over Taiwan, a similar story could unfold. Even as pressure rises, and despite possible efforts by various leaders to calm their respective markets, stock prices and debt costs will start to reflect the risks of war and sanctions for all potential parties to the conflict. However, there are likely to be a few key differences.

The pre-war period for Taiwan, so clearly important in deterrence, is likely to look quite different than the lead-up to war in Ukraine due to the increased credibility and unprecedented potency of western sanctions demonstrated there. China, also, might learn from the possibility that Russia could have converted their pre-war military and economic leverage into progressive concessions without the necessity of committing troops and provoking a stronger international reaction.

For structural reasons, China is particularly vulnerable to the types of foreign sanctions enacted against Russia. Unlike Russia, China depends on access to debt markets to sustain its economy, and a default would have orders of magnitude more impact on the Chinese population and global economy.

To mitigate risk of these reserves being frozen, China has shifted over 45 billion of its treasury holdings to offshore jurisdictions since the start February of 2022[18], with another half a trillion in US treasury and corporate debt estimated to be cached in an opaque web of offshore accounts[19]. With such a buffer at their disposal, the Chinese central bank has essentially built a moderate insurance policy against economic shocks caused by sanctions that have been deployed in Ukraine.

China has also taken action to insulate themselves from the effects of a SWIFT cutoff. In 2015, China had launched its own parallel financial system, CIPS (China International Payments System), a payment network that already counts over 1,600 banks as users[20]. China has also launched a digital Yuan payment settlement system for domestic transactions, which is capable of partially replacing credit card payment networks.

However, China also has unique financial vulnerabilities, such as the opaque Chinese local government debt market, or Chengtouzhai. Through this system, local governments use land as collateral to issue debt to fund infrastructure development and operations. The solvency of these loans is directly linked to the value and stability of Chinese real estate, but the Chinese system facilitates land hoarding by local governments, encouraging speculative bubbles[21].The fragility of this market means that a sharp increase in the Central Bank rate, or a moderate decrease in Chinese property values, could each collapse it. The implosion of this market could have the dual effect of decimating Chinese property values and idling a huge number of the 53 million people employed by the construction industry in China[22], with follow-on effects for the rest of their economy.

This market is particularly at risk of implosion on the eve of war, as investors flee to safer investments in times of uncertainty and liquidity becomes scarce. Reinforcing these tendencies via targeted sanctions could be seen as a reasonable reaction to a series of initial provocations aimed at conquering Taiwan, with the potential for a strong asymmetric impact on China.

In addition to the other sanctions deployed in Ukraine, clear communication now of potential sanctions on this sector, before a threat of war is priced into the market, would also have an effect of maximizing capital flight from China as a crisis precipitates, and increase the overall effectiveness of potential sanctions.

Energy

Russia benefited from a symbiotic relationship with Europe in the energy domain prior to the war in Ukraine. Energy exports represent about 20% of Russia’s GDP on average[23], indicating that Russia is highly dependent on access to the global energy market. Russia’s status as one of the largest global energy exporters, as well as her extensive pipeline network, created an environment where Europe became so reliant on deliveries of Russian gas and oil by pipeline, that they would struggle to completely replace those shipments by other methods if they were interrupted. Russia has also underinvested in the necessary infrastructure to export oil and gas via seaports, making it reliant on Europe to consume a large portion of their production.

Although it wasn’t evident at the time, Russia started squeezing the European energy market six months before February of 2022. In their preparatory phase of economic warfare, pipeline deliveries from Russia declined by 25% year-on-year in Q4 2021[24]. This decrease in Russian pipeline supply to the EU became more pronounced in the first seven weeks of 2022, falling by 37% year-on-year[25]. As a consequence of low inventory levels at the beginning of the heating season, and the sharp decline of Russian piped flows to the EU, gas storage levels fell to 30% below their working storage capacity[26], with Russian owned Gazprom storages accounting for half of the EU’s storage deficit[27].

Russia has demonstrated willingness to take advantage of this relationship leading up to and throughout the war by punishing countries whose actions they disprove of with reduced deliveries of energy, generating an asymmetric political advantage in Russia’s favor. It’s likely that this perception of asymmetric leverage weighed into war planning at their strategic level.

To restrict Russian energy profits, while assuring energy flows, the G7 implemented a novel price cap mechanism on Russian energy products. This type of sanction has never previously been tried, but indications are that Russian energy products are continuing to reach the global market, and are largely being sold well under the cap[28] or with a substantial risk premium to spot prices when transported via the “shadow fleet”. Cumulative Russian energy export revenues have fallen 50% from their March 2022 peak[29] and the IEA estimates that Russia will ultimately lose out on about a trillion USD in revenue this decade due to permanent energy demand reallocation by their customers, or about 7% of their projected annual GDP in that period[30].

China has a different relationship with the global energy market than Russia, as China is dependent on energy imports. However, similarly to their relation to the global food market, their purchasing power has the ability to disturb global energy markets, and makes it unlikely that their access to energy could be limited outside of a war. Also, similar to her food stockpiles, China maintains massive energy stockpiles with months of autonomy.

While China may be capable of enduring the effects of energy warfare for months, Taiwan is much more fragile. In 2021 Taiwan relied on imports of fossil fuels for 97.7 percent of its total energy supply[31]. Current Taiwanese energy stockpiles contain 39 days of coal, 146 days of oil, and 11 days of natural gas[32]. If China were to implement a full or even partial quarantine strategy, Taiwan could face blackouts and severe damage to its economy after just 11 days[33], since natural gas accounts for about 37 percent of electricity generation[34].

As all of Taiwan’s natural gas and oil import terminals are on its west coast, sustained sea zone closures in just the Taiwan Strait alone could have a rapid effect on Taiwan’s security. Due to Taiwan’s lack of domestic hydrocarbon resources, this strategy should be treated as highly provocative, and features as a primary risk during a quarantine scenario.

This, combined with other pressures, could force Taiwan to make concessions to China before any kinetic war occurred, and makes it increasingly likely that energy warfare would be a prominent feature of a possible war over Taiwan.

Asset Seizure and Forfeiture

Asset seizures from wealthy Russians overseas have played a dramatic role in the Russia-Ukraine war, with yachts, mansions, and even sports teams being seized from their oligarch owners. After the first six months of war, over 1,000 Russian individuals have been sanctioned, and over 30 billion USD of personal assets have been frozen and seized[35]. While sanctions against individuals isn’t a new technique, the major evolution of this period has been to not only freeze assets, as a temporary international police measure, but also seize them and permanently confiscate them, as part of judicial proceedings against the same targeted individuals[36].

Asset seizures hasn't been limited to personal assets and individuals, but have also included overseas assets owned by Russian companies, such as Gazprom storage facilities in Germany and the Baltics. Western countries are simultaneously at various stages of developing a legal framework to convert seized assets into reparations for the war in Ukraine, while the search and seizure of assets continues.

This evolution has measurably increased the political pressure in the Kremlin’s elite ranks. Although sordid, the rate of mysterious deaths/assassinations of extremely wealthy Russian oligarchs deemed political problems can be useful to qualitatively evaluate the level of political tension within the Russian elite, with the assumption that these deaths are used to both neutralize problems and terrorize others into staying in line. With a near quadrupling of the annual oligarch suspicious death rate following the decision to invade Ukraine, a sharp rise in elite internal tension seems to have occurred, and could leave Russia at increased risk of a coup d’etat or insurrection.

China has similar vulnerabilities to these types of sanctions and has been working proactively to reduce her risks. Chinese enterprises and individuals hold trillions of dollars in physical assets overseas that would be vulnerable to seizure and forfeiture.

For the last decade, buying overseas real-estate has been a popular method for wealthy Chinese people to cache money outside of China. Although global figures don’t exist, the global Chinese ownership of overseas property is at least 3 trillion USD, but is potentially trillions higher[37][38]. Many of these overseas investments are similarly held by shell companies held offshore.

To reduce these risks and insulate the CCP from coercive sanctions against individuals, starting in May of 2022, the party’s Central Organization Authority implemented a new policy prohibiting spouses and children of ministerial-level officials from holding — directly or indirectly — any real estate abroad or shares in entities registered overseas. This appears to be a direct acknowledgment of the effectiveness of this innovative economic weapon and that this type of economic pressure is perceived as a serious risk to party legitimacy and autonomy if there were to be a crisis over Taiwan.

Chinese companies also hold a significant amount of overseas property. Most prominent of these assets are the 4 trillion USD (as of 2020) of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects[39]. Cumulatively, China’s overseas assets are a similar size to their GDP, and threatening their seizure would present an asymmetric attack against China, impacting both their citizens and enterprises.

Western leaders could magnify this perceived risk by making it clear now that Chinese politicians and oligarchs would have a lot to personally lose in the event of a Taiwan crisis. Updates to banking secrecy laws unveiling beneficial owners of large assets would be necessary to further enhance sanction effectiveness in the event of a war over Taiwan (or anywhere else).

Key Materials

Disruptions caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the ensuing economic sanctions on Russia, and its potential retaliation have severely affected global markets. Prices of oil, gas and certain agricultural products have risen, and uncertainty also struck markets in relation to metals and minerals that are produced in Russia and which are indispensable to supply chains of modern manufacturing production. Aluminum, nickel, titanium, palladium, vanadium, and potash are among those raw materials most impacted by the supply disruption[40]. Put simply, the direct effects of the war have made it more difficult for producers to deliver materials that are critical to the global manufacturing system.

Sanctions on semiconductors and other products in place since the Russian annexation of Crimea, and strengthened following the invasion of Ukraine, have severely restricted Russia’s ability to build new supplies of modern weapons and repair existing equipment. The military impact has been insidious.

Supplying the Russian military industry has forced Russia to adopt a war economy, which has skewed her labor force towards military production. Despite this, new production alone hasn’t been able to keep up with the rates of losses in Ukraine[41]. The Russian military retains massive stores of arms and ammunitions. Russia has already refurbished about 4,000 mothballed main battle tanks and retains roughly an equal number in storage[42], which would still be a force almost as numerous as all of the armies in Europe combined[43]. Clearly, economic pressure alone hasn’t been enough to completely stop the inertia of the Russian military industrial complex.

In a war over Taiwan, the flow of key materials, such as lithium and semiconductors, is likely to play a similar role, but magnified by the relative importance of their economies to global production.

With regards to lithium, China is both the world's largest consumer, and world’s largest producer of lithium batteries. During a Taiwan crisis, disruption of the flow of lithium through China could be used as an economic weapon by either China or the west. However, this form of economic squeeze would clearly be lose-lose. Western nations should prepare for this risk by developing key material sources, refining, and production operations outside of China.

With semiconductors, unlike with lithium, the economic harm would be much more asymmetric. Just one Taiwanese company, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), produces 64% of all the world’s semiconductors[44]. The loss of Taiwan’s production would create incalculable damage to the global economy, not just to China.

The concept that neither China nor the west can thrive without Taiwanese semiconductors is called the “silicon shield”. It essentially means that China would do great self-harm by isolation of Taiwan, and western countries would have a major incentive to protect Taiwan’s industry.

A recent series of legislation in the United States seems to acknowledge and seek to mitigate the risks presented in the semiconductor and lithium industries. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act creates incentives for the refining and production of lithium batteries in the USA[45], while the 2022 CHIPS Act provides investment funds and incentives for semiconductor manufacturers to increase their production in the USA[46]. On top of that, the Biden administration released a massive series of sanctions against China’s semiconductor industry in October of 2022[47]. Collectively, these actions should reduce China’s economic leverage over the west, increase China’s critical dependence on Taiwan in the status-quo, and help insulate the global economy from the potential economic shock of a Taiwan crisis.

Of course, protection of an industry isn’t the same as protection of a country, so there remains a major risk that western leaders might choose to urge Taiwanese leaders to bend to Chinese pressure and accept concessions during a coercive crisis. Instead, western leaders should use every tool available to ensure that the silicon shield remains effective. During a Taiwan crisis, purely economic weapons should be used to start to deplete Chinese semiconductor stockpiles, as well as partially disable the Chinese domestic semiconductor industry, by sanctioning a large number of the required global inputs. This would increase China’s reliance on an intact Taiwan.

Economic interdependence is often reciprocal with key materials. Western countries should continue to develop policies that nurture production of critical materials in friendly nations in order to limit the economic leverage China would have in a war over Taiwan, while publicly assuring that China would never benefit from Taiwan’s industries.

Cumulative Impacts and Risks

Russia has lost between 3.5%[48]. and 16%[49][50] of her GDP since she invaded Ukraine. Due to deliberate concealment of economic data by Russia, it’s not possible to know exactly where in this range the truth lies, but it nevertheless reflects bleaker future economic prospects for Russians since the war started.

The war in Ukraine is estimated to have removed about 1% of global GDP growth, and added about 2% to global inflation[51], while a war over Taiwan is predicted to destroy 15-25% of global GDP[52]. Those costs aren’t spread evenly - they disproportionately harm the parties directly involved.

Russians seem to take pride in their ability to suffer worse than their adversary and their leaders haven’t suffered major political risks from the economic decline. However, the priority of the Chinese Communist Party is to guarantee and strengthen its political power. The best way to do this has continuously been to guarantee a minimum quality of life and to improve the living conditions of the population[53]. When this guarantee is questioned, such as by declining standards of living, the power and legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party is weakened.

Since a major economic drop related to a Taiwan crisis would present substantial political risks to Chinese leaders, the CCP might use more deniable methods to exert hegemony over Taiwan to reduce economic impacts of her revanchism.

China has already demonstrated capability to use various gray zone methods, such as cyber attacks on key infrastructure and deploying their maritime militia to obstruct maritime traffic and law enforcement. With the options available and Taiwan’s relative fragility to these actions, the provocative act of using the People’s Liberation Army-Navy (PLA-N) to enforce a declared quarantine might even be more provocative than necessary to put extreme pressure on Taiwan. China is more likely to undertake gray zone tactics if she sees asymmetric leverage, such as the ability to impose severe food or energy shortages, or to avoid triggering damaging sanctions.

A lesson learned from the war in Ukraine is the importance of preventing gray zone activity from escalating into a threat. The first step to prevent escalation of gray zone operations is to focus on thwarting them and to draw clear lines about attribution[54] to impose costs and risks on the aggressor.

As was shown in the lead-up to the war in Ukraine, coercive pressure can be used as an economic and political weapon, and can be internal and external. China could start a crisis that falls short of risking open war, but still results in increasing domestic and international pressure on Taiwan to make concessions to China in order to find a solution. Taiwan risks quickly finding herself ceding varying levels of sovereignty without open war breaking out.

Conclusions

After considering various aspects of the economic war over Ukraine, it’s evident that western nations have a large variety of tools available to influence China that are asymmetric and palatable to use as tensions rise, but they should also prepare to defend against economic attacks.

When viewed through an economic lens, it appears that the highest risk scenario would be for China to attempt conquest of Taiwan by taking initial actions that aim to bring Taiwan into increasing degrees of hegemony and de-facto control while minimizing sanctions. This could appear as a series of smaller incursions, or gray zone actions, taken over many years that slowly nibble at pieces of Taiwan’s autonomy, but doesn’t exclude the possibility of a later invasion.

Economic attacks often require longer time frames for their impacts to be perceived, so effective crisis planning measures must create the necessary buffers of time required for economic impacts to become meaningful and deny a potential fait accompli to China.

Since Taiwan’s most immediate risk during any crisis scenario is her access to food and energy, it is vital that she take steps now to reduce or mitigate the potential effects of actions which could isolate her, as well as increase her ability to identify and attribute potential isolating events. To reduce these risks, Taiwan should:

1. Immediately pursue a strategy of generating her own energy without reliance on hydrocarbon imports, such as by solar, wind, nuclear, and/or geothermal production.

2. Build and maintain stockpiles of food and necessary hydrocarbons that are capable of providing months of resilience to isolation.

3. Ensure that military exercises between Taiwan and allied nations address gray zone and quarantine operations that could isolate Taiwan, while enabling ongoing fusion of intelligence on Chinese gray zone activities to provide clear attribution to China.

Western leaders should be sensitive to coercive actions and be prepared to enact economic penalties at sufficiently low thresholds early in the lead up to a potential conflict to maximize their deterrent and punitive effects. They should also anticipate coercive economic tactics by China to prevent interference or enforce acceptance of her actions. To maximize deterrence, reduce the risks on their own economies, and maximize perception of risk by the CCP, western nations should:

1. Develop competitive western producers in key industries, such as lithium batteries and semiconductors, while denying China the ability to dominate those markets.

2. Demonstrate an intent to inflict the maximum harm possible on the Chinese economy if China attempts a conquest by stating clearly and consistently that any actions which undermine the independence of Taiwan, will have a strong response.

3. Adopt legal frameworks to identify where and how wealthy Chinese individuals, enterprises, and government components cache their assets abroad in order to hold those assets at a more credible risk in the event of a conflict.

4. Develop strategies to mitigate and respond to economic coercion, including strategies to assist smaller nations to resist economic coercion and protect their own economic interests.

While war is ultimately a political decision, as long as Chinese leaders perceive the economic impacts and associated political risks of Taiwan conquest to be greater challenges to their legitimacy than failing to act on Taiwan, economic warfare will continue to have a deterrent effect against an attempted takeover of Taiwan.

About the Author

Lieutenant Commander Phoenix Geimer is an active duty Foreign Area Officer in the U.S. Navy and a former Naval Flight Officer on the EP-3E aircraft. He is currently serving as the U.S. Naval Attaché in Algiers, Algeria.

End Notes

[1] Chang CC, Yang AH. Weaponized Interdependence: China's Economic Statecraft and Social Penetration against Taiwan. Orbis. 2020;64(2):312-333. doi: 10.1016/j.orbis.2020.02.002. Epub 2020 Mar 4

[2] Baker, Sinéad. “Putin Denies Planning to Revive the Russian Empire after Declaring That Ukraine Is Not a Real Country and Sending Troops There.” Business Insider, Business Insider, https://www.businessinsider.com/putin-denies-reviving-russian-empire-says-ukraine-not-real-country-2022-2?r=US&IR=T. Consulted 01 February 2023.

[3] Yang, William. “Will Taiwan Lose Another Diplomatic Ally to China? – DW – 10/03/2022.” Dw.com, Deutsche Welle, 3 Oct.

[4] Countries That Recognize Taiwan 2023, https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/countries-that-recognize-taiwan. Consulted 01 February 2023.

[5] The book of Juges (9:45)

[6] Needham, Joseph, et al. “Part 6.” Science and Civilisation in China, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1984, p. 446.

[7] Strubenhoff, Heinz. “The War in Ukraine Triggered a Global Food Shortage.” Brookings, Brookings, 15 June 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2022/06/14/the-war-in-ukraine-triggered-a-global-food-shortage/. Consulted 26 October 2022

[8] “China 2021 Export Highlights.” USDA Foreign Agricultural Service

[9] Pickard, Christina. “Trade Dispute with China Puts Australian Wine Industry in a Precarious Position.” Wine Enthusiast, 9 Mar. 2022, https://www.winemag.com/2022/03/10/china-australia-wine-tariffs/. Consulted 01 February 2023.

[10] Hioe, Brian. “China Slaps Export Bans on Taiwanese Goods – Again.” – The Diplomat, For The Diplomat, 16 Dec. 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/12/china-slaps-export-bans-on-taiwanese-goods-again/. Consulted 01 February 2023.

[11] Andoko, Effendi, Et alii "Review of Taiwan’s food security strategy." FFTC agricultural policy platform. Taipei (2020).

[12] Person. “Taiwan Taking Monthly Energy, Food Inventories in Case of China Conflict.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 5 Oct. 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/taiwan-taking-monthly-energy-food-inventories-case-china-conflict-2022-10-05/. Consulted 26 October 2022.

[13] Demertzis, Maria, Et alii "How have sanctions impacted Russia". Policy Contribution 18 (2022) : 2022. https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/PC%2018%202022_1.pdf Consulted 30 December 2022.

[14] Mills, Claire. "Sanctions Against Russia." The House of Commons: Research Briefing (2022).

[15] Girardone, Claudia. "Russian sanctions and the banking sector." British Journal of Management (2022).

[16] Mills, Claire. "Sanctions Against Russia." The House of Commons: Research Briefing (2022).

[17] About Us.” SWIFT, https://www.swift.com/about-us. Consulted 11 November 2022.

[18] Evans, Brian. “China Shifts Us Bond Holdings Offshore, Potentially beyond the Reach of Any Future Currency Sanctions, Report Says.” Business Insider, Business Insider, Sept. 2022, https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/bonds/china-us-debt-treasury-holdings-currency-sanctions-bermuda-cayman-islands-2022-9. Consulted 11 November 2022.

[19] Coppola, Antonio, Et alii "Redrawing the map of global capital flows: The role of cross-border financing and tax havens." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 136.3 (2021): 1499-1556. Consulted 12 November 2022.

[20] CIPS.com.cn. CIPS Participants Announcement No. 104. 25 Jan 2025, https://www.cips.com.cn/en/2025-01/08/article_2025010809534519888.html Russian_alternatives_to_SWIFT/links/61fa86f14393577abe0875e8/Geoeconomic-infrastructures-Building-Chinese-Russian-alternatives-to-SWIFT.pdf. Consulted 27 December 2022.

[21] Zhang, J., Li, L., Yu, T., Gu, J., & Wen, H. (2021). Land assets, urban investment bonds, and local governments’ debt risk, China. International Journal of Strategic Property Management, 25(1), 65-75. https://doi.org/10.3846/ijspm.2020.13834 Consulted 11 November 2022.

[22] Zhang, Wenyi. “China: Number of Construction Employees.” Statista, 14 Dec. 2022, https://www.statista.com/statistics/279243/number-of-construction-employees-in-china/. Consulted 11 November 2022.

[23] Statista Research Department “Russia GDP Oil and Gas Percentage Quarterly 2022.” Statista, 16 Jan. 2023, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1322102/gdp-share-oil-gas-sector-russia/. Consulted 27 February 2023

[24] International Energy Agency. “Russian Supplies to Global Energy Markets – Analysis.” IEA, 2022, https://www.iea.org/reports/russian-supplies-to-global-energy-markets. Consulted 03 December 2022

[25] Idem.

[26] Idem.

[27] Idem.

[28] Simon Johnson and Catherine Wolfram. “STRENGTHENING ENFORCEMENT OF THE RUSSIAN OIL PRICE CAP.” Brookings Economic Studies, May 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/20240528_ES_Sanctions_JohnsonWolfram_Final.pdf Consulted 09 February 2025

[29] Russian Fossil Tracker “ Payments to Russia for fossil fuels since 24 February 2022” Russia Fossil Tracker, 09 Feb. 2025, Russia Fossil Tracker – Payments to Russia for fossil fuels since 24 February 2022

[30] “Russia GDP2022 Data - 2023 Forecast - 1988-2021 Historical - Chart - News.”

[31] Kucharski, Jeff. “Taiwan's Greatest Vulnerability Is Its Energy Supply.” – The Diplomat, For The Diplomat, 13 Sept. 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/09/taiwans-greatest-vulnerability-is-its-energy-supply/. Consulted 03 December 2022.

[32] “Management of Oil Security Stockpile.” 經濟部能源局(Bureau of Energy, Ministry of Economic Affairs, R.O.C.)全球資訊網, https://www.moeaboe.gov.tw/ECW/english/content/Content.aspx?menu_id=8675. Consulted 03 December 2022.

[33] Kucharski, Jeff. (13 Sept. 2022)

[34] Idem.

[35] Farivar, Masood. “US-Backed Task Force Seizes More than $30B of Russian Oligarch Assets.” VOA, Voice of America (VOA News), 29 June 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/us-backed-task-force-seizes-more-than-30-billion-worth-of-russian-oligarch-assets-/6638426.html. Consulted 25 December 2022.

[36] Daniel Ventura, L'avenir des sanctions ciblées et la recherche de la responsabilité individuelle : Les leçons tirées des forces opérationnelles " freeze and seize " des États-Unis et de l'Union européenne. La démocratie et ses ennemis - Conférence 2022 de la SocietàItaliana di Scienza Politica (SISP), Sep 2022, Rome, Italie.

[37] “Chinese Investors Have Spent $300 Billion on US Property, Study Finds.” CNBC, CNBC, 17 May 2016, https://www.cnbc.com/2016/05/16/chinese-investors-have-spent-300-billion-on-us-property-mbs-rosen-study-finds.html. Consulted 27 December 2022.

[38] Tostevin, Paul, and Mat Oakley. “The Total Value of Global Real Estate.” Savills Impacts, 7 Dec. 2021, https://www.savills.com/impacts/market-trends/the-total-value-of-global-real-estate.html. Consulted 27 December 2022.

[39] “China Belt and Road Projects Value Now Exceeds US$4 Trillion.” Silk Road Briefing, 16 Sept. 2021, https://www.silkroadbriefing.com/news/2020/11/25/china-belt-and-road-projects-value-now-exceeds-us4-trillion/. Consulted 27 December 2022.

[40] “The Supply of Critical Raw Materials Endangered by Russia's War on Ukraine.” OECD, https://www.oecd.org/ukraine-hub/policy-responses/the-supply-of-critical-raw-materials-endangered-by-russia-s-war-on-ukraine-e01ac7be/. Consulted 26 December 2022.

[41] ArmyInform. “УР дізналося плани і спроможності росії щодо модернізації та виробництва танків.” Vyacheslav Zhaivoronok, 16 Feb 2024, https://armyinform.com.ua/2024/02/16/gur-diznalosya-plany-i-spromozhnosti-rosiyi-shhodo-modernizacziyi-ta-vyrobnycztva-tankiv/. Consulted 09 Feb. 2025.

[42] forcesnews, “Thousands of tanks destroyed, with T-80 bearing the brunt of Russian losses in Ukraine.” Simon Newton, 23 Jan 2025 https://www.forcesnews.com/news/russia-losing-thousands-tanks-ukraine-and-one-particular-has-taken-huge-losses#:~:text=How%20many%20have%20they%20lost,Soviet%2Dera%20T%2D80. Consulted 09 February 2025.

[43] “Optimizing Europe's Main Battle Tank Capabilities.” European Defence Matters, https://eda.europa.eu/webzine/issue14/in-the-field/optimizing-europe-s-main-battle-tank-capabilities. Consulted 06 February 2023.

[44] “Global Semiconductor Foundry Market Share: By Quarter.” Counterpoint Research, 26 Nov 2024, https://www.counterpointresearch.com/global-semiconductor-foundry-market-share/. Consulted 09 Feb 2025.

[45] “Text - H.R.5376 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): Inflation Reduction Act ...” Congress.gov, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text.

[46] “S.3933 - Chips for America Act 116th Congress (2019-2020).” Congress.gov, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/3933/text.

[47] Kharpal, Arjun. “U.S. Sanctions on Chipmaker Smic Hit at the Very Heart of China's Tech Ambitions.” CNBC, CNBC, 28 Sept. 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/09/28/us-sanctions-against-chipmaker-smic-hit-china-tech-ambitions.html. Consulted 26 déc. 2022.

[48] “OECD Economic Outlook.” OECD, 22 Nov. 2022, https://www.oecd.org/economic-outlook/november-2022/. Consulted 31 déc. 2022.

[49] Andrey V. Zubarev & Mariya A. Kirillova, 2022."Estimation de la baisse du PIB de la Russie due aux restrictions commerciales avec l'UE, les États-Unis, la Grande-Bretagne et le Japon" (Оценка Потерь Ввп Из-За Ограничения Странами Ес, Сша, Великобританией И Японией То," Russian Economic Development, Gaidar Institute for Economic Policy, numéro 8, pages 21-23, août. https://ideas.repec.org/a/gai/recdev/r2267.html. Consulted 31 déc. 2022.

[50] Anna Pestova, Mikhail Mamonov, Steven Ongena (mars 2022), "Le prix de la guerre : Les effets macroéconomiques des sanctions de 2022 contre la Russie" https://voxeu.org/article/macroeconomic-effects-2022-sanctions-russie. Consulted 31 déc. 2022.

[51] Irtyshcheva, I., Kramarenko, I., & Sirenko, I. (2022). L'ÉCONOMIE DE GUERRE ET LE DÉVELOPPEMENT ÉCONOMIQUE D'APRÈS-GUERRE : WORLD AND UKRAINIAN REALITIES. Baltic Journal of Economic Studies, 8(2), 78-82. https://doi.org/10.30525/2256-0742/2022-8-2-78-82 Consulted 31 déc. 2022.

[52] McKinsey Global Institute, "La Chine et le monde : Inside the Dynamique d'une relation en mutation", juillet 2019, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/featured%20insights/china/china%20and%20the%20world%20inside%20the%20dynamics%20of%20a%20changing%20relationship/mgi-chine-et-le-monde-rapport-complet-juin-2019-vf.ashx. Consulted 31 déc. 2022.

[53] Brown, William N. "La 5e grande invention de la Chine". Chasing the Chinese Dream. Springer, Singapour, 2021. 119-126.

[54] Herdt, Courtney Stiles, and Matthew "BINCS" Zublic. “Baltic Conflict: Russia's Goal to Distract Nato?” CSIS, Center for Strategic and Internationa Studies, https://www.csis.org/analysis/baltic-conflict-russias-goal-distract-nato. Consulted 01 February 2023